Char K., 28, had dreamed about LASIK since she was a kid. Her high school biology teacher mentioned that it was “the best decision he ever made for himself,” and after hearing more and more positive reviews over the years, she scheduled her own consultation. She finally got the surgery in June 2023.

She had good reason to turn to LASIK. Her glasses were so thick that she’d get headaches from wearing them, and she often couldn’t find frames that would work with her prescription. But it was also the little things that drew her to take a laser to both eyes: seeing clearly in the shower, being able to exercise without her heavy frames slipping down, traveling without worrying about eye care. “It’s not just about getting rid of glasses; it’s about being able to do things you couldn’t really do before,” Char says.

For people who have worn glasses or contacts their whole lives, the allure of LASIK eye surgery is strong. A quick operation—we’re talking less than 30 minutes—with minimal recovery time that gives you 20/20 vision sounds like a dream come true, especially if you wake up every morning to feel around for your glasses before you can read the clock.

The problem: LASIK is far from as simple or safe—or even as effective—as it’s made out to be.

Char and a large percentage of the nearly 800,000 people in the U.S. who get LASIK each year have learned that the hard way. Since her surgery, she has dealt with severe nerve pain, dry eye, and visual distortions—and she’s still in glasses. Contrary to what Char believed, the surgery is inherently damaging to the eye, says Cynthia MacKay, MD, an ophthalmologist and eye surgeon—and, therefore, anyone who gets it done is at risk of having it go wrong.

An Approval Process Based On Shaky Science

An Approval Process Based On Shaky Science

LASIK is marketed as a miracle cure for vision problems. But behind the glossy promises lies a billion-dollar industry built on questionable research and incomplete information.

The surgeons who perform LASIK often tout a customer satisfaction percentage rate in the high 90s and a complication rate of less than 1 percent, backed by an FDA survey. “That’s less than 1 percent of anything—infection, dry eye pain, halos—it’s an all-in risk of less than 1 percent,” says Ashley Brissette, MD, an ophthalmologist who performs LASIK and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. “There [are] very, very few surgeries that can quote that same level of complication.”

Other experts who have reviewed the research on LASIK complications—beginning all the way back in the late 1990s, when it was first put on the market, until now—suggest bad outcomes happen at a rate closer to 30 percent or higher. Among those experts is the FDA regulator who initially helped get LASIK on the market, Morris Waxler, PhD.

Waxler was the branch chief of the FDA who oversaw the approval of LASIK back in 1999. Most recently, in 2022, the FDA proposed new draft guidance for manufacturers, in part because of “concerns that some patients are not receiving and/or understanding information regarding the benefits and risks of LASIK devices.” Years later, the draft guidance still hasn’t been implemented, partly due to protests from LASIK surgeons, alleges Waxler. “It’s a dishonest enterprise,” he claims.

From Waxler’s perspective, the data that originally got LASIK approved was based on weak science. Regulators had incomplete information, and, most importantly, the approval process didn’t involve patients directly, he says. The studies were also too short in duration and only followed up with patients at 12 months post-op, which means they weren’t able to capture the long-term effects of the surgery or the rate of regression. (It’s a problem that persists today. The FDA survey that yielded a complication rate of less than 1 percent? It checked in with patients at one, three, and six months.)

Related Stories

Getting LASIK approved by the FDA wasn’t as rigorous a process as one might assume. “It’s not like a typical clinical trial,” Waxler says. When going to the FDA for approval, presenters have more control over how a study is designed and the information they share with regulators. Plus, since surgeons already had access to lasers for other eye surgeries, LASIK was being performed illegally, so the FDA was incentivized to approve the procedure quickly so it could be regulated.

It wasn’t until after Waxler retired from his position at the FDA in the early 2000s and received a call from Paula Cofer, who was dealing with LASIK complications of her own, that he realized there was more to the industry than meets the eye. The “pain, suffering, and intractable consequences” he heard about from Cofer and other patients led him to contact his old colleagues at the FDA, but “they were very dismissive,” he says.

After talking with Cofer and other LASIK patients, Waxler changed his mind on the surgery and looked back at everything that had gone wrong in getting it on the market. He thought he got the full story when LASIK was going through the approval process. “That turned out not to be the case at all,” Waxler says.

