‘Turn to Stone’ shares one woman’s candid and hilarious confessions on dirtbagging, love, and the climbing lifestyle.

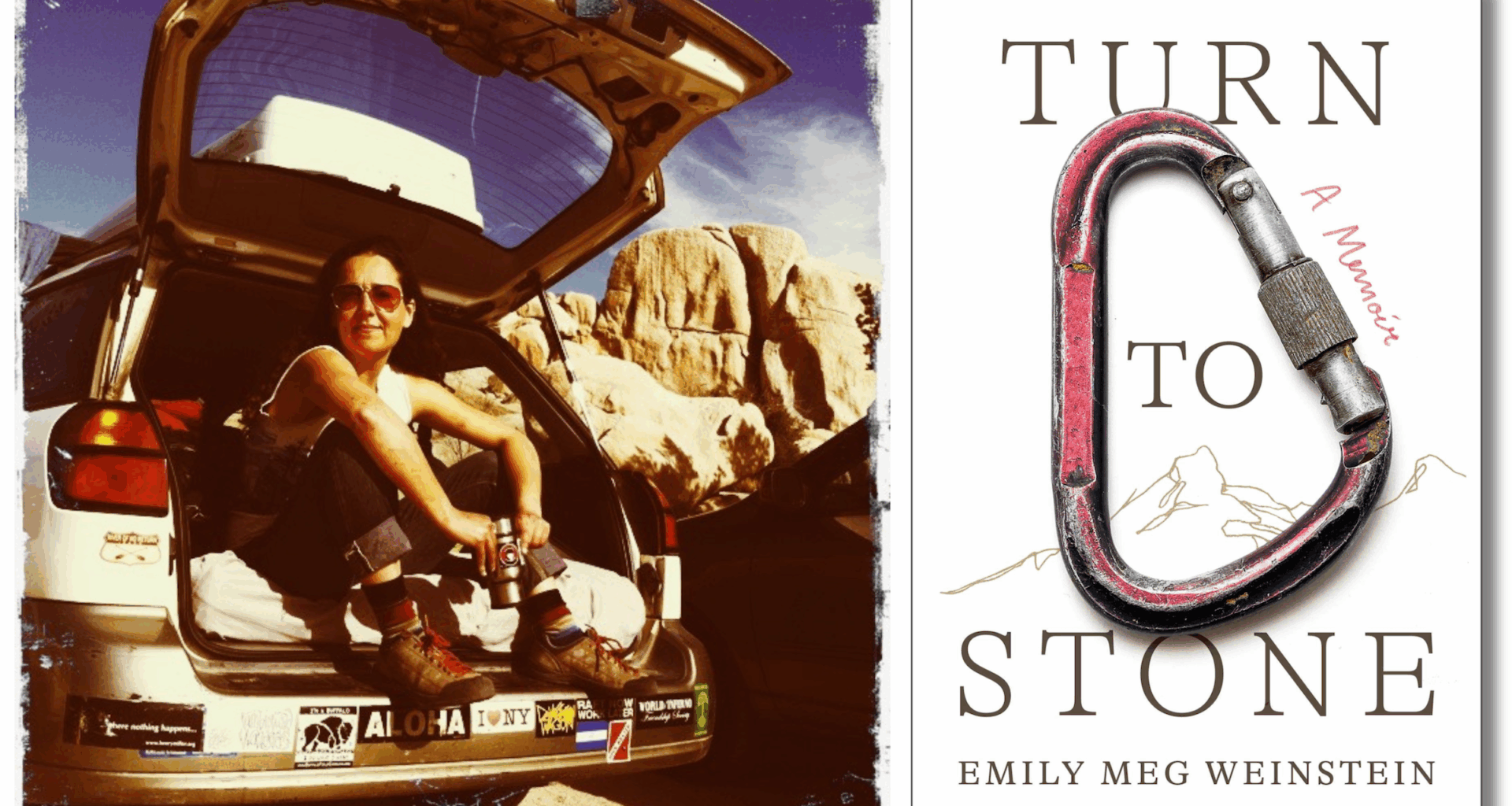

(Photo: Emily Meg Weinstein / Simon & Schuster)

