Participant demographics

Eighteen participants completed the PAS and IIQ surveys and participated in interviews. Table 1 lists participant demographic and genetic testing information. Participants ranged in age from 10 to 19 years (median: 15.5 years; IQR: 13.75–17 years). At the time of the study, all participants had a clinically confirmed diagnosis of a genetic condition and 15/18 had a confirmed molecular genetic diagnosis. Two participants were siblings with all remaining adolescents being unrelated to any other study participants. There was extensive heterogeneity in terms of the genetic conditions that were represented: all participants had distinct conditions apart from two unrelated adolescents with the same microdeletion syndrome and the two siblings with the same cardiac condition. With respect to cognition, 13/18 were typical (i.e., their ability to think and reason was aligned with what is typical for their age). Of five adolescents who opted to have a caregiver/parent present for their interview; 3 had atypical cognition and 2 had typical cognition.

Table 1 Participant demographics and genetic testing information (n = 18)PAS and IIQ outcomes

Overall, study participants had a mean total PAS of 3.07 ± 0.84 (range: 1.55–4.42) indicative of adequate adaptation at the time of survey completion. A combined mean score for the maladaptive component of the IIQ (rejection and engulfment) among the group was 2.85 ± 0.99 and the adaptive component (acceptance and enrichment) was slightly higher at 3.10 ± 1.06. PAS and IIQ sub-scale outcomes and internal reliability scores are summarized in Table 2. Densities and distributions of both the PAS and IIQ outcomes can be found in Fig. A1 (Additional File). We did not discern any consistent patterns with respect to the interacting components of the conceptual model and participant ages or types of conditions.

Table 2 Psychological adaptation scale (PAS) and illness identity questionnaire (IIQ) mean sub-scale and internal validity outcomesFig. 1