The Hidden Risks Of LASIK

The Hidden Risks Of LASIK

So, what exactly are the dangers of LASIK and related corrective vision surgeries? The most common symptom to expect following LASIK is dry eye, which is something a performing surgeon likely wouldn’t dispute. It goes “hand in hand” with LASIK and similar procedures, says Dr. Brissette, who is also a dry eye specialist.

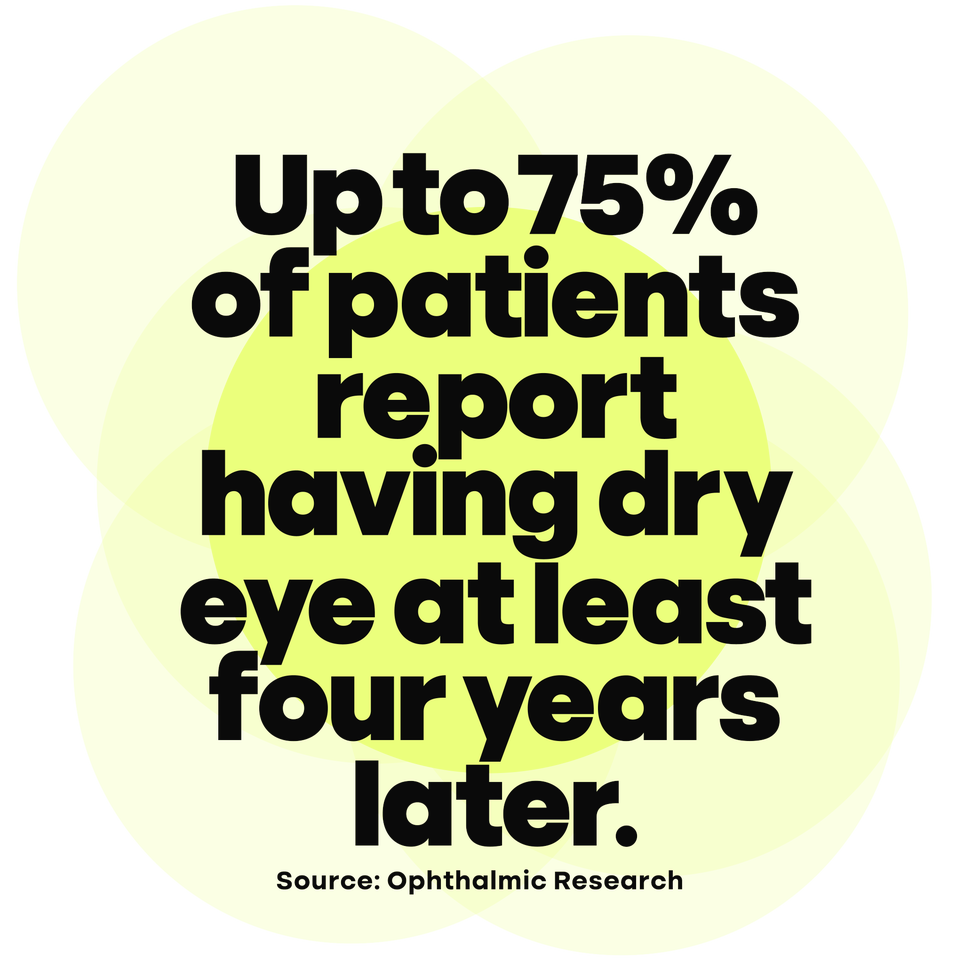

With LASIK, the number is steep: Up to 75 percent of patients complained of chronic dry eye at least four years later, according to a 2025 study in Ophthalmic Research. Dry eye after LASIK is a result of nerve damage caused by the laser, according to Pedram Hamrah, MD, a cornea specialist who treats dry eye and neuropathic pain at Tufts Medical Center. (And women tend to experience more severe dry eye symptoms, possibly due to how different hormone levels affect tear secretion, per a separate study in the Journal of Clinical Medicine.)