Published September 1, 2025 04:03AM

The new memoir Turn to Stone is not your typical climbing read. For one, the author is not a pro climber reflecting back on their career. (She is admittedly average.) Nor does the narrative center upon an epic mission ending in historic success—or tragedy. (The book spans a seven-year period during which nothing particularly noteworthy is climbed.) And there is no point per se—no soapbox assumed or major issue tackled. So what is Turn to Stone?

“The book is a love letter to climbing and the climbing community,” says author Emily Meg Weinstein.

The reading experience for me felt more like the diary of an unlikely dirtbag. Weinstein looks back on her best years with humor, nostalgia, and the search for meaning. Before becoming a climber, the author was embedded in the punk rock scene of New York—and decidedly unathletic. In search of new purpose after escaping a toxic relationship, Weinstein stumbles upon Yosemite and falls in love with the sport. She moves into her Subaru (dubbed “Suby Ruby”) and tucks under the wing of a rotating cast of charismatic mentors. And, yes, she also dates a lot of climbers—and has a lot of sex.

(Photo: Courtesy Emily Meg Weinstein)

(Photo: Courtesy Emily Meg Weinstein)

What’s so enjoyable about this read is how relatable it feels to the ordinary climbers of the world (aka, most of us). Weinstein may not have put up first ascents, sent 5.15, or done anything to revolutionize the sport. Yet she fundamentally understands climbing and what it means to so many of us. She gets how it pulls you in and changes your life. To that end, she shares starkly honest vignettes about illegal camping, fear on the sharp end, the finer points of living in a vehicle, and the joys of personal progress. And with total candor, she recounts what it’s like to fall in (and out of) love with a climbing partner.

Even though I’ve never been to some of the main locales of the book or lived out of my car, Weinstein’s account felt familiar. The who, where, and what of climbing differ among all of us, but the how and why often unite us.

Like the best historians of cultural eras, Weinstein successfully captures the all-consuming magic of the climbing lifestyle in modern times. In that way, she has written a love letter to climbers. It’s a missive to the masses who haven’t done anything extraordinary on rock, but keep on climbing for the love of it.

Turn to Stone is available wherever books are sold on September 2. Below are some of my favorite (and among the funniest) quotes and passages from the book—keep scrolling for my interview with Weinstein.