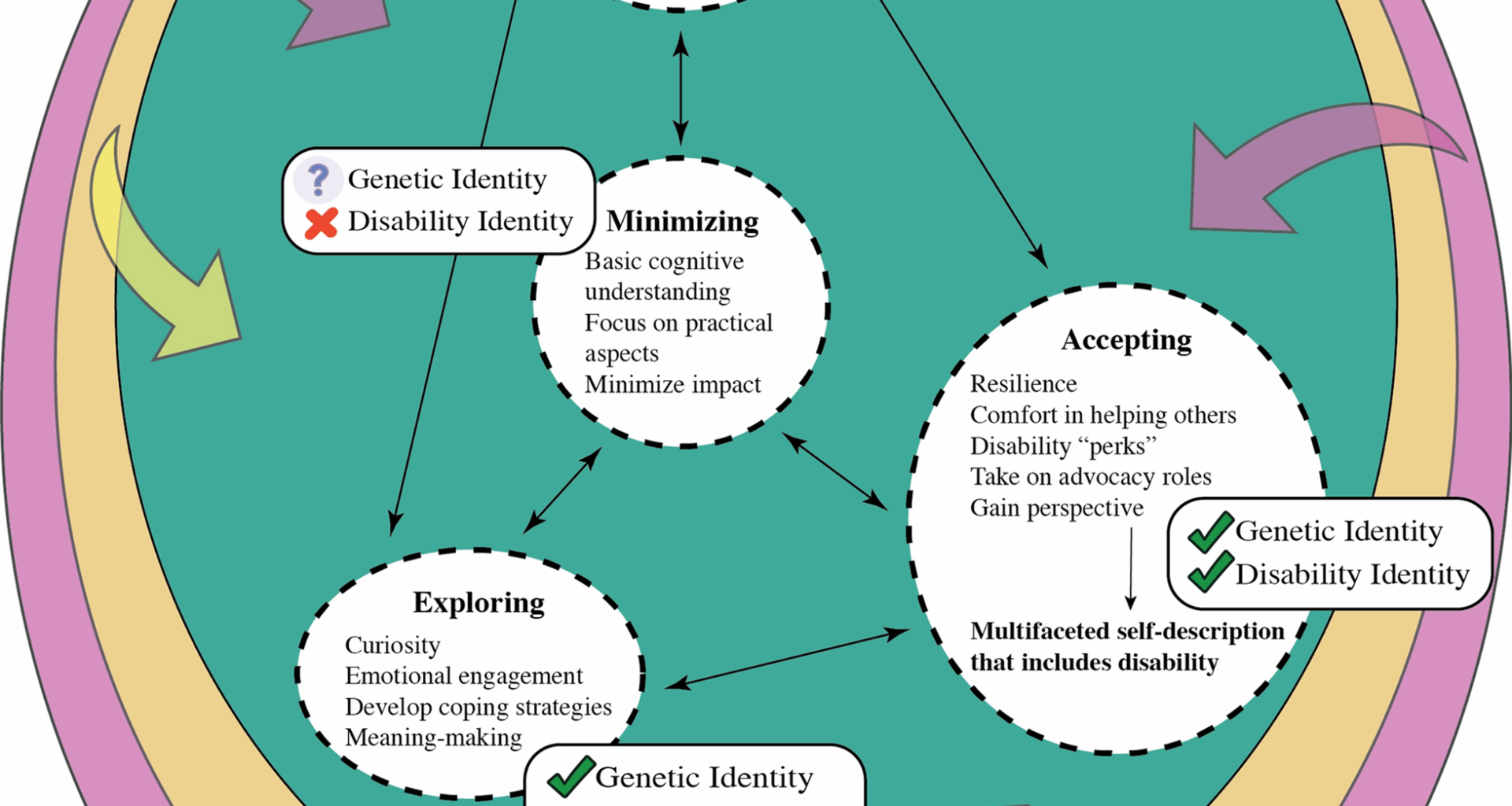

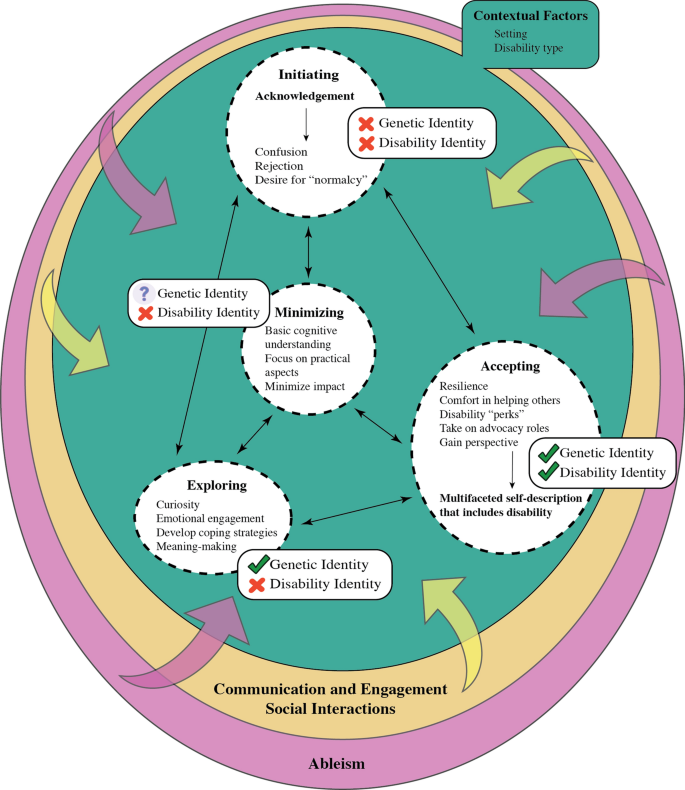

Conceptual model of genetic and disability identity development and psychological adaptation in adolescents with genetic conditions

Conceptual model of genetic and disability identity development and psychological adaptation