But sometimes the nerve damage doesn’t stop at dry eye. Between 10.5 and 13.3 percent of patients experience neuropathic corneal pain—a chronic condition in which the brain sends frequent, abnormal pain signals to the eye—one year after LASIK or similar surgeries, according to a study published this year in the British Journal of Ophthalmology. At six months, an even higher number—24 percent—of patients report experiencing ocular pain, per a recent study in Ophthalmology.

Related Stories

There’s also the potential to develop visual distortions like glare, halos, starbursts, and double vision, according to the FDA’s 2022 draft guidance, which states that 41 percent of patients experience these symptoms six months post-op. The visual distortions can be caused by scar tissue, changes in how the eye focuses when the pupils dilate in lower light, and corneal bulging. (Corneal ectasia is a type of corneal bulging, and your risk may increase if you become pregnant after getting LASIK, even years later, per a study published in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology.)

You also might notice more floaters, which occur in between 20 and 85 percent of patients, per an older study in Cornea. This could be a result of suction during the procedure.

This is another hard truth: LASIK might not work—and if it does, it might not last. In a 10-year follow-up study, researchers found that over 75 percent of LASIK customers whose myopia was corrected experienced regression of one diopter or more, according to the Korean Journal of Ophthalmology. Initially, though, over 95 percent of patients reach 20/20 vision, says Dr. Brissette. (Another thing to keep in mind: LASIK cannot stop the natural aging of the eye, which means that it won’t prevent you from needing reading glasses down the line, Dr. Brissette notes.)

Beyond the statistics, though, are real humans grappling with these effects and more.

Sarah McSwan, 45, got LASIK in both eyes in 2020. “Literally the worst decision I ever made in my entire life,” she says of going through with the surgery. Instead of getting up from the operating table with clear vision on that August day, McSwan had blurry vision and “excruciating” pain once her meds wore off, she describes.

“In the very beginning, I would walk down the hallway and the breeze would burn my eyes just from walking,” she says, adding that it felt as if there were constant smoke or sunscreen in her eyes. They burned. They itched intensely. They were gritty. Today, even after years of seeing specialists and trying new treatments, “it feels like there’s always a foreign object in them,” she says, or “like the top layer of my eyes is scorched or charred.” McSwan never achieved 20/20 vision.

On the one hand, it would make sense that LASIK and related laser eye surgeries have the potential to do some serious damage. But on the other, there are plenty of people, including celebrities like Taylor Swift, who have had the procedure and do not seem to have any problems. (Mel B and Kathy Griffin have both spoken publicly about their complications from corrective surgery.)

Ultimately, McSwan wishes she had heeded her intuition about the procedure, instead of the numerous positive stories and marketing. “I should have listened to my gut instincts, because I just had a feeling,” she says. “I didn’t think it was a good idea. Common sense told me, Why would you take a laser to a perfectly healthy cornea?”

How LASIK Works (Or Doesn’t)

How LASIK Works (Or Doesn’t)

LASIK stands for laser-assisted in-situ keratomileusis. It’s an elective procedure in which a femtosecond laser creates a flap in the top part of the eye, allowing an excimer laser to access and reshape the underlying cornea. (A misshapen cornea is a common reason people have blurry vision in the first place.)

It was developed after radial keratotomy—a procedure invented in the 1970s, in which a knife is used to carve the cornea’s shape—and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), the first cosmetic laser eye surgery approved by the FDA. In PRK, the entire outermost layer of the cornea is removed. A flap isn’t created, but the recovery is much harsher. Nowadays, you can also opt for a small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) surgery, which removes a disc-shaped lenticule from within the cornea without creating a flap.

LASIK goes like this: You get numbing drops and, depending on your doctor, a painkiller, or potentially a relaxing agent like Valium. Then, while a speculum holds your eye open to prevent blinking, a superfast laser makes the first cut to create a flap, and for a brief moment it may cause your vision to blur or to go black due to the pressure and suction caused by the tool, says Dr. Brissette. Within seconds, you should be able to see again as the doctor lifts the flap to carve and flatten (or steepen, depending on what you’re correcting) your cornea with the laser before putting the flap back in place.

