Observations and data reduction

We utilize data from the CANUCS NIRISS GTO Program #120873, which targets five strong-lensing cluster (CLU) fields: Abell 370, MACS J0416.1-2403, MACS J0417.5-1154, MACS J1149.5+2223 (hereafter MACS1149, z = 0.543), and MACS J1423.8+240474,75. Because NIRCam and NIRISS operate in parallel, each cluster field includes both a NIRCam and a NIRISS flanking field. Our source of interest is located in the MACS1149 cluster field, which was observed with the following NIRCam filters: F090W, F115W, F150W, F200W, F277W, F356W, F410M, and F444W, each with an exposure time of 6.4 ks. To complement these observations, we also incorporate archival HST imaging from the HFF program76. The CANUCS image reduction and photometry procedures are described in detail in refs. 77,78,79,80, while the methodology for point-spread function (PSF) measurement and homogenization is presented in ref. 81. Cluster galaxies and intra-cluster light (ICL) are modeled and subtracted to prevent contamination of the photometry following82. Briefly, the NIRCam data are processed using a modified version of the Detector1Pipeline (calwebb_detector1) from the official STScI pipeline, together with the jwst_0916.pmap JWST Operational Pipeline (CRDS_CTX). The reduction steps include astrometric alignment of the JWST/NIRCam exposures to the HST/ACS reference frame, sky subtraction, and drizzling to a common pixel scale of 0.04″ using version 1.6.0 of the Grism Redshift and Line Analysis software for space-based slitless spectroscopy (Grizli;83). PSFs are empirically derived by median stacking bright, isolated, non-saturated stars, following the methodology of ref. 81, and all images are subsequently degraded to match the F444W resolution for photometry. Source detection and photometric measurements are carried out using the Photutils package84 on a χmean detection image created by combining all available NIRCam images.

First selected as a high-z double break galaxy8, our target is classified as an LRD following the criteria on UV and optical slopes and compactness given by ref. 9.

The CANUCS program also includes NIRSpec low-resolution prism multi-object spectroscopic follow-up using the Micro-Shutter Assembly (MSA85). Details of the NIRSpec processing are given in ref. 8. NIRSpec data have been reduced using the JWST pipeline for stage 1 corrections and then the msaexp86 package to create wavelength-calibrated, background-subtracted 2D spectra. A 1D spectrum is extracted from the 2D using an optimal extraction based on the source spatial profile. The redshift (and its uncertainty) of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6, z = 8.6319 ± 0.0005, was determined by performing a non-linear least-squares fit simultaneously to the Hβ, [O III]λ4960 and [O III]λ5008 emission lines. Each line was modeled with a single Gaussian and the ratio of [O III]λ4960 to [O III]λ5008 was fixed by atomic physics.

The MACS1149 cluster strong lensing model was derived using Lenstool software87 and the catalog of 91 multiple images with spectroscopic redshifts, derived from CANUCS data77. As the distance of the LRD from the cluster centre is large (approximately 3 arcmin), the contribution from the cluster lens model alone is small (μ = 1.060 ± 0.003). However, the LRD is only 0.54 arcsec away from a foreground galaxy 5112688 at photometric redshift \({z}_{{{{\rm{phot}}}}}=0.4{9}_{-0.07}^{+0.05}\) and stellar mass \(\log ({M}_{*}/{M}_{\odot })=8.0\pm 0.1\) (derived with DenseBasis,88). We evaluated the combined magnification in two ways. First, we constructed a Lenstool model containing the cluster model and the foreground galaxy at cluster redshift z = 0.54 (we verified that using a slightly lower photometric redshift for the galaxy did not affect the results). We modeled the foreground galaxy as a singular isothermal sphere, where the integrated velocity dispersion (\(\sigma=4{0}_{-2}^{+4}\,{{{\rm{km}}}}\,{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)) was derived from \(\log {M}_{*}\) and the stellar mass Tully-Fisher relation89. We find that the combined model still yields only a low magnification of \(\mu=1.1{3}_{-0.01}^{+0.02}\). Alternatively, we computed the magnification by modeling the galaxy as a dual pseudo-isothermal ellipse90, following the scaling relations of other cluster members and by using its F160W magnitude of 25.28 ± 0.03 (we verified that the magnitude uncertainty has a negligible impact on magnification). The scaling relations for parameters were constrained with Lenstool in the inner cluster regions. This method gives a more modest total magnification of \(\mu=1.06{6}_{-0.002}^{+0.004}\). We take the latter value as our best magnification estimate \(\mu=1.0{7}_{-0.01}^{+0.08}\). Considering that the uncertainty derived from different estimates is small, we correct masses, luminosities, and sizes presented in this work for CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 for a constant μ = 1.07.