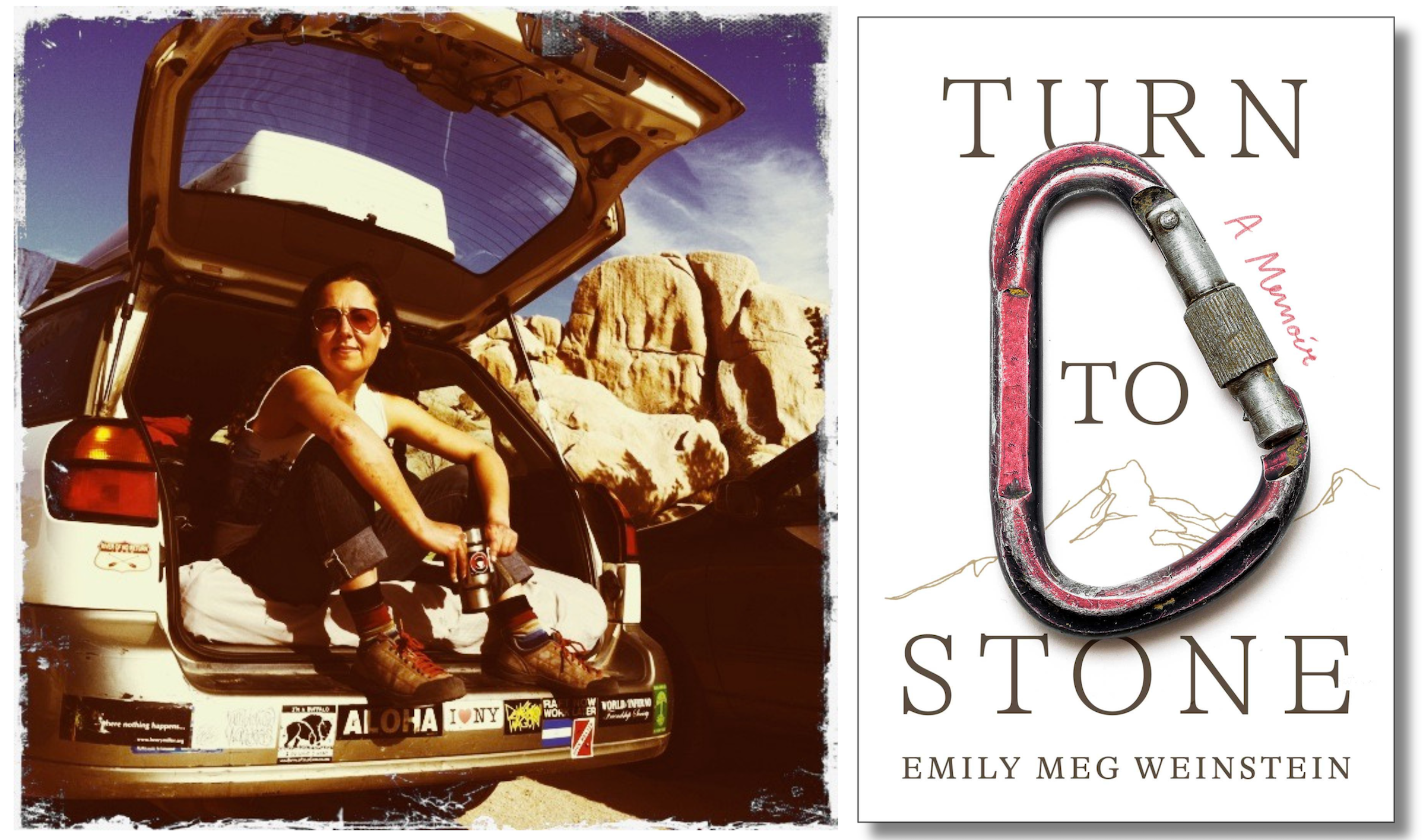

Climbing ‘Ranger Crack’ (5.8) in Yosemite

Climbing ‘Ranger Crack’ (5.8) in Yosemite

My Favorite Quotes From Turn to Stone

“We sat in the meadow, looking up at the big stone wall.

‘That’s El Capitan,’ he said. ‘I’m going to climb it one day.’

‘I’m going to write a book one day,’ I told him.

‘I’m sure you are,’ he smiled, ‘That will be your El Cap.’”

“For most of my life, I’d thought Joshua Tree was just the title of a U2 album. But it turned out it was also a place, in the desert east of Los Angeles.”

“The crack did not eat me. I did not let it. I did not let the chick with the perfect nachos and the perfect minivan and the perfect 5.12 boyfriend see me fail, or give up.”

“Underneath the body-wide bruise a new and deeper layer was forming, maybe somewhere in the marrow, a living part of me of which I’d never before been aware. I thought of superheroes busting out of their cutoffs, writhing in transformation from spider bites, caterpillars liquefying in their chrysalises before they sprouted wings. My hands looked like someone else’s hands. I was becoming something else, something new.”

“Climbing was the first thing that didn’t come easily to me that I did anyway. It was the first thing that actually quieted the demon of my own desire to destroy, or self-destruct. And being bad—or not that great—at rock climbing was exponentially more fun than being good at school. Nerds cared too much about school, but climbers didn’t even care about death.”

