Tri didn’t copy aero – it taught it. Here we look at the historic images, oddities, and athletes who hid heads, moved bottles, and nudged rules to reshape the way we look on the bike leg.

(Photo: Triathlete)

Published September 3, 2025 09:51AM

The evolution of the aero position on the bike in the sport of triathlon

Triathlon has always been a little allergic to staying inside the lines. The first years were road bikes, toe‑clips, and guts – no aerobars, no deep dish wheels. Then came a tsunami of innovation on a July afternoon in France in 1989: a pair of narrow extensions and a tucked head that changed how everyone thought about going fast.

In the decades between, our positions have swung from tall and tidy to pancake‑flat and back toward high hands and hidden heads. What follows is a photo‑led tour of how triathletes invented aero, accidentally detoured into fashion, and – finally – rediscovered what the wind was trying to tell us all along.

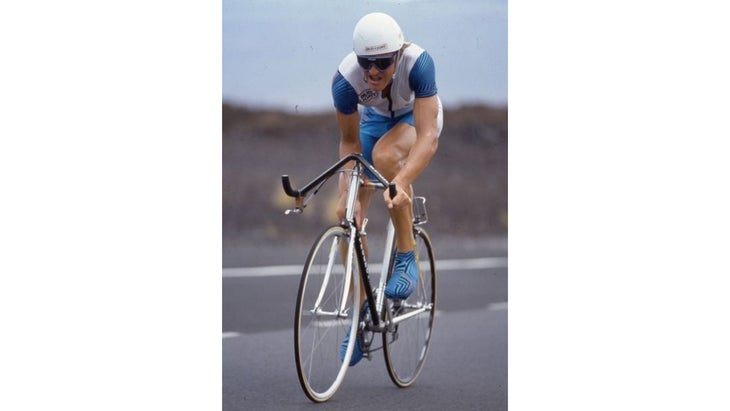

Before aero: road bars and stubborn headwinds (early 80s)

Road bars, tall posture – the sport before clip-ons. (Photo: Mike Plant)

Road bars, tall posture – the sport before clip-ons. (Photo: Mike Plant)

In the beginning, there were road bikes – steel or early aluminum frames with round tubes, down‑tube shifters, and drop bars. Kona, Nice, and the other early classics were tests of position you could hold for hours, not positions purpose‑built for the wind.

Athletes choked up on the tops for long grinders or dove into the drops for descents; the body was tall, the elbows wide, and the head fully exposed to clean air. “Integration” meant electrical tape, foam pads, and extra bottle cages. It wasn’t slow – just honest. If you wanted to go faster, you pedaled harder.

The spark: LeMond’s Scott DH bar and the tri spillover (1989)

In 1989 American Greg Lemond debuted aerobars at a time-trial stage in the Tour De France. (Photo: AFP via Getty Images)

In 1989 American Greg Lemond debuted aerobars at a time-trial stage in the Tour De France. (Photo: AFP via Getty Images)

The innovation that changed everything didn’t come from a wind tunnel press release – it came from a live TV time trial at the Tour de France. Greg LeMond’s narrow clip‑on aerobars (licensed by Scott from ski coach Boone Lennon’s bar patent) put his forearms slightly high of parallel, pulled his shoulders in, and gave his head somewhere to hide.

Lemond’s win was tiny in margin and massive in consequence. Overnight, clip‑on aerobars jumped from garage experiments to must‑have kit. Triathletes – already the most shameless tinkerers in cycling – bolted them to anything with two wheels and started testing stack, reach, and elbow width by feel, stop‑watch, and race photos. The geometry and hardware were crude, but the idea was crystal clear: shrink frontal area, keep the head out of the wind, and hold it for hours.