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the photometry of our target in 10 bands. We fit CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 with Galfit91 and confirm that it is spatially unresolved in all filters (see Supplementary Fig. 1). From Galfit modeling, the object is consistent with a point source in all observed NIRCam filters. We perform a more refined fit accounting for the effect of gravitational lensing with Lenstruction92,93,94 to place a more stringent limit on the physical size. Lenstruction performs forward modeling accounting for lensing and the instrumental point spread function. We use lensing maps from the main cluster model, which yields a conservative magnification estimate of μ = 1.056, and we choose a clear single star as PSF reference. We use 20 mas image in the F150W filter as this filter comes with the smallest PSF size while still retaining enough flux. The half-light radius of the object results to be smaller than <0.015 arcsec with 95% confidence. This corresponds to an upper limit on the physical half-light radius of 70 pc.

Continuum and emission line fitting

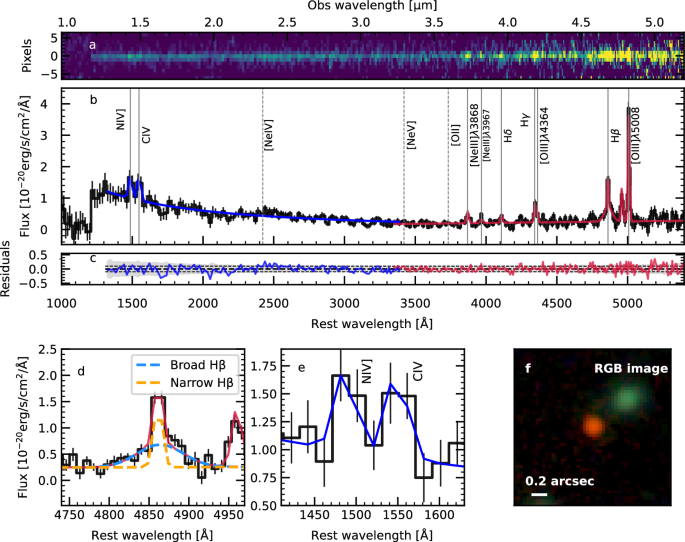

The emission lines are fitted to the 1D spectrum of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 using single or multiple Gaussian components (see below for details). LRDs often have a characteristic continuum shape, with a blue colour in the rest-frame UV and red in the rest-frame optical. This is why we split the continuum emission of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 into two parts modeled by two independent power laws. In particular, we divide the spectrum in two parts visually setting λrest,sep = 3400 Å, wavelength at which the continuum slope changes sign. Any choice for λrest,sep in the range 3300–3600 Å led to perfectly consistent results. Although our spectrum does not display a prominent break at this location, we note that the wavelength at which our spectrum changes slope is similar to that of breaks observed in other LRDs4,36 which have been interpreted as Balmer breaks. We discuss a possible physical interpretation of the spectral shape in Section “Spectral energy distribution fitting”. We fit the two parts (UV and optical) of the spectrum separately (see Fig. 1). The spectrum is fitted, accounting for the well-known variation of prism resolution with wavelength (see below).