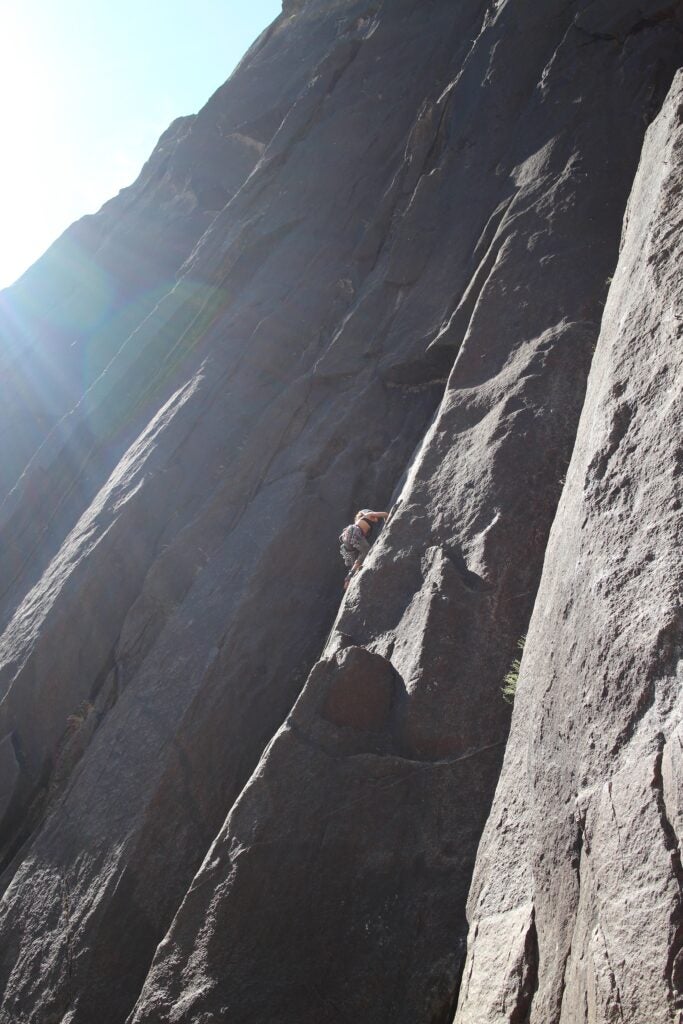

Weinstein on the Mari Gingery Route ‘On the Lamb’ (5.9) (Photo: Courtesy Emily Meg Weinstein)

Weinstein on the Mari Gingery Route ‘On the Lamb’ (5.9) (Photo: Courtesy Emily Meg Weinstein)

“Growing up, I was scared of rooms without windows and didn’t know why. I was scared of the dark, scared of the night … But up in the Meadows, up on the wall, with those Jedi Stonemasters, there was so much room, and light, and air … I felt safe, utterly safe, even hanging from one nut—one good nut—hundreds and hundreds of feet above the ground, safer in the vertical than I felt on the ground. In a way, I was re-parented, in the vertical, by two Stonemasters from Southern California who never had kids of their own but have adopted many misfits like myself, loved them well, taught them all they knew—and set them free.”

“In the time it took me to assess the size of the spot in the rock where I’d stopped to rest and select a piece from my harness, Honnold, unencumbered and shirtless, climbed up from the ground until he was just below me.

‘Hey,’ said Alex Honnold, nodding politely as he soloed past.

‘Hey,’ I replied, trying to look as casual as he did.”

“‘I have a theory about 5.12.’

‘What’s that?’

‘5.12 is the douchiest level. It’s the level of climbing that makes people the most douchey.’

‘How did you discover this? Did you become a douche?’

‘Not yet,’ he said. ‘But the more I climb 5.12, with the other 5.12 climbers, the more I confirm this theory.’”