The process is quick, but some find it jarring. “I didn’t feel anything, luckily, but you could smell the burning,” McSwan recalls. (Nothing is actually burning—what you’re smelling is the laser removing tissue from your eye, explains Dr. Brissette.)

Dr. MacKay was there when LASIK was first conceived by a colleague in the 1980s. “I thought he had gone out of his mind, because I knew that the cornea has the most nerves out of any part of the body, and if you cut those nerves, you’re going to get horrible pain,” she says. She also had concerns early on that shaving down and thinning the cornea could result in bulging, which would lead to distorted vision. And because LASIK also “squashes” your eye in order to cut a flap, the retina and optic nerve could be damaged, she suspected.

Unfortunately, Dr. MacKay’s predictions turned out to be right for a large group of patients. The surgery—whether it results in complications or not—is damaging to your eyes, according to Dr. MacKay. She puts it plainly: “It’s not surgery; it’s butchery.”

Joe Lingeman

Understanding The Realities Of LASIK Complications

Understanding The Realities Of LASIK Complications

In her consultations, Dr. Brissette says that glares and halos are “normal phenomena of the optics of the eye” and can occur while your eyes heal post-LASIK, but that they should resolve over time. She adds that symptoms like dry eye and visual disturbances are “part of the healing process.”

For Kirsten Martin, 37, who got LASIK in November 2022, the visual disturbances and other vision changes were so serious that she spent her first six months following the surgery “in shock,” she says. “The halos were out of control—it felt like somebody was lighting fire to the nerves between my eyes.” Martin also had persistent halos and floaters at night, which led to nightmares for the first few weeks. “It’s a lot to take in,” she says.

Her experience was a striking contrast to what she’d heard before the procedure. After her consultation, Martin was left under the impression that it was going to be “this easy surgery” and that “I was an easy candidate—that I would just be in and out.”

People who have gotten LASIK are also at risk for a flap dislocation—which could happen at any point for the rest of their lives. This is because the flap created by the laser is attached “with the strength of a contact lens,” according to Dr. MacKay. Going swimming, playing contact sports, or rubbing your eyes vigorously could potentially dislodge the flap—though Dr. Brissette says that flap dislocation occurrences are “extremely rare.” Studies say that flap displacement happens in anywhere from 1 to 8 percent of patients.

Following her LASIK surgery in January 2019, Kat Woodhouse, 57, experienced three back-to-back flap detachments in her left eye, all while her right eye was infected. “I couldn’t see anything,” she says. “I saw lights, shadows, colors, and extremely blurry shapes.”

Woodhouse couldn’t drive or work and was in “severe pain,” she says. “It felt like someone poked me in the eye with a needle.” Her eyes were extremely sensitive and couldn’t handle most light sources, from LEDs to sunlight. Eventually, she needed to get three stitches in her eye to hold the flap in place and was offered Motrin for the pain. Today, Woodhouse has cataracts, a vision-impairing condition that LASIK patients were found to develop seven years earlier than non-LASIK patients in a recent study in International Ophthalmology.

All LASIK patients also lose contrast sensitivity, which is the ability to distinguish between shades of gray, Dr. MacKay says. Their surgeons wouldn’t spot this because the main test done after LASIK—a standard vision test—asks patients to read black letters off a white background, which has a high contrast.

Related Stories

This might also explain why there’s such a discrepancy in the reported rates of happy customers, according to Dr. MacKay. “They count a complication only if the eye cannot see 20/40—not 20/20—without glasses in a room where they’re looking at a chart with straight black letters on a white background,” she explains. “You can have a patient in horrible pain, who got an infection under the flap, who’s totally disabled because of starbursts and halos and can no longer work, hates what happened, is suing the surgeon, but it’s not a complication.”

Essentially, you may not consider your laser eye surgery a success, but your surgeon might. (Dr. Brissette would not consider that example scenario a success, she says. She factors in the “complex system” that makes up vision, including how the brain and eyes work together, and overall patient satisfaction.)

Paying For The Pain

Paying For The Pain

The reality is that you probably know people who have gotten LASIK and are happy with the outcome and complaint-free. There are many who don’t experience any complications beyond, perhaps, a preliminary bout of dry eye, as well as people whose nearsightedness doesn’t regress and who wear glasses only for reading, even decades later. Dr. Brissette underwent the surgery herself while in medical school and calls it “a life-changing procedure for the right people.”

