Updated November 21, 2025 11:04AM

Nicknames just aren’t what they used to be.

For a sport steeped in mythology and legend, modern cycling sure has lost its flair for the poetic.

Today’s highly tuned and optimized peloton is an antiseptic shadow of the sport’s glory days, when riders and their colorful monikers matched the drama and emotion on the road.

“Il Campionissimo,” “The Badger,” “El Diablo,” “The Lion of Flanders” — these were the catchphrases and aliases that spoke to the masses.

These wildly descriptive and catchy nicknames helped make cycling seem almost cinematic and lit up the newspapers, radio, and TV of the day.

These wonderful and sometimes wacky petit nom were bestowed by fans, by journalists, and by rivals, who wanted a shorthand version to describe the larger-than-life exploits that were otherwise beyond words.

What better way to sum up Eddy Merckx and his insatiable appetite for victory?

The Cannibal, of course.

But somewhere between the dawn of power meters and the rise of social media, the nickname tradition has seemingly died on the vine.

Today’s stars have been reduced mostly to non-offensive abbreviations and first-syllable mashups.

WOWt. MVDP. Pogi. PFP. Rogla. Vingo.

Come on, folks, we can do better than that.

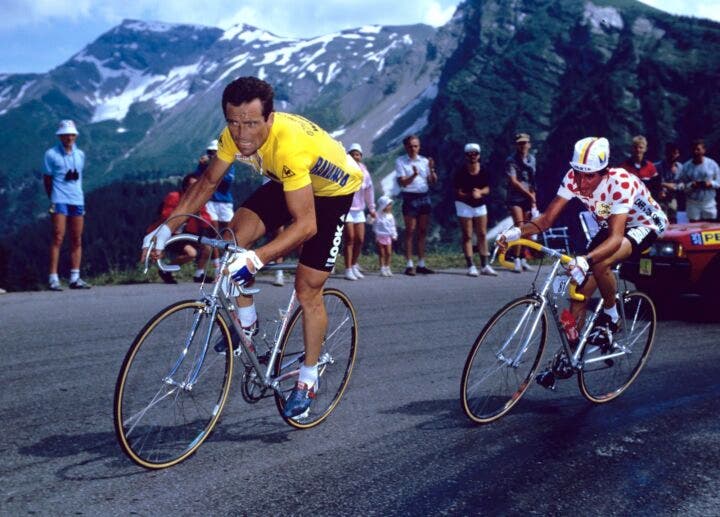

The Badger and the ‘escarabajos’

Hinault fends off Luis Herrera, one of Colombia’s ‘escarabajos’ from the 1980s. (Photo: Graham Watson/Getty Images)

Hinault fends off Luis Herrera, one of Colombia’s ‘escarabajos’ from the 1980s. (Photo: Graham Watson/Getty Images)

Cycling’s delivered some of the most memorable and descriptive nicknames in the history of sport.

Babe Ruth might have been the “King of Swat,” and Joe Namath might have been “Broadway Joe,” but that’s nothing compared to the “Tashkent Terror,” the fearless Uzbek sprinter Djamolidine Abdoujaparov who terrorized the sprints in the 1990s.

From its earliest days, cyclists and their larger-than-life exploits captured the imagination of fans and headline writers alike.

And using a two-wheeled version of a nom-de-guerre was a perfect way to describe the essence of the heroes on spokes.

Jacques Anquetil, the first rider to win five yellow jerseys, was Monsieur Chrono, Mr. Time Trial. Fausto Coppi became “Il Campionissimo,” the champion of champions.

Charly Gaul, from Luxembourg in the Low Countries, was “The Angel of the Mountains,” while suave Swiss star Hugo Koblet was the Pédalleur de Charme, “The Pedaler of Charm.”

Fabian Cancellara was Spartacus, and Caleb Ewan was the Pocket Rocket, monikers that summed up their characters and captured their racing genius in a few succinct words.

These nicknames have carried across the passage of time and helped fans identify with their steel-wheeled superheroes.

Fédérico Bahamontes, Spain’s first Tour winner, was the Eagle of Toledo for the way he soared across the Alps and Pyrénées.

An entire generation of Colombian climbers in the 1980s became the “escarabajos” — the beetles — for the way they clawed up the steepest climbs in the world.