The continuum shows the typical V-shape, having βopt = 0.96 ± 0.24 in the optical and βUV = −1.7 ± 0.1 in the UV regime, which is in line with the spectral shape of other photometric and spectroscopically confirmed LRDs9,24. No Lyman-α emission has been detected, and the shape of the spectrum around Lyman-α seems to indicate the presence of a damping wing25,26,27. The analysis of Lyman-α damping wing is beyond the scope of this paper. Therefore, we exclude the part of the spectrum with λrest < 1320 Å, avoiding any contamination from a possible damping wing given the damping wing’s size commonly found in the literature (about 2000–3000 km s−1, see e.g., refs. 95,96). Above λrest = 1320 Å, any detected emission line has been modeled with a single or multiple Gaussian components in case of line blending or broad emission.

The [OIII]λλ4959,5007 doublet is modeled by fixing the ratio between the peak fluxes (peak[O III]λ4959/peak[O III]λ5007 = 0.335) and the rest-frame wavelength separation (Δλ = 47.94 Å) of the two lines, while assuming the same FWHM for both components. Similarly, the [Ne III]λ3869 and [Ne III]λ3967 doublet is fitted by adopting a fixed flux ratio of 0.301 between the latter and the former, and a rest-frame wavelength separation of 98.73 Å, again using a common FWHM for both lines. These constraints reduce the number of free parameters for each of the [O III] and [Ne III]λ3869 doublets to three. Given the prism resolution, the [Ne III]λ3869 line remains blended with Hζ, Hη, and He Iλ3889 (see the following section).

Apart from these two doublets, there are six other emission lines detected: N iv], C iv, Hδ, Hγ, [O III]λ4368, and Hβ. Each emission line is fitted with a single Gaussian, with the only exception of Hβ, which shows signatures of a broad emission (see Supplementary Table 1). When trying to fit Hβ with one single Gaussian component, the resulting σHβ is greater than σ[O III]λ5008 by more than 7%, which is the expected difference due to the poorer spectral resolution at λHβ. Even though Fe emission can affect the Hβ region, we did not consider Fe features impactful for our analysis for two main reasons: (1) low-luminosity AGNs, including LRD AGNs, do not show evidences of FeII bump or Fe enhancement neither individually nor in stack97, while they are seen in QSOs possibly metal rich, which is definitely not the case of our target; (2) the low spectral resolution of the prism prevents us to disentangle the possible Fe feature from both the broad and narrow Hβ components. Thus, the Hβ emission line is modeled with two Gaussians accounting for both the narrow and broad components.

For the UV part of the spectrum, we have 8 free parameters in total (i.e., peak flux, peak wavelength, and FWHM for N iv and same for C iv, power-law exponent and normalization for their underlying continuum), while for the optical part we have 24 free parameters: i.e., peak flux, peak wavelength, and FWHM for [Ne III]λ3869, [O II], Hδ, Hγ, Hβnarrow, [O III]λ5007; peak flux and FWHM for Hβbroad; peak flux and wavelength for [O III]λ4364, given that we fixed FWHM[O III]λ4364 = FWHM[O III]5008; power-law exponent and normalization for their underlying continuum. We explore the parameter space for each part of the spectrum using a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm implemented in the EMCEE package98, assuming uniform priors for the fitting parameters, considering 5 walkers per parameter and 2000 trials (the typical burn-in phase is about 200 trials). Priors on the FWHM are tight, depending on the resolution of the prism, with the exception of the FWHMbroadHβ. More precisely, the prior on the FWHM of the narrow component of every fitted emission line is set to be \({{{{\rm{FWHM}}}}}_{{{{\rm{narrowline}}}}}^{{{{\rm{prior}}}}}\in [1,2]\) spectral resolution elements. The size of the spectral resolution element at the peak wavelength of each fitted line is derived considering the well-known variation of the prism resolution with wavelength99.