Our conceptual model (Fig. 1; Table 3) describes identity development and psychological adaptation which the adolescents with genetic conditions in our study experience. With respect to identity development, the model incorporates both identity as a person with a genetic condition and disability identity. For the sake of brevity, this is referred to as “genetic and disability identity development”. We have organized our conceptual model into three key components, (i) internalizing processes of genetic and disability identity development and psychological adaptation, (ii) variability that arises because of contextual factors, and (iii) external factors associated with these processes. We understand ‘genetic identity’ as the integrative process of incorporating genetic information into one’s ongoing life, and to construct a coherent, meaningful sense of oneself [55]. Disability identity can be described as “a sense of self that includes one’s disability and feelings of connection to, or solidarity with the disability community” [56].

Table 3 Representative quotations reflecting the conceptual model of genetic and disability identity development and psychological adaptation in adolescents with genetic conditionsInternalizing processes

We define internalizing processes as those with which adolescents consciously or subconsciously engaged in making sense of or developing their identities. Genetic and disability identity development and psychological adaptation in adolescents with genetic conditions generally followed pathways among four processes: initiating, minimizing, exploring, and accepting (Fig. 1). Movement among these processes was reported as frequent. Therefore, although the description below details each process in apparent isolation, it is important to recognize that each adolescent may have demonstrated features of multiple processes over the course of their interviews, in addition to having broad alignment with one of the processes overall. Also, there is no hierarchy among the four internalizing processes.

Initiating

For the adolescents in our study, internalizing frequently began with an acknowledgement of some kind of difference or challenge (physical, health, or educational), which led to their being informed, usually by their parents, of a diagnosis/condition that had already been established. Others described first noticing differences and only then embarking on a path towards diagnosis. The experience of recognizing their difference/s was regularly associated with a feeling of confusion stemming from a lack of understanding. In a handful of noteworthy cases, confusion stemmed from a misalignment between their understanding of genetics/inheritance and their expectations of how the condition manifested in their families. For example, one adolescent described being confused why she was the only individual in her family who was found to have her condition even though other relatives had similar features.

Some participants felt unable to isolate a specific point at which they acknowledged their differences because they had been diagnosed at such a young age that the aspects which signified their differences felt “normal” to them. Normalizing language (“It’s always been like this”, “I’ve grown up with it”, “It’s always been a part of my life”, “I’ve had to do it for such a long time, it’s just normal now”) was frequently employed to indicate a relatively mild emotional response to their diagnosis. However, even if their disabilities manifested earlier and this sense of normalization was profound, this did not imply that adaptation existed automatically; grappling with the process of genetic and disability identity development still needed to take place.

Adolescents who tended to deny, reject completely, or feel uncertain towards disability identity and/or identity as a person with a genetic condition, exemplified those engaged in the initiating process (Fig. 1). This was described by one participant in response to being asked if she identified as a disabled person or a person with a genetic condition, “No. I think I’m just someone who has one. It’s not really part of my identity. It doesn’t affect any aspect of me.” [Rory, 15, she/her, cardiac condition].

Minimizing

Adolescents engaging in the minimizing process tended to have a basic cognitive understanding of their genetic conditions and did not demonstrate any desire or interest in obtaining further information. While some participants acknowledged that this may change in the future if their health care needs changed, others felt that this attitude would prevail regardless.

When considering the impact their diagnosis had on their lives, their focus was oriented towards the practical aspects of their conditions, and they frequently downplayed any emotional facets of their experiences. Several adolescents described either forgetting they had a condition on some days, or that they actively avoided thinking about it. Several participants engaging in this process emphasized that there were others with the same or a similar condition who experienced far more severe impacts. Even without comparison to others, there was an inclination among these participants to minimize the impact of their conditions.

