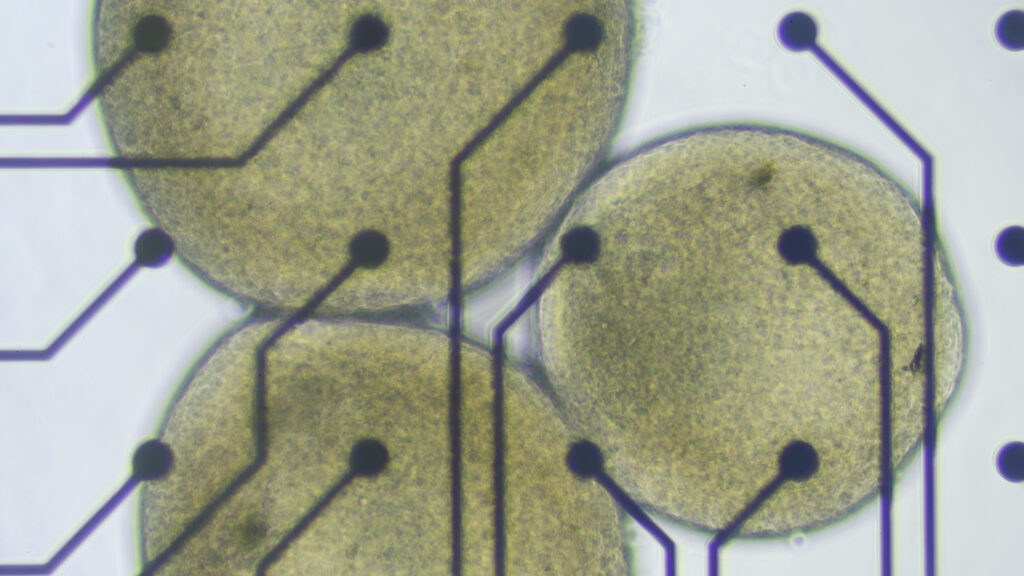

PACIFIC GROVE, Calif. — For the brain organoids in Lena Smirnova’s lab at Johns Hopkins University, there comes a time in their short lives when they must graduate from the cozy bath of the bioreactor, leave the warm salty broth behind and be plopped onto a silicon chip laced with microelectrodes. From there, these tiny white spheres of human tissue can simultaneously send and receive electrical signals that, once decoded by a computer, will show how the cells inside them are communicating with each other as they respond to their new environments.

More and more, it looks like these miniature lab-grown brain models are able to do things that resemble the biological building blocks of learning and memory. That’s what Smirnova and her colleagues reported earlier this year. It was a step toward establishing something she and her husband and collaborator, Thomas Hartung, are calling “organoid intelligence.”

They first coined the term in 2023, in a paper that argued organoids could be capable of learning, classification, and control. Organoid intelligence, they proposed, should be a new field dedicated to ethically testing those capabilities. One goal would be to better understand how the human brain works, and how its core cognitive functions change in response to drugs or toxins or a genetic mutation.

Another would be to leverage those functions to build biocomputers — organoid-machine hybrids that do the work of the systems powering today’s AI boom, but without all the environmental carnage. The idea is to harness some fraction of the human brain’s stunning information-processing superefficiencies in place of building more water-sucking, electricity-hogging, supercomputing data centers.

Despite widespread skepticism, it’s an idea that’s started to gain some traction. Both the National Science Foundation and DARPA have invested millions of dollars in organoid-based biocomputing in recent years. And there are a handful of companies claiming to have built cell-based systems already capable of some form of intelligence. But to the scientists who first forged the field of brain organoids to study psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and find new ways to treat them, this has all come as a rather unwelcome development.

At a meeting last week at the Asilomar conference center in California, researchers, ethicists, and legal experts gathered to discuss the ethical and social issues surrounding human neural organoids, which fall outside of existing regulatory structures for research on humans or animals. Much of the conversation circled around how and where the field might set limits for itself, which often came back to the question of how to tell when lab-cultured cellular constructs have started to develop sentience, consciousness, or other higher order properties widely regarded as carrying moral weight.

Intelligence is, by most accounts, further down that hierarchy (Honeybees have intelligence, as do ants and pretty much any creature with the ability to problem-solve and organize into complex societies.) But multiple scientists in attendance expressed concerns that terms like “organoid intelligence” and other claims made by biocomputing companies could cause a public backlash that might spill back onto their own work.

“Using accurate terms that neither hype nor misrepresent the work really does matter,” said Sergiu Pasca, a neural organoid researcher at Stanford University who organized the Asilomar meeting. “Overly expansive claims can confuse the public and policymakers about what these systems actually do.”

Tony Zador, a computational neuroscientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory sees efforts to produce organoid intelligence on par with silicon-based AI as a scientific dead-end. The problem, he said at the meeting in Asilomar, is that in order for data centers to work they have to do what a human tells them to do. Neural circuits, on the other hand, do what they’ve been wired up to do.

“Getting them to wire up to do what we want them to do is completely beyond what we could even conceive of right now,” Zador said. “The challenge is that we still don’t understand which neurons are important and how to form models of computation with them. Hoping that we can bypass that problem by putting them all together in a dish and reading out their activity in a way that’s useful to us is misguided.”

The fear that crystallized at Asilomar is that biocomputing may draw attention in a way that leads to overly broad laws that may hamper medical applications of organoid research. Madeline Lancaster, who developed the first brain organoids to study developmental disorders at the University of Cambridge, recently told Nature “that could bring in regulations that prevent all work, including on the side of the field that’s really doing research to try to help people.”

This kind of criticism doesn’t sit well with Smirnova, whose lab, situated within Hopkins’ Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing, has spent the better part of a decade focused on understanding how environmental toxins impact the developing human brain. When a pregnant woman is exposed to flame retardants, for example, how do those chemicals reach the fetus and interfere with the connections its growing neurons are trying to make?