Rachel Epstein, 30, got LASIK in 2016, and she considers her surgery a success. “In the morning, I don’t have to put on my glasses to see anything,” she says. “To just open my eyes and be able to see was so magical for me to experience, and solely for that, it was so worth it.” For Epstein, all those little annoyances, like not being able to see in the morning, worrying about contacts or glasses at the beach or pool, and having to purchase contacts every month, are in her rearview.

But for the unlucky customers with complications, treating the problems can be a never-ending and costly battle. Immediately after getting LASIK in both eyes in 2019, Dawn Baldi, 43, experienced dry eye so severe that she was using over-the-counter drops every 10 minutes. “I went back to my surgeon and he just said, ‘Oh, it’ll improve. It’ll get better,’” she recalls. She returned every week and received the same message.

At the six-month mark—when her doctor was still giving her the advice to use drops—she decided to seek care elsewhere. (McSwan, Martin, and Woodhouse have all also sought care from other doctors. Char, who wished to omit her last name from this story because she still receives eye drops from her original surgeon, now gets her more intensive care and support from other doctors and specialists.)

Since her surgery, Baldi has tried multiple treatments, visiting between 8 and 10 doctors and traveling from Long Island, New York, to Boston to see Dr. Hamrah, the cornea specialist. (McSwan flies cross-country from California to see Dr. Hamrah.) She wears glasses daily to protect her eyes, does red light therapy to help with healing, and sleeps with a plastic wrap over her eyes, which she keeps sealed with a silk mask to retain as much moisture as possible. “My eyes still dry out, but it’s much worse if I don’t use both of those things,” she says.

Other common options to treat nerve pain include serum tears (made from a patient’s own blood), amniotic membrane transplants, and other anti-inflammatory therapies that can help heal the eye itself. Oral medications, including antidepressants, may address hyperactive pain signals coming from the brain, says Dr. Hamrah.

To a certain extent, dry eye is normal for up to three months following the surgery, but anything longer may need to be addressed by a specialist—and the sooner the better to prevent a chronic issue, says Dr. Hamrah. This is because the source of the nerve pain can be localized in the eye itself or, in more severe cases, a result of changes in the brain, which would require different and more complicated treatment.

Most, if not all, of these treatments are paid for out of pocket because insurance doesn’t cover complications from elective surgeries. Char and Martin both estimate that they have spent $2,000 on their LASIK complications, while McSwan estimates $12,000. Baldi guesses $15,000, and Woodhouse says she has spent tens of thousands, “and still counting,” on medical expenses, pain meds, and yearly scleral lenses, which are hard contacts that can help correct visual aberrations by basically replacing a damaged cornea, says Edward Boshnick, OD, an optometrist who specializes in fitting them.

For Woodhouse, the mental receipt doesn’t stop at what she has spent; she also thinks about the money she wasn’t able to make. After shuttering her business, Woodhouse estimates that she lost over $1 million as a result of her LASIK complications.

Explaining The Symptoms Away

Explaining The Symptoms Away

It took six months of having her pain downplayed for Baldi to seek another opinion. Dr. Hamrah notes that a regular ophthalmologist may also not be able to detect and address neurological pain, which can interfere with patients getting timely and effective treatment. The eye tests they use can’t uncover a neurological issue, and many ophthalmologists might not feel comfortable using oral medications to treat an ocular condition, he says: “This patient is basically falling through the cracks of the current system.”

McSwan, Char, Martin, and Woodhouse all report feeling rebuffed by the medical system and subsequently set adrift to find someone who could help. McSwan says that doctors tried to “explain [my pain] away and push it off.” She remembers getting into a yelling match on the phone with a doctor who told her that her issues weren’t caused by LASIK. “She tried to make it sound like my pain wasn’t that bad,” she recalls.

Char describes some of her interactions with doctors as “demoralizing, disheartening, and invalidating.” It resulted in her losing trust in them, especially after it was suggested that her severe visual disturbances existed before LASIK.