We compute the integrated fluxes by integrating the best-fitting functions for each emission line. In Supplementary Table 1, we report the fluxes and widths of the fitted emission lines. Unless otherwise stated, we report the median value of the posterior, and 1σ error bars are the 16th and 84th percentiles. Upper or lower limits are given at 3σ.

Hγ and [O III]λ4364

Given the resolution of the prism, Hγ is blended with [O III]λ4364; nonetheless, a clear peak at the nominal [O III]λ4364 wavelength is observed (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we fitted the blend using two Gaussian components and the results are shown in the Supplementary Table 1 (see Fiducial). Since we detected significant broad Hβ emission, a broad Hγ component could be present along with the narrow Hγ and [O III]λ4364 emission lines. We try to evaluate its impact on our results, considering the detection of the broad Hβ emission. Hence, we re-fitted the spectrum, adding an additional Gaussian component to the Hγ-[O III]λ4364 blend with FWHMHγ = FWHMHβ, \({\lambda }_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\gamma }_{{{{\rm{broad}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}={\lambda }_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\gamma }_{{{{\rm{narrow}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}\) and the \({F}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\gamma }_{{{{\rm{broad}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}/{F}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\beta }_{{{{\rm{broad}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}\) ratio corresponding to Case B recombination (see Test 1 in Supplementary Table 1). Alternatively, we also fitted the broad Hγ component considering \({F}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\gamma }_{{{{\rm{narrow}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}/{F}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\gamma }_{{{{\rm{broad}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}={F}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\beta }_{{{{\rm{narrow}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}/{F}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}{\beta }_{{{{\rm{broad}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{peak}}}}}\) (see Test 2 in Supplementary Table 1). The spectral resolution and sensitivity of our data do not allow us to be conclusive regarding the presence of a broad Hγ component, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Even though the broad Hγ over-predicts the data at λrest ~ 4300 Å, this is within 1 − 2σ, leading to good residuals. Based on the reduced χ2 criteria, the preferred solution is the one without the broad Hγ component (Fiducial), however the other two tests give still reasonably good fits. Therefore, hereafter, we will present primarily the results of our Fiducial fit, and we will discuss the uncertainties introduced by the possible broad Hγ component using the results from Tests 1 and 2.

Dust correction

In order to estimate the electron temperature, Te, and the gas-phase metallicity (hereafter metallicity), O/H, line fluxes need to be corrected for dust reddening. We derive the nebular reddening, E(B−V)neb, using the observed ratio of H Balmer lines, Hβ and Hγ, assuming the Calzetti attenuation law100. Indeed, the attenuation curve of high-z galaxies is found to be consistent with the Calzetti law. Regarding the observed Hγ/Hβ ratio, we consider the three cases described in the previous section, depending on whether and how a broad Hγ component is included. To derive the reddening, we could have also used Hδ but, given the low S/N of this line (lower than for Hγ), we cannot evaluate the possible uncertainties introduced by the presence of a broad component. The intrinsic Balmer ratios are computed using pyneb101 assuming Te = 104 K, and ne = 103 cm−3; results remain in agreement within error bars even if considering Te = 2 × 104 K, and ne = 104 cm−3. The derived nebular reddening and dust attenuation are reported in Supplementary Table 2. We note that the negative value found for our Fiducial model suggests the presence of a broad Hγ component, which adjusts the dust attenuation to a more reasonable value (see also Section “Spectral energy distribution fitting for a comparison with the stellar AV from SED fitting”). Emission line ratios are then computed using the reddening-corrected fluxes (see Supplementary Table 2). By definition, due to the proximity of the involved lines, [O III]λ5008/Hβ, [Ne III]λ3869/[O II]3727, and C iv/N iv] show almost no dependence on the reddening correction. These are the line ratios of interest for our study. [O II]3727/Hβ shows a variation of about 0.3 dex comparing the Fiducial with Test 1/2 models (when considering a broad Hγ component).