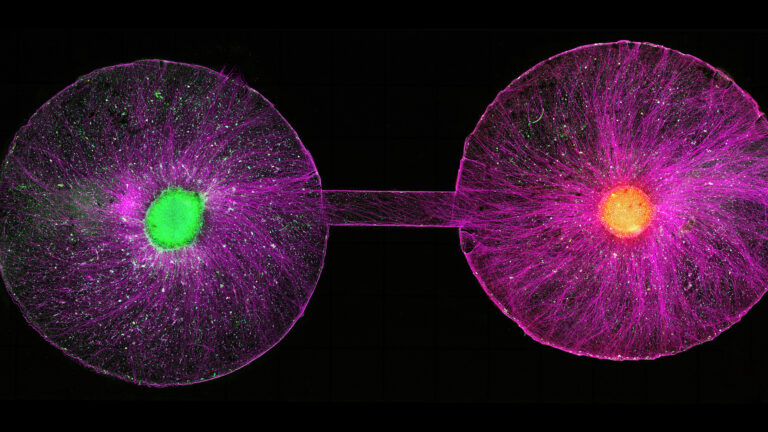

Neural organoids offered her a more powerful way to explore those kinds of questions. In the past 10 years, stem cell scientists have figured out how to make organoids representing the majority of types of cells found in the brain that can live for months, and even years, in a dish. Although still light years away from resembling anything close to the a real brain, when strung together into sausage-like strands or looped into a circuit, these “assembloids” have been shown to mimic the choreography that unfolds inside a developing nervous system as cells differentiate, migrate, and forge new connections into the pathways that control muscle contractions or sense pain.

But for them to truly supplant lab animals in toxicity studies, organoids would have to show they were capable of behavioral changes. How do you confirm an environmental exposure leads to severe autism in a clump of cells floating in a bioreactor? It’s not like you can put it in a maze and evaluate its ability to navigate new spaces. What you can do, though, is start hooking organoids up to biofabricated sensors packed with thousands of electrodes, making it possible to simultaneously stimulate and record neuronal activity at scale. That was the birth of organoid intelligence, she said in a phone interview.

“It’s a tool to study the relevant physiological functionality of these brain organoids,” said Smirnova, who didn’t attend the Asilomar meeting. “We’re not trying to create a mind in a dish.”

She also pointed out how she and her colleagues are centering questions of ethics in all the work that they do. Bioethicists were co-authors on the organoid intelligence paper. And they’re embedded in a new project Smirnova and Hartung are working on with support from the NSF to build organoids that can learn to play simple video games and guide small robots — there to monitor progress and raise red flags if they see cognitive functions emerging that are cause for concern. The couple see their work not just as an opportunity to push the boundaries of biology, but also to advance the still relatively young field of neuroethics.

The NSF sees it that way too. When it launched its “Biocomputing through EnGINeering Organoid Intelligence” program in 2024, it required applicants to have an ethicist as the co-principal investigator. During the review process, the agency also evaluated the plan for how ethics would factor into the research proposal on equal footing with the research itself. “That was very unique for the ethics and the science to be given a 50-50 split,” one person involved in the review process told STAT.

Some of the companies in this space have also been outspoken on foregrounding the ethical issues with biocomputers. But that work has gotten lost amid a more public dispute over what to call the cognitive processes that power them.

Brett Kagan is the CEO at Cortical Labs, a biocomputing startup in Melbourne, Australia that in addition to renting time on its neuron-powered computers, will also sell individuals a version of the device for $35,000 once they’ve been successfully screened for possessing the required laboratory safety and ethics approvals. In 2022, he and his colleagues at Cortical published a paper in which they showed they had taught lab-grown neurons to play the 1970s video game Pong.

Before publishing, his team had consulted with an ethicist and put the paper up on a preprint server for close to a year. Kagan said he’d done that both to be transparent and to solicit feedback from the research community about what to call this new Pong-playing power. He didn’t get much of a response, and said the scientists who did engage with it thought it was reasonable to say the neurons had acquired a kind of sentience.

But when the paper was published with “sentience” in the title, it received a wave of pushback. Writing in the journal Neuron, 30 researchers argued such language was “not justified by the data presented” and warned that describing it that way jeopardized the credibility of the field and could trigger wider restrictions on that type of work.

Kagan was initially shocked by the whole thing. But he’s come to realize it wasn’t just a reactionary flash-in-the-pan moment. Rather, it represents a foundational issue for the whole field. Which is, if they can’t decide what to call these properties of organoids, how will they know when those properties cross certain ethical lines?

“If you can’t have a shared language, the ethics don’t mean anything,” Kagan told STAT in a phone interview.

These types of growing pains are a common pitfall for emerging fields at the frontiers of science and technology. You’re not just building the plane as you’re flying it, you’re also naming all the parts and defining what they do. Trying to coordinate that type of chaos is now a top priority for Kagan. Last year he put out a call to the research community aiming to recruit at least 100 scientists from all sorts of the various disciplines that cross into the work of brain organoids and biocomputing — stem cell scientists, neuroscientists, computational biologists, physicians, ethicists, and engineers of the soft, hard, and wet varieties — into the collective effort of creating a consensus around nomenclature.

Kagan hopes that researchers like Pasca, who have previously spearheaded more narrow efforts to classify and define different types of neural organoids, will consider joining forces. “There are fair criticisms that need to be addressed,” he said. “This is a growing field and the people working in it are human. So I would encourage anyone who has criticisms to criticize, but also engage and let’s work together.”

STAT’s coverage of bioethics is supported by a grant from the Greenwall Foundation and the Boston Foundation. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.