But when patients leave their doctors, they might get marked as satisfied customers, which affects the data, says Waxler. In not returning, the patients are assumed to be success stories, even if they’re about to embark on a journey riddled with specialists, pricey eye drops, distorted vision, and immense pain. Even for happy customers like Epstein, floaters and starbursts, though tolerable, are the norm—as were the prescription drops she used to treat dry eye for years following the surgery. About four years in, she also noticed her vision wasn’t as crisp as it once was, and she now wears specialized glasses at work.

Searching For True, Informed Consent

Searching For True, Informed Consent

Based on several reports, cosmetic laser eye surgeries (“cosmetic” meaning people opt for them for lifestyle reasons as opposed to treating a condition or disease) seem to have stayed consistently close to 700,000 to 800,000 per year over the past decade or so. This is down from a peak of 1.4 million surgeries in 2000. Still, the industry is expected to see about a 5 percent compound annual growth rate, according to a report from the market research firm Data Bridge. That’s an industry raking in $3.5 billion globally in 2023 and potentially $5.2 billion in 2031.

These numbers are especially concerning if word about what it’s like to live with the complications of LASIK, SMILE, and PRK doesn’t get out, say the people who have had it go wrong.

Dr. MacKay, Dr. Boshnick, and Waxler all believe that doctors are not communicating the full extent of the risks to their patients. Some patients feel that way too. Char remembers hearing “nothing but positive stories” before her surgery. Woodhouse had a similar experience: “The only information I could find online was ‘Everything’s happy. Everything’s fine. There’s no problem,’” she says, adding, “I’m still angry about that.”

Dr. Boshnick makes his living treating people whose LASIK has gone wrong, but his hope is that the surgery becomes a thing of the past—and he’s one of a few optometrists who’s outspoken about it. “There’s a cruel, unknown underbelly of this whole universe of refractive surgery that patients aren’t aware of,” he claims, and it revolves mostly around how profitable it can be.

In Dr. Boshnick’s opinion, doctors won’t speak out about LASIK because they’re afraid of hurting relationships with surgeons. Those relationships might even be financial, he alleges. “I’ve been approached by [LASIK surgeons] who tell me, ‘Look, send us the patient. After we send the patient back to you, we’ll give you $800 per eye,’ or to that effect,” he says.

Since LASIK isn’t typically covered by insurance, doctors—who can charge anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000 per eye—stand to realize quick profits from performing the surgery. But the idea that they’re doing it for the money is “silly,” says Dr. Brissette. “Nobody would’ve gone through medical school and a surgical residency and internship and fellowship to be able to perform this surgery, would’ve gone through that, to try and get rich,” she says.

Related Stories

Dr. Brissette doesn’t think patients being misled is an industry-wide concern, but rather that miscommunication or mismatching patient-doctor personalities might be at fault. “We all, as physicians, take an oath to first do no harm—that is always the goal,” she says. She adds that risks and complications come with any surgery, not just corrective eye surgery, so patients should get as much information as possible before they make their decision.

For Epstein, who wasn’t fully aware of the risks before her surgery, knowing the potential complications would have affected her decision-making process. “I would’ve definitely evaluated a little bit more, but I think I still would have made the same decision,” she says.

Life After LASIK

Life After LASIK

Between the pain, vision changes, doctor’s visits, eye drops, and scleral lenses, life after LASIK can change dramatically. “I feel like I’m a pretty different person,” Martin says. “I’ve just been in survival mode a lot.”

For Martin, LASIK complications mean that she can’t go to festivals anymore; her eyes just can’t handle the lights. She also can’t enjoy Christmas lights or go to friends’ houses where the lighting isn’t good for her eyes. “I have to sit with the reality that there’s a big part of my personality, my life, that I can’t participate in anymore,” says Martin, who dropped out of social work school because of her complications. “It’s caused me to have a lot of anxiety and a lot of shame and anger.”

These issues can affect families too. “We can’t really go out and do things as a family,” says Baldi. “I can’t go to [my son’s] baseball games. I can’t stand outside.” For Baldi, being able to keep up with her loved ones depends on how she’s feeling that day. Some days, she just can’t leave the house because of the pain.