The 1980s and 1990s were the glory days of some of the best nicknames.

Bandana-wearing Marco Pantani became the larger-than-life figure as Il Pirata, “The Pirate,” for his flamboyant and swashbuckling raids. Claudio Chiappucci was “Il Diablo,” and Tom Boonen was crowned “Tomeke” and “Tornado Tom” for the way he stormed across the pavé.

Bernard Hinault held a legendary surnom as Le Blaireau, The Badger, a title he loved for its — and his — obstinate character.

Vos the Boss and ‘La Pantanina’

Vos is arguably women’s racing’s greatest ever. (Photo: Luc Claessen/Getty Images)

Vos is arguably women’s racing’s greatest ever. (Photo: Luc Claessen/Getty Images)

The tradition isn’t as ingrained in women’s racing, but there have been some standouts.

Marianne Vos, arguably the greatest women’s cyclist ever, is simply the GOAT. Or Vos the Boss.

Fabiana Luperini, who ruled the roads of the 1990s, was dubbed “La Pantanina,” the Little Pantani, by the effervescent Italian media.

Dutch journalists called double Olympic champion Leontien van Moorsel “Tinus,” short for greatness.

Nicole Cooke was the “Welsh Wonder,” and Kristin Armstrong is “KiKi” and “K-Strong” for her unprecedented treble of Olympic golds in the time trial.

Teams also earn nicknames. Euskaltel-Euskadi was the “Orange Tide” for its trademark jersey and penchant for lighting up the Pyrénées when fans traveled from País Vasco to choke the roads.

Team Sky became “Fortress Froome,” and Quick-Step calls itself the “Wolfpack” for its all-for-one mentality.

Today’s “Killer Bees” pack a sting at Visma-Lease a Bike.

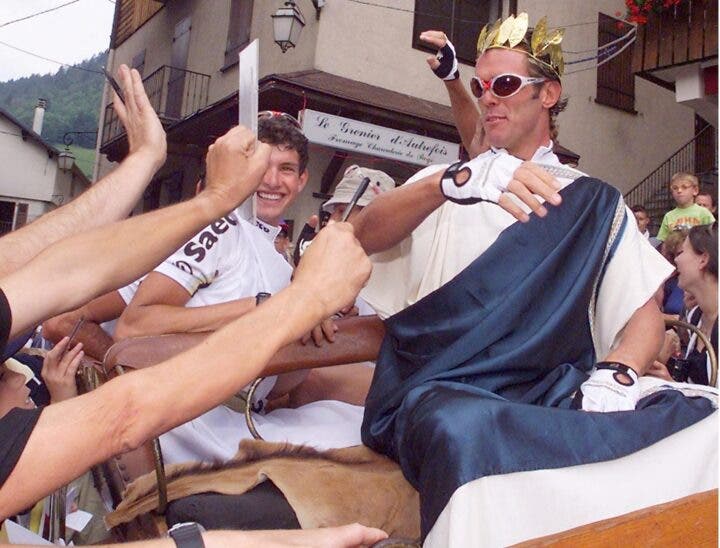

From the illicit to the Lion King

Cipollini, aka the Lion King, once showed up at the Tour de France dressed like Julius Caesar. (Photo: PASCAL PAVANI/AFP via Getty Images)

Cipollini, aka the Lion King, once showed up at the Tour de France dressed like Julius Caesar. (Photo: PASCAL PAVANI/AFP via Getty Images)

Not all nicknames are welcomed or deserved.

Michael Rasmussen became “The Chicken,” after a kid’s TV character, and he was never thrilled about that one. Cadel Evans was known affectionately as “Cuddles” for his gentlemanly demeanor in a brutal sport.

Louison Bobet, France’s first post-war cycling hero, perhaps didn’t pack the same gravitas as his palmarès with his moniker as the le boulanger de Saint-Méen, the baker from Saint-Méen.

Some got theirs out of doping investigations. The infamous Operación Puerto scandal was a treasure-trove of illicit nicknames, like “Birillo”, “Zapatero,” “Val-Piti,” or “Hijo de Rudicio” (we’ll let you link the names to the rider).

