During Frank Reich’s three decades as an NFL quarterback and coach, his Saturdays were for last-minute game preparation, travel or rest. The league was so consuming that he rarely, if ever, had time for much else.

“All my years in the NFL,” Reich said, “I barely watched college football at all.”

That gave Reich a somewhat outside perspective when the former Indianapolis Colts and Carolina Panthers head coach became Stanford’s interim coach in March. His conclusion: College football “feels a little bit NFL-ish.”

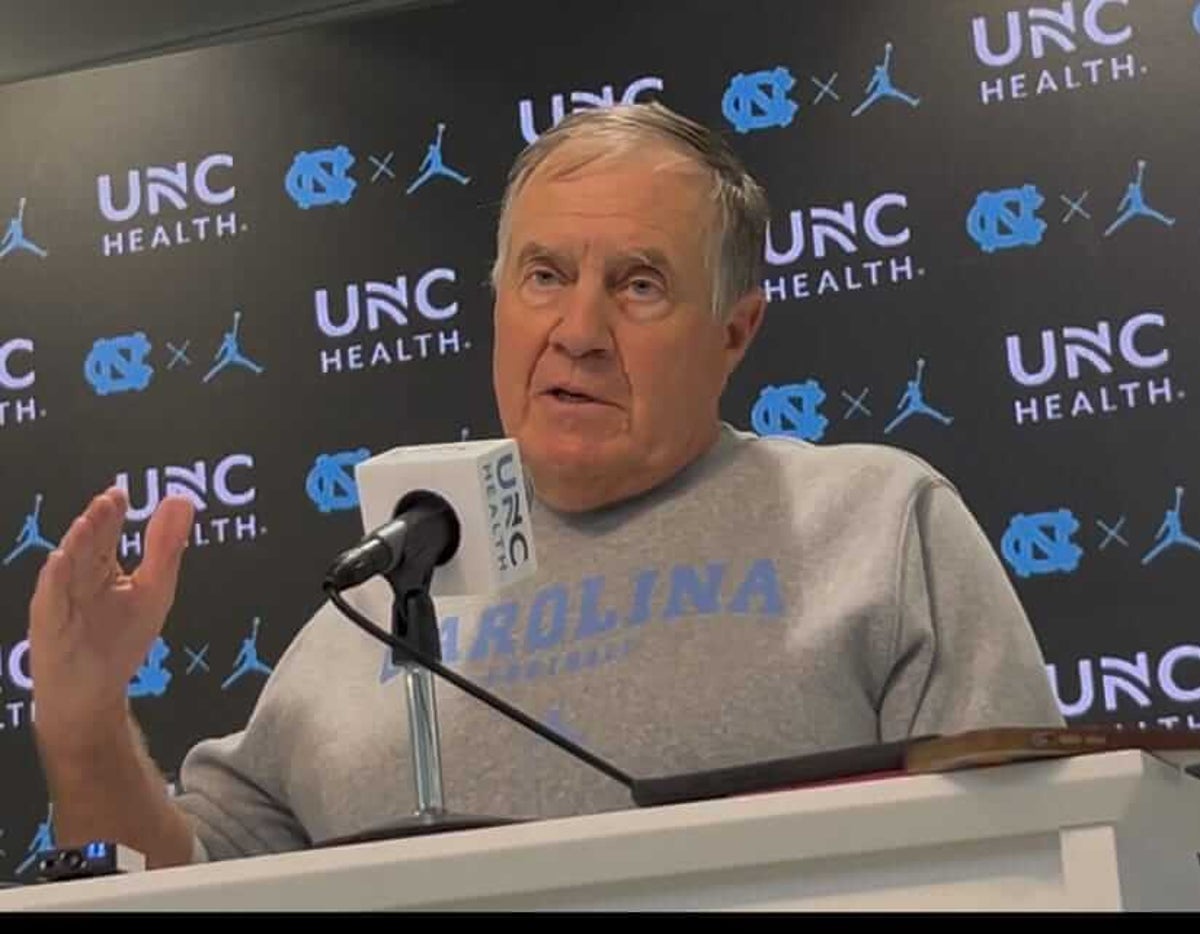

However, even as the college game morphs toward professionalization in the first season of the revenue-sharing era, the two levels still have notable differences that will loom for Reich and North Carolina’s Bill Belichick — two former NFL head coaches who had never been on a college staff before agreeing to lead one this offseason.

“College football is a unique and different challenge, from the schematics to the tempo to the recruiting,” said Wake Forest head coach Jake Dickert, who will face Belichick in November. “There’s a whole different world.”

Coaches with experience at both levels say the different worlds play out for college rookies in three main ways: less time with players, greater developmental opportunities and distinct roster management strategies. What the divergence looks like publicly will start to become clear Saturday when Reich’s Cardinal open at Hawaii and on Labor Day when Belichick — the six-time Super Bowl-winning head coach — debuts with the Tar Heels against TCU.

Less time with players

For Florida special teams coordinator Joe Houston, the most significant change from one level to the next is time. NCAA rules and academic schedules limit how long coaches can spend with players during game weeks.

“You get to meet with the NFL players for eight hours of the day, and then here there’s just such a small window of time you get to meet with them because they’re in class all morning,” said Houston, who joined the Gators last year after four seasons as a special teams assistant for Belichick’s Patriots.

The calendar presents a practical challenge: How do you teach younger, less experienced players with less instructional time?

Reich said the plays can’t be simplified much; an inside zone run is about the same regardless of level. Fundamentals are, too. However, Reich noted that some details can be adjusted. Instead of entering a game with a menu of 50 plays, it might be closer to 20. About 60 percent of the offense will be similar to what Reich used in the NFL, though perhaps with fewer shifts or motions that could complicate things.