Discussions around identity as a person with a genetic condition again resulted in a tendency to qualify this through comparison to those whom they perceived to have more serious conditions than their own (Fig. 1). For example, one participant shared, “I guess so, yeah. There are definitely some more serious genetic conditions that people have, but I don’t really want to be lumped into that category because I don’t think I have a serious condition. So, I would definitely involve the word, ‘mild’ in there.” [Ali, 13, she/her, cardiac condition]. The discussion of disability identity did not arise among any participants who could be categorized as engaging in the minimizing process.

Exploring

Adolescents who were engaging in the exploring process demonstrated curiosity towards learning more about their conditions and in several cases had sought out information beyond what had been offered to them by healthcare professionals or their parents. Others spoke of seeking out information (usually online) about the medical aspects of their diagnosis as well as a desire to understand the experiences of those who shared their conditions.

The exploring process was also exemplified by a greater willingness to engage with the emotions adolescents felt with respect to their genetic conditions. In many cases, this centered around their frustrations of finding the right medications, dealing with side effects, and the trauma associated with managing their conditions (needles used for blood draws or injections were a recurrent example). Several participants also shared their fears about the future, frequently in relation to their health. For other adolescents concern centered around their educational and vocational aspirations. Many adolescents engaging in the exploring process described the impact of their conditions as being a constant presence at the back of their minds.

When asked how they managed these emotions and experiences, adolescents provided examples of several coping strategies that they had developed. Prominent among these strategies was the use of distractions; siblings, friends, and sports were regularly cited as being useful distractions from these difficult emotions. Others sought emotional support more directly by addressing their feelings or concerns with their parents and occasionally, their friends. Having a sense of humor and being able to laugh about their experiences as well as reframing their situations were also mentioned. A few participants described a drastic shut down of memories about traumatic experiences in order to protect themselves.

Many adolescents engaging in this process began to attribute positive meaning to their experiences and recognized that they could hold value. For some, this value lay in the closeness their conditions generated within their families. For many, appreciation of their conditions was reflected in a desire to pursue a career in healthcare where they felt they could be of service to those who were like them.

Participants engaging in the exploring process tended to describe their identity as a person with a genetic condition as a core part of who they were, as one participant explained, “It’s a part of who I am. It makes me different from other people. But it’s not something huge that dictates my life. It just makes me do things sort of differently sometimes.” [Nasreen, 13, she/her, ophthalmological condition]. However, none of the participants who aligned with the exploring process were accepting of a disability identity (Fig. 1). Several participants qualified their responses with comparisons of their physical abilities to those whom they deemed disabled. One participant reflected, “Not really. I know I have hearing aids, but I am able to do things, so I wouldn’t necessarily call myself disabled. It depends what you mean by disabled because there’s a couple of different meanings. But I’d call myself an active person. So, I don’t think so, no.” [Adelaide, 16, she/her, microdeletion syndrome].

Accepting

Adolescents engaging in the accepting process shared examples of positive disability experiences, an indicator of adaptive genetic and disability identity development. Many adolescents described how their genetic condition had provided them with a unique ability to manage setbacks and to be resilient. Several adolescents also valued and appreciated how their own experiences could be drawn upon to be a source of comfort to others. Other positive experiences included receiving perks that would give them access to free transportation, free movie tickets, or tax benefits, as well as a plausible reason to skip school or avoid undesirable tasks. Several participants appreciated how their experiences had allowed them to gain perspectives and outlooks on life that others may not share. For example, one participant described how she was able to pay less attention to perceived trivial “high school drama” because of the maturity and perspective she had gained as a result of her disability. Adolescents engaging in the accepting process demonstrated a desire to be involved in advocacy, awareness, or education efforts.

Participants engaging in the accepting process tended to affirm both their disability identity and their identity as a person with a genetic condition (Fig. 1). For one participant, disability identity was simply described as, “Yeah, it’s just who I am.” [Ben, 17, he/him, muscular dystrophy]. Another participant reflected, “Yes, I have a genetic condition; it’s just what it is. It’s not what I am, it doesn’t define me, but it shapes me.” [Chloe, 17, she/her, ophthalmological condition]. Adolescents engaging in the accepting process also described specifically seeking out friendships with other disabled people. Ultimately, participants engaging in the accepting process were able to view themselves as being multifaceted, comfortably including their disability or genetic condition, rather than having it be a singular, defining characteristic.