The pioneer: Tinley’s high‑hands, low‑head experiments (mid‑80s to early 90s)

Tinley lifts the hands and tucks the head – decades before it was cool. (Photo: Lois Schwartz)

Tinley lifts the hands and tucks the head – decades before it was cool. (Photo: Lois Schwartz)

Before wind‑tunnel fashion hardened into dogma, Scott Tinley (aka “Hi-Tech Tinley”) was already playing with the shapes we now call modern. Study the photos: hands subtly higher than elbows, elbows closer together, chin tucked into the pocket between the forearms. The aerodynamics are simple and durable – raise the hands and the helmet naturally drops; narrow the elbows and the shoulders disappear.

Tinley lifts the hands and tucks the head – decades before it was cool. (Photo: Lois Schwartz)

Tinley lifts the hands and tucks the head – decades before it was cool. (Photo: Lois Schwartz)

Tinley wasn’t alone, but he was early and visible, and he proved that comfort and control could coexist with a smaller silhouette. Here’s the twist: Much of the market copied the hardware (clip‑on aerobars) and missed the lesson (hide the head). What followed was a long, flat era that looked fast in pictures but often wasn’t in the data.

Side Quest — The hydration arms race (then and now)

1990s: Front hydration shows up between the arms because that’s where your hands already split the air. Refillable bottles with straws (think Profile Design Aerodrink) make sipping easy and fill the low‑pressure pocket in front of the chest. Elegant? Not really. Effective? Often, yes.

Simple BTA placement that can smooth flow around the hands. (Photo: Kurt Hoy)

Simple BTA placement that can smooth flow around the hands. (Photo: Kurt Hoy)

Late 2000s: Round bottles migrate horizontally between the forearms. Done right, a single BTA can be neutral or even slightly helpful by smoothing flow around the fists and giving the head a “wall” to hide behind. Done wrong (too wide, too low), it’s just a sail.

Before his double BTA made a debut, Lieto was rocking this power position (Photo: Paul Phillips)

Before his double BTA made a debut, Lieto was rocking this power position (Photo: Paul Phillips)

Double‑stacks: The Chris Lieto era popularized two bottles between the arms. Sometimes brilliant, sometimes brutal. The result depends on rider width, yaw, and whether the helmet stays tucked behind the tops of the bottles.

Integration pushes right up to the no-fairings line.

Integration pushes right up to the no-fairings line.

Integration & bladders: Frames and nose‑cones flirt with internal bladders and sculpted fronts (see: CAT Cheetah, Badmann). They preview today’s clean cockpits but also push against the spirit of “no fairings.”

Today: BTA is a system, not a bottle. Athletes pair modest tilt, narrow elbows, and a single front reservoir that’s placed to help shield the face – and act as a legal fairing. Most rule sets are explicit that hydration must be functional (drinkable) rather than a shaped cover; integration is welcome. Finally, over 30 years: The fastest setups make hydration serve the position, not the other way around.

The flat‑arm era: fast on camera, not always in Kona (mid‑90s to ~2010)

Hands below elbows – fast on camera, not always in air.

Hands below elbows – fast on camera, not always in air.

As innovative as Scott Tinley was in the 80s, he turned a bit more fashion avant-garde in the 90s and started a new trend of flat arms. This was a purely aesthetic option that was thought of as fast but really failed most wind tunnel tests. TV loved a low, flat silhouette. Early bike fitters prized hip‑angle preservation over head shelter, and most aerobars in this era simply couldn’t tilt much (or at all). The look spread: hands eventually went below elbows, forearms were angled down (thinking it was faster to get the hands lower), chin out in clean air. Icons of the time – world‑class riders like Michellie Jones, Julie Dibens, and Chris Lieto – went blisteringly fast anyway, because engines matter.

We later realized that riding with hands below elbows created a ton of extra drag. Meanwhile, a few contrarians (Björn Andersson and pockets of age‑group tinkerers) were already sneaking in elbow squeeze and modest tilt, planting seeds for a pivot that would take another decade to bloom.