“You’ve got to trust that (players are) going to do some work on their own, and you just can’t put too much in,” said Reich, who spent six years as an NFL head coach and twice led the Colts to the playoffs.

At North Carolina, Belichick’s goal is to run a system that mirrors the pros in everything from training to nutrition to terminology without overloading players.

Defensive back Will Hardy said the schemes haven’t been much more complicated than the defenses he learned under the Tar Heels’ past two coordinators. The changes under Belichick center on how much freedom Hardy and his teammates now have on the field.

“There’s maybe more on our plate mentally right before a snap,” Hardy said. “Things may not be fixed in stone. We see a different alignment, we may adjust to it, and we sort of have the freedom to do that ourselves.”

Frank Reich went 41-43-1 as coach of the Colts and Patriots. (Jim Dedmon / Imagn Images)More developmental opportunities

Although time with college players is a limiting factor during the season, Boston College head coach Bill O’Brien said that’s not the case during the offseason. While NFL players are out of the building from the end of their season until organized activities resume in the spring, college players go through winter conditioning, spring practice and summer workouts on campus. Those extra reps add up, which leads to a somewhat surprising conclusion.

“It’s harder to develop pro football players,” said O’Brien, who was head coach of the Houston Texans from 2014 to 2020.

Belichick noticed similar things during his first offseason with the Tar Heels. Padded spring practices, which aren’t allowed on the NFL calendar, led to what he called “tremendous” improvement in tackling, hand placement and other fundamentals.

If having younger, less skilled players limits any of the plays or concepts he can use, it’s an advantage on the practice field. Less experienced players have fewer bad habits to break and can be more receptive to change because their routines aren’t as entrenched.

“As a coach, it’s fun,” Belichick said. “It’s fun to see players get better, and then that gives them more momentum to keep working.”

Distinct roster management

O’Brien remembers studying short yardage cut-ups in Belichick’s office one weekday when an NFL general manager called. Belichick paused the chalk talk long enough to discuss the minutiae of a player contract situation, then hung up and immediately returned to O’Brien.

Now, on fourth-and-1 …

“I’m like, ‘How?’ ” said O’Brien, a Belichick assistant from 2007-11 and again in 2023. “That is incredible. No one will ever be able to do that, to go from a contract situation off the top of his head back to the short-yardage discussion.”

Belichick could. With schools now legally paying players, the ability to toggle between X’s and O’s and contract figures has never been more important in the college game. O’Brien said his pro experiences, including about 10 months as the Texans general manager, have made him comfortable having difficult financial conversations with players.

However, that experience only goes so far because of a fundamental difference between the levels.

“They draft. We recruit,” said Cal head coach Justin Wilcox, whose general manager (Ron Rivera) was an NFL head coach for Carolina and Washington. “Those contracts they sign are binding for multiple years. These are not. These are big, big differences we’re talking about.”

Wilcox said the differences affect salary strategies. NFL left tackles are usually among the highest-paid players on their team. However, what if a college team can’t successfully recruit an elite left tackle? Should it overpay for a second-tier talent, or save the money and spend it on another player or position group?

“You have to be ready to pivot,” Wilcox said.

At last month’s ACC media days, Belichick said his most significant adjustment was the sheer volume of players. With 53 players, NFL rosters are about half the size of college rosters (a limit of 105 plus any walk-ons who were exempted from this year’s rule change).

A couple of hundred players are realistic free-agent options in the NFL. In colleges, the transfer portal has thousands of players, many of whom played at lower levels and require more projections in scouting reports.

Then there are college-only tasks, like hosting prospects for seven-on-seven camps or recruiting multiple classes at the same time.

“If you want them, you’ve got to start getting in on them early,” Belichick said.

Will it work?

As Reich prepared to enter his first preseason camp at Stanford last month, he said he had no preconceptions about any of the teams on his schedule because everything was so new. The same, to some degree, holds for his Cardinal and Belichick’s Tar Heels because history doesn’t offer many clues.

Both levels have changed drastically since three-time Super Bowl champion Bill Walsh went 17-17 in his second stint as Stanford’s head coach (1992-94) after initially coaching the Cardinal in 1977-78. There are few recent precedents for former pro coaches with little to no college experience taking over major programs.

Lovie Smith was two decades removed from his time as a college position coach when he took over Illinois in 2016. After going 92-100 (.479) as the head coach of the Chicago Bears and Tampa Bay Buccaneers, he went 17-39 (.304) with the Illini.

Though Herm Edwards’ career started as a San Jose State assistant, he spent most of the next 29 years in/around the NFL as a scout, assistant, head coach (New York Jets and Kansas City Chiefs) and broadcaster. He went 26-20 at Arizona State and was fired in 2022.

Jim Mora had only graduate assistant experience at Washington when he got the UCLA job with a 31-33 NFL record (Atlanta Falcons and Seattle Seahawks). His 46-30 Bruins tenure ended with back-to-back losing seasons, but he has returned UConn to respectability.

In basketball, Mike Woodson had more than two decades of NBA coaching experience but no collegiate coaching experience when he got to Indiana. He left his alma mater in March after four underwhelming seasons.

Reich’s tenure will be short, regardless of what happens. He has said this is only a nine-month appointment to help Stanford general manager Andrew Luck through the season after the Cardinal fired Troy Taylor in March. Belichick and his five-year contract are different because he must navigate the ebb and flow of game preparation, player development and roster management.

For all the differences between the levels, Belichick has not sounded worried. The details have changed with his new job, but most of the keys to success have not.

“Fundamentals are the same,” Belichick said. “You earn your teammates’ respect from your daily actions. If you’re there all the time, and they depend on you and you’re accountable and you’re a good teammate, then you earn that.”

(Top photo: Rodd Baxley / The Fayetteville Observer / Imagn Images)