“And with that promise, I laid down my arms, and said a silent prayer of thanks to all the crushers who hung the ropes on the hard pitches. Even if they couldn’t marry me and give me babies, even if they didn’t want to be in a committed relationship, even if they were more afraid of intimacy than free soloing, even if they couldn’t find it in their hearts to accompany me into the dark night of the soul, or accompany me into more than a few of them, they had helped make me fierce enough to face it on my own.”

The quotes above are excerpted from TURN TO STONE. Copyright © 2025, Emily Meg Weinstein. Reproduced by permission of Simon Element, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Q&A with Emily Meg Weinstein, author of Turn to Stone

Climbing: You pitched this book as “Sex and the City meets rock climbing.” What parallels do you see between the show (or even its successor And Just Like That) and its themes within your own past life as a dirtbag?

Emily Meg Weinstein: As a curly haired, chronically single, New York woman writer who came of age right as the original series dropped, the influence was inevitable. Turn to Stone is a confession about what it’s like to be an adventurous and artistic woman in her 30s, who likes sex and wants love—which is, sadly, a radical enough story in these inhuman and patriarchal times.

But Sex and the City isn’t the only influence or text from which I drew inspiration. The late feminist and Playboy columnist Cynthia Heimel is one of my idols for writing about sex, drugs, and rock and roll in 1980s New York, specifically in a forum where she could reach male readers as well as female ones.

There are absolutely no parallels between the Sex and the City reboot And Just Like That and my own dirtbag experience. Though I did use what I can’t even pretend was a hate-watch of the mercifully final season as a pleasant diversion during the final phase of launching this book.

Climbing: How else does this book depart from the more traditional climbing or adventure read?

Weinstein: I envisioned the book as a 21st century feminist version of woefully dead, white male, road-and-wilderness classics like On the Road, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and Ed Abbey’s Desert Solitaire—but with more sex and feelings, which are seen as traditionally female.

Climbing: How would you describe the chapter of your life captured in this book? And to what extent, did you identify as a dirtbag during that period?

Weinstein: Turn to Stone is about my first seven or so years as a climber. I wasn’t a full-time dirtbag. I always had a home, though for a while it was an illegal occupancy of an art studio in a former military barracks, or a tiny cabin too small for a couch. But I climbed in Yosemite or Tahoe a weekend or two each month, went to Joshua Tree multiple times each year, and roamed the West and the country in all seasons. I climbed for weeks at a time in the summers, when I was off from my day job tutoring teenagers.

The time we got an Airbnb in Vegas for Thanksgiving in Red Rock in 2016 or 2017 was the beginning of the end for me sleeping in my vehicle for long periods of time. I have become embarrassingly attached to indoor plumbing, especially for writing purposes. My Long Island roots are showing.

(Photo: Courtesy Emily Meg Weinstein)

(Photo: Courtesy Emily Meg Weinstein)

Climbing: Climbing has changed a lot since the period documented in your book. What’s the most surprising way in which climbing has evolved?

Weinstein: Since I started climbing in 2011, climbing has changed in one major way for the better: It’s become more diverse and accessible to folks of more racial, sexual, and gender identities; body sizes, abilities, and disabilities; and even levels of wealth. With the mainstreaming of high-profile climbing stories like Honnold’s Free Solo or the more recent Girl Climber, climbing has become more familiar to people who don’t climb. I’m stoked on that because I think it made space for me to write this memoir, which I see as the first truly mainstream, literary climbing memoir.

The way that climbing has changed for the worse parallels the way our country and the world have changed from 2011 to 2025. More wilderness areas are under threat of mining, oil drilling, and other forms of destruction under the Trump administrations. Because of the rising tide of American fascism, many of the rural areas where climbing often takes place have become, I think, even more frightening for anyone who isn’t white and/or gender-conforming. A lot of the parking lots I once slept in and wilderness “bivies” where I spent the most joyous years of my life are now off-limits to climbers, campers, and travelers.