Associations with PAS and IIQ

Although all participants engaged with all the internalizing processes over the course of their interviews, we interpreted a dominant engagement with one process for each participant based on the overall impression of their interviews (i.e., the process to which they showed the greatest overall alignment). This was primarily based on TW’s careful review of their complete transcripts and collaborative discussions with the core research team. These assignments were mapped against their PAS and IIQ scores (see Additional File). Kruskal Wallis testing revealed that there were statistically significant differences among the assigned processes for the coping efficacy (H = 8.076, p = 0.044) and social integration (H = 8.237, p = 0.041) sub-scales of the PAS instrument. Analysis of the total mean PAS scores according to internalizing process approached statistical significance (H = 7.767, p = 0.051). For the IIQ instrument, the engulfment sub-scale was the only source of statistically significant differences among the processes (H = 9.698, p = 0.021). Subsequent pairwise Wilcox tests for the sub-scales that demonstrated statistically significant differences using Kruskal Wallis testing, failed to identify differences between specific pairs of processes (see Additional File).

Contextual factors

While we were able to categorize adolescents into an overall process based on the totality of their interviews, we also noted a great deal of variability and even contradiction regarding the internalizing processes. For example, a participant described initially how he felt to be the only person in his family to have a genetic condition, “I guess kind of unique…. I’m not sure. Yeah, I guess it’s a good thing. It’s kind of hard to explain, but it’s just like, I’m the only person who has it so, I’m just kind of special like that.” Later, when discussing whether he discloses his diagnosis to his peers, he shared, “Well, I don’t really – because I’m not – I don’t really act different or feel different from everyone else. So, I basically just see myself as a normal kid.” [Greg, 15, he/him, neuromuscular condition]. This idea of feeling both unique and the same as everyone else was a common juxtaposition among many adolescents. Negotiating these contradictions was an important and necessary component of the overall progression of genetic and disability identity development. We defined two important contextual factors (Fig. 1; Table 3) that appear to influence adolescents’ fluctuating processes: their setting (i.e., location or activities), and type of disability (i.e., apparent or non-apparentFootnote 1).

Setting

Many adolescents described how their genetic conditions impacted every aspect of their life in some way, but particular settings or locations resulted in it taking on either diminished or greater prominence. One participant explained, “I sort of have a daily reminder because every day there’s stuff that is hard for me to do because of my eyes. It’s not exactly something you can just forget. But it’s not at the top of my mind every day when I wake up.” [Nasreen, 13, she/her, ophthalmological condition].

Situations in which their medical needs or challenges were highlighted tended to result in greater contemplation of their identities for many adolescents. Several participants described experiencing minor reminders when they took daily medications or needed to access health care.

Participation in extracurricular activities (especially sports) was another setting in which the significance of adolescents’ genetic conditions took on greater or lesser prominence. For some participants, these activities bolstered a sense of belonging that they did not feel elsewhere, and even felt comfortable to share their diagnoses more openly. For others, this setting served only to highlight their differences and resulted in strong feelings of exclusion.

Adolescents’ views on having a diagnosis appeared also to result in contradictory feelings according to their setting. In some locations, they were grateful to have an explanation for the challenges they had experienced or why their bodies functioned in a particular way; felt an enhanced sense of self-acceptance; and in one case felt relieved that accusations of faking symptoms for attention were proven to be unfounded. In other settings, names and labels were seen as undesirable when they served to reinforce a diagnosis as a central or defining identity.