Even if you are having a good day, it still might be hard to get out the door, says Woodhouse, who grew worried that she would develop a new infection, go blind again, or make her eyes worse. “I became agoraphobic,” she says. “I was actually diagnosed with PTSD, and it took about a year before I could work and drive again, and almost two years before I could leave the house without having panic attacks and without taking a bunch of antianxiety meds.”

The mental health toll is serious. It has been reported that some individuals, including Jessica Starr, Gloria McConnell, Kim Hybarger, and Ryan Kingerski, took their own lives following complications from corrective laser eye surgeries. Depression and suicide are a concern for LASIK doctors and “at the forefront of everybody’s mind,” says Dr. Brissette. “It’s extremely rare and very, very unfortunate when it happens,” she says.

“Of course it’s important, but because it’s so rare, and there’s so much good that has come from the surgery and so many lives changed for the better, I feel it still should be something that people making informed decisions [can decide] for themselves.” While studies are limited on the correlation between suicide and LASIK, available research suggests the incidence rate is 4 people per 10,000,000.

It’s a topic that came up for multiple women in this article. “I can tell you that I thought about it,” says Woodhouse. “In fact, it got to the point where one morning I woke up and decided I couldn’t do it again. I couldn’t go through another day like this.” But Woodhouse said she thought about her husband and son. “I said, ‘I can’t do that to them,’ so that’s the only reason why I’m still here,” she says.

McSwan also considered ending her life because of the “miserable pain” she was in, going as far as contacting an assisted suicide company in the Netherlands. “I seriously wanted my life to end because it was so horrible,” she says. “I still have problems, but at least they’re tolerable now.”

The Questionable Future Of LASIK

The Questionable Future Of LASIK

Over the past few years, the lesser-known dark side of cosmetic eye surgery has come to light, mostly because those living with complications are speaking up. Since the LASIK Complications Support Group on Facebook was created by Paula Cofer in 2014, it has grown to 8,000 members, many of whom volunteered to speak for this article or take to social media themselves to share their stories.

In 2024, Waxler (with contributions from Dr. MacKay, Dr. Boshnick, and Cofer) published a book, The Unsightly Truth of Laser Vision Correction: LASIK Surgery Makes Healthy Eyes Sick, to deter more people from getting the surgery. Dana Conroy, a filmmaker who experienced LASIK complications, directed a documentary about it, Broken Eyes, in the same year.

Serious and severe complications post-LASIK are possible, and they happen more commonly than is let on. “The people who are affected are not just dissatisfied crackpots,” says Dr. Boshnick. “This is a legitimate disaster.”

As for the people living through that disaster, they’re all trying to find ways to manage their complications and improve their vision. McSwan has been able to get her pain to a better place (though it’s still very much there), but Baldi’s remains severe. Woodhouse sees three of everything, and “that’s permanent,” she says. Martin’s vision is still off, but her brain is learning how to cope with it.

“I have hope that long-term, if my nerves heal properly—which they’ve started to—that the chronic daily pain will decrease,” says Char. “But it’s also uncertain.” She’s currently deciding between another surgery to help correct a visual issue in her left eye and using cognitive behavioral therapy to live with it. It’s hard to sign on to another eye operation after one already went wrong, and she’s worried about causing additional nerve pain. If, or hopefully when, her nerve pain improves, Char plans to use scleral lenses to address the visual aberrations she hasn’t been able to treat yet. They won’t be able to fix all of her vision issues—like the diagonal streaking pattern she gets in her left eye—but they can temper some of the other disturbances.

And though the FDA drafted updated guidance in 2022, it has not made any changes to how the LASIK industry is regulated, even after similar stories were told during hearings. But ask the man who helped get it on the market in the first place, and his thoughts are clear: “I wish it would just go out of business,” says Waxler. “My guess is it will.”

Olivia Luppino is an editorial assistant at Women’s Health. She spends most of her time interviewing expert sources about the latest fitness trends, nutrition tips, and practical advice for living a healthier life. Olivia previously wrote for New York Magazine’s The Cut, PS (formerly POPSUGAR), and Salon, where she also did on-camera interviews with celebrity guests. She’s currently training for the New York City marathon.