But as my favorite astrologer Chani Nicholas would say, rocks don’t change very much in a decade or two. They don’t change much in a century or even a millennium. Sometimes they change really fast—parts of routes I’ve climbed have since fallen off—but they mostly stay the same as we humans age and soften and slowly turn to dust.

Climbing: Yosemite plays a major role in your memoir. When’s the last time you were back in Yosemite?

Weinstein: I snuck off to Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite for a quick “book babymoon” pre-launch. Though I barely touched rock and was embarrassingly weak when I did, the granite was the same as ever. The river was flowing. The peaks I’d once touched still loomed above. Talking shit with my climbing buddies was as pleasant as ever.

There is another generation of dirtbags coming up, sleeping in Honda Civics and sending for the pure joy of it. What we love most about it will never die. It will just get harder, as the world burns hotter, which means that the next generation will be even more rad.

On ‘Angel’s Crest’ (5.10b) in Squamish (Photo: Matt Berke)

On ‘Angel’s Crest’ (5.10b) in Squamish (Photo: Matt Berke)

Climbing: How has your own relationship with climbing evolved since the days you write about in Turn to Stone? Are you still all about the moderate trad routes?

Weinstein: I will always be all about the moderate trad routes. I’m too weak of flesh and ankle to boulder, and I really like getting high in every possible way. There is something about a continuous, protectable 5.7 hand crack that fixes something that is broken in my brain and soul. And I just really love, and prefer, the granite where I fell in love with climbing.

I felt really badly about how little I climbed while I wrote my book until I read that Tommy Caldwell didn’t climb for a year when he was writing his. The pandemic, and later the book, radically changed the texture of my climbing life.

Like most climbers in their 40s and beyond, I’m evolving into a trad dad weekend warrior. Climbing is more a part of my life than the whole. I miss the times when it was everything. I knew what to do at every moment of the day.

Climbing: As you were writing, did you imagine speaking to non-climbers to convey the magic of the climbing lifestyle? Or were you picturing climbers as readers, prompting them to look back on their own journey?

Weinstein: My ideal reader is pretty much anyone and everyone! I really imagined, sold, and wrote this memoir very deliberately for non-climbers and climbers alike. I think climbers will read this and resonate deeply with it. I’m also hearing from early readers who aren’t climbers that it’s very relatable for them, because I “write about climbing in such an appealing and super-legible way, from a non-climbing perspective,” according to a poet friend.

Also, during my interview on The Runout, Chris Kalous told me I had “captured the magic of climbing,” which was my ultimate goal. So I think that this book is also for anyone who likes and believes in magic.

But my ideal reader is anyone, including Timothée Chalamet, who could be very well-cast as an amalgamated noncommittal climber boyfriend character in the movie version of this book, and Natalie Portman, who I think could both star and produce.

Climbing: Your book is packed with emotion, sex, and wit, which is not necessarily the norm for climbing literature. Do you think climbing stories ought to have more fun?

Weinstein: We need to break down more barriers of genre so that emotion, sex, and wit—as well as pain, joy, death, fear, radical honesty, politics, philosophy, ideas, and maybe even baseball—can all be part of serious mountain literature, and that people can tell their stories in all their complexity and dimensionality.

More lately, pro climber Steph Davis wrote gorgeously about love and loss in her memoir, Learning to Fly. Beth Rodden’s recent memoir, A Light Through the Cracks, also deals with more emotional material, alongside the quite hardcore climbing narrative.

But you’re right—a climbing podcast interviewer said that it almost felt “taboo” that the book is at least equally about the more universal experience of sex as it is about going up and down rocks. Part of that is that I simply don’t climb very hard. Another part of that is that I’d rather describe my own desire, rage, horniness, pain, longing, and constantly running stoner brain than another tree, cloud, or even hunk of granite. Also, whether you’re FA-ing 5.14 or plod-romping up a moderate trad route, the shit that happens is surprisingly similar.

We should all worry less about genre and write as freely as we climb.