Disability type

The extent to which an adolescent’s genetic condition was apparent to others was another important contextual factor that gave rise to variations in their internalizing processes. A few adolescents who had apparent disabilities, described making efforts to hide these differences (e.g., using hair to cover hearing aids, or wearing clothing that obscured physical differences). Others with apparent disabilities described experiencing a greater sense of belonging among similarly disabled peers.

For some adolescents with non-apparent disabilities, actively avoiding situations in which their disabilities might be exposed was important. For example, one participant described a greater sense of belonging in settings where her non-apparent disability could remain as such, compared to school where her need for accommodations made her feel exposed. Several participants described examples of forced disclosure in the context of having to explain repeated absences from school or extracurricular activities, or when they required assistance or accommodations.

External factors

The final component of our model describes external factors with which adolescents with genetic conditions engage in the development of their disability identity (Fig. 1; Table 3). There were two main themes we noted in our analysis: the first is communication and engagement with caregivers, family, peers, teachers, and healthcare professionals, including social interactions with others who have the same or a similar condition. The second is the impact of ableism. Together, these themes indicate how social experiences have a substantial influence on participants’ self-construal and how they relate to their conditions.

Communication, engagement, and social interactions

The adolescent period is marked by increased attention to and complexity of social relationships and so it is appropriate that these factors featured prominently in the way that adolescents with genetic conditions grappled with their disability identity as well.

Primary caregivers, in particular mothers, were identified as fundamental to guiding adolescents’ understanding of their conditions. Mothers were frequently called upon as sources of information about their adolescents’ diagnoses as well as sources of support and comfort. They were the bearers of adolescents’ medical histories and on occasions when they could not provide answers to questions, would facilitate access to others who could (i.e., health care professionals, or support groups). Some adolescents explained how they would rely on their mothers to communicate needs or concerns to health care professionals on their behalf. Adolescents also reflected on their mothers’ formidable advocacy on their behalf in health care and education settings. Many adolescents did not claim to have experienced any differential treatment as a consequence of their diagnosis. However, when they did, it was frequently framed as a feeling of over-protection from their caregivers and noticeable to them in comparison to their siblings, other similar-aged peers, or for those who were diagnosed at older ages- before and after diagnosis. Some adolescents also reported noticing different treatment compared to their siblings because of aspects unrelated to their diagnosis (e.g., gender, age, birth order, and culture).

Most of the adolescents in our study reported an open style of communication within their nuclear families and consequently, their siblings were aware of their diagnoses and regularly cited as sources of support and distraction. Their relationships with their unaffected siblings were frequently perceived as being typical for any siblings regardless of the presence or absence of a genetic condition (e.g., “we would fight a lot but that’s normal brother and sister stuff.” [Alex, 19, she/her, nervous system condition]). One point of departure, however, were the few adolescents who described a desire to protect their unaffected siblings from the full reality of their diagnosis. In one conversation, an adolescent shared, “well, he [brother] worries quite a lot about me.” [Maya, 15, she/her, neurological condition]. When asked if this resulted in her choosing not to share her concerns with him, she agreed. Another adolescent described not being able to discern if her feelings of protection toward her sibling could be ascribed to her diagnosis or merely the fact that she was the older sibling. In cases where their siblings had been diagnosed with the same condition, older adolescents described taking on a guidance and education role.

Healthcare professionals were viewed as another important and trustworthy source of information about their genetic conditions, developing a sufficiently robust care relationship that adolescents felt comfortable to reach out to them directly to obtain information. Many reflected being particularly appreciative of those who offered comprehensive information about their condition in a transparent manner (including negative or painful aspects). Others stated a preference for being told information appropriate to their current needs and development, and introducing new information as it was likely to become relevant. Although less common, some participants described frustration at not being given sufficient details or not fully understanding the information that was provided. Few adolescents volunteered information about their experiences with genetics health care professionals; most recalled some details (e.g., genetic testing, the need for a blood draw, explanations of inheritance, or risk information) only when prompted. They attributed this challenge in recall to these interactions having happened a long time ago, having learned this information once they were older (from their mothers), or tacitly through other experiences within their healthcare journeys.