Hardware catches up: 3D printing changes everything

Advances in 3D printing have lead to an evolution in custom aerobars, like Lucy Charles-Barclay’s 2023 Ironman World Championship setup. (Photo: Brad Kaminski)

Advances in 3D printing have lead to an evolution in custom aerobars, like Lucy Charles-Barclay’s 2023 Ironman World Championship setup. (Photo: Brad Kaminski)

By the mid‑2010s, consumer/hobby 3D printers and cheap scanning blew the doors off cockpit iteration. Fitters and small shops could print arm cups, tilt wedges, bridge pieces, and even one‑piece mono‑posts overnight, ride‑test them the next day, then send the winning shapes to be laid up in carbon.

A cottage industry sprang up – boutiques like Uniqo building truly custom cockpits that start life as printed prototypes and end as molded composites – so the hardware finally kept pace with what the wind (and fitters) were asking for. This is a big reason the high‑hands/low‑head “mantis” made a rapid comeback: The parts now existed to make it comfortable, stiff, and legal.

Course correction: the comeback of high hands (2010s to today)

Elbows in, slight tilt, head hidden – foreshadowing modern shapes.

Elbows in, slight tilt, head hidden – foreshadowing modern shapes.

Two things changed: testing and tools. Field testing aerodynamics with affordable power meters, more accessible tunnels/CFD, and thousands of race photos on social media made it obvious that forearms can act like fairings for the head. At the same time, tilt wedges, deep arm cups, mono‑posts, and then hobby‑printer prototypes let athletes make that shape comfortable. The modern “mantis” isn’t a gimmick; it’s a recipe: narrow elbows, modest extension tilt, shoulders shrugged, head tucked into the pocket.

High-hands silhouette returns to the mainstream.

High-hands silhouette returns to the mainstream.

Look at Gustav Iden and Joe Skipper in recent seasons – hands up, face hidden, bottles placed to help the posture rather than fight it. A decade earlier, the author was already there – racing a pronounced mantis with stacked front hydration, then winning Ironman Lake Placid 2011 on a 1996 Zipp 2001 beam bike using DIY arm supports (yes, “nut cups” and soccer shinguards) after debuting the look on his 2009 Triathlete magazine cover. He didn’t invent the idea, but he dragged it back into the mainstream. The result is not just lower coefficient of aerodynamic drag (CdA); it’s a position you can actually hold for 180km while eating, drinking, and steering.

Forearms as fairings, head hidden between the fists. (Photo: Brad Kaminski)

Forearms as fairings, head hidden between the fists. (Photo: Brad Kaminski)

Outliers & oddities that moved the goalposts

Monobar minimalism to narrow the rider – way ahead of its time. (Photo: Lois Schwartz)

Monobar minimalism to narrow the rider – way ahead of its time. (Photo: Lois Schwartz)

Erin Baker’s monobar: A minimalist path to width reduction long before 3D printing was available

Gudmund Snilstveit’s “Unicorn”: One‑sided extension that proved tri’s appetite for fringe solutions (and rider confidence)

Joe Skipper bottle fairings: Turning aero-shaped water bottles into pure wind fairings was next level with Skipper’s bottles outside his elbows and under his chest

CAT Cheetah & Badmann’s bladders: Early integration that previewed today’s legal‑but‑clean hydration. These weren’t mass‑market successes, but each asked a useful question, and the mainstream answered years later.

What’s next (and what rules will allow)

Expect more 3D‑printed, rider‑specific cockpits that combine tilt, cup depth, and grip shape into one rigid unit; smarter BTA reservoirs that are drinkable yet easy to refill on the go; and clearer rule language that distinguishes function from fairing without strangling innovation.

Don’t be surprised if transparency tests for front bottles (can you see fluid? can you drink from it while moving?) become commonplace at big events. And for age‑groupers, the future is better testing: on‑bike sensors and easy field protocols to validate changes outside a tunnel.

Evolution required

Triathlon didn’t stumble into aero – it built it piece by piece. We borrowed a spark from LeMond, yes, but the sport’s constant garage‑level iteration created today’s high‑hands, low‑head look. The lineage from “Hi-Tech” Tinley’s experiments to Iden’s cockpit is simple: hide the head, narrow the body, and make hydration serve the position. The rest is just hardware – and now we finally have the right tools.