Two of cycling’s most notorious figures had dual nicknames to reflect their double-dealing ways. Riccardo Riccò was at once “The Cobra” and “The Pharmacist.” Bjarne Riis was known as “The Eagle of Herning” as well as “Mr. 60 Percent.”

Sport directors and managers also earned their own sobriquet for their sometimes-firm management styles.

Giancarlo Ferretti, the long-time DS of Fassa Bortolo, earned the well-known nickname of il Sargente di Ferro, or the “Iron Sergeant.”

Recently retired Patrick Lefevere was “The Godfather,” and Cyril Guimard was Le Patron, or simply the boss.

El Pistolero to Il Grillo

Contador was called ‘El Pistolero’ for his trademark finish line victory salute. (Photo: David Ramos – Velo/Getty Images)

Contador was called ‘El Pistolero’ for his trademark finish line victory salute. (Photo: David Ramos – Velo/Getty Images)

Nicknames played off a cyclist’s style and flair on or off the bike.

Alberto Contador was the El Pistolero, and Alejandro Valverde was christened Bala Verde, the Green Bullet. Laurent Fignon was Le Professeur, and Greg LeMond L’Americain.

Mark Cavendish was the Manx Missile, Jan Ullrich Der Kaiser, and stoutly built domestique Tim DeClercq became The Tractor, all five-star names.

There are plenty of riders whose names were inspired by animals.

Brawny André Greipel was The Gorilla, dashing Daniele Bennati The Panther, and speedy Óscar Freire was El Gato, the cat, all spot on when you saw them in person.

The Italians are particularly prolific with nicknames. Franco Pellizotti was the Dolphin of Bibbione (“Delfino di Bibbione”), Domenico Pozzovivo was known as The Flea, and Paolo Bettini was Il Grillo, or the cricket, for how he bounced from win to win.

Vincenzo Nibali, Italy’s last Tour de France winner, was The Shark of the Strait (“Squalo dello Stretto”), and today’s TT king Filippo Ganna is Top Ganna, from well, you can guess.

Even minor riders could pick up nicknames, like one Spanish rider who was called the “Jabalí del Bierzo,” the wild boar from Bierzo.

JaJa to Mini-Phinney

Mini-Phinney, right, poses with the Cannibal and the Manx Missile. (Photo: Bryn Lennon/Getty Images)

Mini-Phinney, right, poses with the Cannibal and the Manx Missile. (Photo: Bryn Lennon/Getty Images)

Nicknames also reflect a rider’s geographic or national background.

Lance Armstrong was “Big Tex” as well as “Mellow Johnny,” though there wasn’t much mellow about that fellow. Richie Porte was the “Tasmanian Devil,” and Rik Van Steenbergen was “The Emperor of Herentals.”

The French love their diminutives: Julian Alaphilippe is LouLou, Laurent Jalabert was JaJa, and Raymond Poulidor, the eternal second, was affectionately known as PouPou.

The Aussies have their own way of shortening theirs. Everyone from Down Under is Whitey, Stuey, Robbie, Mattie, or Platty. Michael Woods, though Canadian, is Woodsy, still part of the Commonwealth.

Italians bring a penchant for drama. Mario Cipollini — the master of hype who once showed up to a Tour de France stage start dressed up like Julius Caesar — was Il Re Leone, the Lion King.

Two-time Giro winner Damiano Cunego was the Little Prince of Verona (“Principino Veronese”), while Danilo Di Luca was The Killer, and Gino Bartali was known both as The Man of Iron (“L’uomo di ferro”) and Gino the Pious.

Sometimes names are generational.

Taylor Phinney was “Mini-Phinney,” after his father, racing legend Davis Phinney. Thibau Nys is “Baby Nys,” picking up his CX legendary dad, Sven.

France Olympic mountain bike champion Miguel Martinez was called “Little Mig,” inspired by his contrasting stature to Spain’s Miguel Indurain, known as “Big Mig.”

So what do we call his son, Lenny Martinez? Mini Lenny?

Why nicknames have faded

Del Toro is among a modern generation of riders with a solid nickname in ‘El Torito,’ the Little Bull. (Photo: Dario Belingheri/Getty Images)

Del Toro is among a modern generation of riders with a solid nickname in ‘El Torito,’ the Little Bull. (Photo: Dario Belingheri/Getty Images)

So why have nicknames largely fallen out of favor?