Line blending and contamination correction

When measuring [Ne III]λ3869, we also account for the flux contributions from Hη, Hζ (λ = 3890.17 Å), and He Iλ3889, all of which are blended with [Ne III]λ3869 at the spectral resolution of the prism. We define the total blended flux as [NeIII]blend = [Ne III]λ3869 + Hζ + He Iλ3889 + Hη. To estimate the contamination from these additional lines, we proceed as follows. For Hζ and Hη, we compute the dust-corrected flux ratio Hδ/[NeIII]blend from the fiducial fit (see Supplementary Table 2), obtaining a value of \(0.6{3}_{-0.20}^{+0.28}\). Assuming the theoretical Balmer line ratios from Case B recombination with Te = 20,000 K and ne = 104 cm−3102, this implies that Hη/[Ne III]blend < 0.18 and Hζ/[Ne III]blend < 0.25. For He Iλ3889, it is not possible to estimate the contamination reliably because the He I λ5877 line, required for this calculation, is undetected in our data. Thus, we can only constrain the combined contribution of the Balmer lines, finding (Hζ + Hη)/[NeIII]blend < 0.43, which in turn implies [Ne III]λ3869/[NeIII]blend > 0.57. This represents an upper limit on the contamination, as the effect of He Iλ3889 is not included. Furthermore, using the dust-corrected fluxes derived from either Test 1 or Test 2 yields Hδ/[Ne III]blend = 0.50 ± 0.20 and 0.55 ± 0.20, corresponding to [Ne III]λ3869/[Ne III]blend > 0.66 and >0.63, respectively. Given these uncertainties, we do not apply a contamination correction to [Ne III]λ3869. However, for the fiducial case, we report the magnitude of the estimated contamination in the relevant figures.

Electron temperature and metallicity

We detect the auroral [O III]λ4364 line, which can be used together with the [O III]λ5008 to derive the electron temperature and gas-phase metallicity103,104,105. Indeed, the electron temperature, Te([OIII]), of the high-ionization O2+ zone of the nebula is computed from the dust-corrected [O III]λ4364/[O III]λ5008 ratio (hereafter RO3). In each of the three cases discussed before, we find a high RO3, possibly indicating the presence of an AGN, a powerful ionizing source. Indeed, in Supplementary Fig. 3 we compare the observed value for RO3 with models from pyneb. For the fiducial dust-corrected RO3, \({T}_{e}([{{{\rm{O}}}}{{{\rm{III}}}}])=4.{0}_{-1.2}^{+1.6}\times 1{0}^{4}\) K, higher than the temperature usually found in normal star-forming galaxies (Te([OIII]) ~1−2 × 104 K)29,106. Even when considering the presence of the broad Hγ component, Te([OIII]) is high within the uncertainty, at least >2 × 104 K. Evidently from Supplementary Fig. 3, our result is insensitive to the electron density within a range of ne = 102−104 cm−3. Using the models of ref. 107, we obtain a consistent result, having \({T}_{e}([{{{\rm{O}}}}{{{\rm{III}}}}])=3.{9}_{-1.0}^{+1.6}\times 1{0}^{4}\) K. Other extreme RO3 have been found in other galaxies at same redshift1,108,109, at z ~ 4110, and are also found in low-z Seyfert galaxies31,111,112. Moreover, such a high ratio of [O III]λ4364/Hγ as ours (\(\log ([{{{\rm{O}}}}\,{{{\rm{III}}}}]\lambda 4364/{{{\rm{H}}}}\gamma ) \sim -0.3\)) is observed in AGN113,114. This can be further seen by comparing nearby AGN and star-forming galaxies from SDSS115,116 in the[O III]λ4364/Hγ versus [O III]λ5008/[O III]λ4364 line ratio diagram, as done in ref. 21 for ZS7. In this diagram, local star-forming galaxies and AGN separate into two parallel sequences, with AGN occupying a region of higher electron temperatures and having elevated ratios of [O III]λ4364/Hγ. Indeed, our target lies at the extreme end of the AGN population, the farthest from the star-forming galaxies.