Few adolescents in our study described engaging with peers who had the same or a similar genetic condition. Of those who did, these interactions took place in the context of a condition-specific support group or organization and were motivated by a desire to find others who could relate to their experiences Others commented on how their participation in such groups allowed them to feel more easily understood compared to environments (like school) in which they were frequently the only person with an apparent difference; helped combat feelings of loneliness; served as a useful and reliable source of condition-related information; gave them a greater appreciation of the variability in experiences among those who had the same condition; and ultimately allowed them to interact with others like themselves. More participants spoke about their experiences interacting with peers who had disabilities or medical complexities that differed from their own (within their extended families, in other social contexts, and within the healthcare setting). Many of the benefits derived from condition-specific support groups could be found in engaging with others who had medical complexity, even though they arose from different etiologies.

We did not discern any noteworthy differences in opinions about support group involvement among participants who were the only individual in their family to have been diagnosed with a genetic condition and those who shared their diagnosis with other family members. There was marked variation with respect to adolescents’ sense of belonging as it related to participating in a support group: some described having no such feeling of belonging, others felt that it equaled their sense of belonging in groups with their nondisabled peers (especially sports teams), and yet others exclusively felt a sense of belonging in this setting.

Among those participants who had not interacted with a support group for their condition, some indicated they would be interested in doing so. They appreciated that this type of engagement would be a valuable experience, provide them with opportunities to learn more about themselves through hearing about others’ experiences, and feel understood. Despite their interest in participating, some adolescents perceived that the rarity of their conditions might be a considerable obstacle in finding an appropriate support group. The remaining participants who had not previously interacted with peers who had the same or a similar condition reported being uninterested or ambivalent about doing so. Interestingly, among this group, most explained that they felt their condition had minimal or very mild impacts on them.

Ableism

The entire process of identity development and adaptation in adolescents with genetic conditions occurs against the pervasive backdrop of ableism in our society. Frequently discussed by our participants were their experiences of bullying, a manifestation of ableism that is prominent in the adolescent period. For example, one participant described, “When I was in cheerleading, we wore really short shorts. There were girls who were like, ‘oh, we’re not going to touch her ‘cause we’re gonna get whatever she has’. So, it was really hard. I was bullied and picked on a lot.” [Alex, 17, she/her, nervous system condition]. Some adolescents described another manifestation of ableism, namely, not being believed or understood.

Many participants reflected how broad societal knowledge about genetic conditions was limited, even more so when the conditions were rare. They navigated this by providing the relevant clarifying information without waiting to be asked or comparing their condition to a more readily accessible example (e.g., Down syndrome). Poor societal knowledge was also frequently attributed to a lack of formal education about genetic conditions, such that knowledge was only gained through personal experience. Some saw this as an opportunity to increase awareness and engage in advocacy, while one participant directly ascribed this to ableism, saying, “I think it’s this stigma around being disabled. There’s almost no representation anywhere. So, people aren’t really exposed to it. So, they don’t really understand. They just think that people with disabilities are sad little people who need help.” [Chloe, 17, she/her, Ophthalmological condition]. Another participant acknowledged how the uncommon experience of seeing someone on a reality TV show who had a similar condition to hers would be of benefit to others, “Because, out of all the shows, movies, stuff that I have watched, I have never seen anybody that went through what I did. I think it would help a lot of younger kids too if they also saw it.” [Lily, 19, she/her, RASopathy].

Some participants also described being infantilized because of their condition; this seemed to be prominent among those who had apparent disabilities. For example, “Sometimes I feel people treat me like I am younger than 14. Probably because they don’t deal with many people who are like me, so they’re unsure how to act. I think they think that’s what I want.” [Aaron, 14, he/him, muscular dystrophy].