Part of it is how athletes can control the narrative of their careers much more than before. When journalists started calling Tadej Pogačar the “Slovenian Slayer,” he put the kabosh on that because he didn’t like the militaristic connotation.

In today’s world, nicknames can seem demeaning or even anachronistic to some.

Social media has changed the way stars connect with their fans.

Top riders like Wout van Aert and Demi Vollering reveal their everyday lives with their millions of fans via Instagram. They’ve bypassed the media entirely and speak straight to their audience. Fans can follow along as Van Aert plays hoops with Reggie Miller or go on an off-season hike with Vollering in the Alps.

Journalism has changed, too. The sports pages today are less about long-form reportage and character-driven storytelling than stats, data, hot takes, controversy, and clickbait.

And in today’s 15-second attention span, there’s hardly any wavelength left for playing with words or building up personalities.

If someone doesn’t like it, they just swipe left.

‘GC Kuss’ and ‘Landismo’

‘GC Kuss’ celebrates with ‘Vingo’ and ‘Rogla’. (Photo: Alexander Hassenstein/Getty Images)

‘GC Kuss’ celebrates with ‘Vingo’ and ‘Rogla’. (Photo: Alexander Hassenstein/Getty Images)

There are some contemporary exceptions.

Mikel Landa brings his own mysticism with Landismo, a kind of Spanish duende on two wheels, an unexplainable (and wildly unpredictable) gift.

Isaac del Toro is the El Torito, the little bull. Or, as Velo’s Jim Cotton calls him, the “Merckxian Mexican.”

Luke Lamperti is the “California Kid,” and Luke Durbridge is “Turbo Durbo.”

Some riders embrace their nicknames. Arnaud De Lie is Le Taureau de Lescheret, the bull of his hometown Lescheret, and even celebrates a victory by pointing his fingers in the shape of horns coming across the finish line.

Among today’s racing generation, perhaps 2023 Vuelta a España winner Sepp Kuss has the best collection of modern nicknames.

The popular American rider is simultaneously known as the Colorado Kid, the Eagle from Durango, or, in what’s one of the best recent nicknames, GC Kuss. And, as his teammates call him, Seppie.

We can do better than Pogi and MVDP

Pogačar and Van der Poel need some better nicknames. (Photo: Jeff Pachoud/Getty Images )

Pogačar and Van der Poel need some better nicknames. (Photo: Jeff Pachoud/Getty Images )

So that brings us full circle to today’s unimaginative and — let’s face it — bland nicknames.

And that’s a shame because this generation is perhaps the most exciting, potent, and credible in decades.

They all deserve a proper modern moniker worthy of their genre-busting palmarès to call their own.

The Cycling Podcast has trialed “SlovAlien” for Tadej Pogačar or “Ving the Merciless” for Jonas Vingegaard, but neither of them has exactly gone viral.

Could Pogačar be the “Velvet Hammer,” because he makes it look so easy when he’s pounding everyone? The “Lynx from Ljubljana”? Hmm, maybe not. PogaStar. The “21st Century GOAT,” anyone?

In an earlier time, Vingegaard surely would have been the “Fishmonger from Hillerslev.” Today, the Danes call him the Suset fra Limfjorden, or The Rush of the Limfjord. “Vingo” just rings flat for the Pogi-Slayer.

What do we call Remco Evenepoel? He’s already called the “Aero Bullet.” What about Le Petit Cannibal? RemGo? Pelé of the Peloton?

Pauline Ferrand-Prévot is simply PFP. It works — and it’s easier to write — but what about La Reine Pauline, Queen Pauline?

There’s untapped potential for Demi Vollering, a Demi-god, for sure.

Mathieu van der Poel — today’s multi-discipline maestro — could be Mathieu van der Multi-Poel. Hmm, maybe.

So help us out. What would you call Primož Roglič?

It seems like he deserves so much more than Rogla, a rider who brings one of the most interesting backstories in cycling. Remember, he used to be a ski jumper!

The Flying Slovene or the Planica Prince. Free-flow Primož?

Ufff, no one ever said this was easy. Maybe Rogla isn’t so bad after all.