We aim to derive a first-order estimate of the metallicity of our source from the total oxygen abundance O/H = O2+/H+ + O+/H+. To compute O+/H+, Te([OII]) is required. However, none of the [O II] transitions ([O II]3727, [O II]λλ7322,7332) is or can be detected in the spectra. Therefore, we use the relation of ref. 117:

$${T}_{e}([{{{\rm{O}}}}\,{{{\rm{II}}}}])=0.7\times {T}_{e}([{{{\rm{O}}}}{{{\rm{III}}}}])+3000\,{{{\rm{K}}}},$$

(1)

where Te is the electron temperature of the species in parentheses. For our fiducial case, Te([O II]) = 3.1 × 104 K. Ionic and total oxygen abundances are computed using pyneb, assuming that all O is in either the O2+ or O+ states inside HII regions. Indeed, O3+ may be neglected considering that it is <5% of the total O even in very high-ionization systems118,119 and it is negligible given the uncertainty of our computations. The O2+/H+ ratio is derived from the dust-corrected [O III]5008/Hβ, the O+/H+ ratio from the dust-corrected [O II]3727/Hβ upper limit, and we assume the Te([OIII]), Te([O II]) derived above for the fiducial case. Given that the upper limit on [O II]3727/Hβ ratio and that the highest allowed electron temperature in Pyneb models is Te = 3 × 104 K, we can derive an upper limit on the metallicity. Indeed, O/H ratios decrease at fixed line ratios and increasing electron temperature. The inferred metallicity of our source is \(12+\log ({{{\rm{O}}}}/{{{\rm{H}}}}) < 7.9\) or \(\log (Z/{Z}_{\odot }) < -0.7\). The upper limit becomes more stringent if considering the presence of the broad Hγ component (either Test 1 or 2), having \(12+\log ({{{\rm{O}}}}/{{{\rm{H}}}}) < 6.9\) or \(\log (Z/{Z}_{\odot }) < -1.8\). As a word of caution, we mention that the possible presence of very high-density regions (\(\log ({n}_{e}) > > 4\)) have an impact on the observed flux of the [O III]λ5008 line due to the collisional de-excitation of the lower level [O III]λ5008 bearing transition38,45. However, the available data prevent us from quantifying this effect since the density distribution cannot be derived.

Additional evidence that CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 is metal-poor comes from the comparison of its position on the “OHNO” diagnostic diagram, which relates the line ratios [O III]5008/Hβ and [Ne III]λ3869/[O II]3727, with photoionization models (see Fig. 2). This diagnostic has been widely used to distinguish between star-forming galaxies and AGN, both at low and high redshift39,40,41. In the left panel of Fig. 2, we compare our measurements with several reference samples: z ~ 0 SDSS AGNs (blue colormap with contours) and galaxies (pink colormap with contours)116,120; z ~ 2 MOSDEF galaxies and AGNs (black contours)121,122; three systems at z > 6, namely SMACS 06355, 10612, and 04590 (red diamonds;42, where the left-most diamond corresponds to SMACS 06355, the type-II AGN identified by ref. 114); the type-I AGN host GS 3073 at z = 5.55 (filled pink and hollow diamonds, the latter representing the [Ne III]λ3869 flux estimated under the Case B assumption modulated by the median dust attenuation;45); the type-I AGN host ZS7 at z = 7.15 (yellow cross and diamond, depending on whether the line fluxes are derived from the BLR location or from the [O III] centroid, respectively;21); and a stack of AGNs from the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) in the range 4 < z < 11 (green diamond;123). In the right panel of Fig. 2, we overlay AGN photoionization models from ref. 11 at hydrogen densities of \(\log n[{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}^{-3}]=2.0\) (grayscale) and \(\log n[{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}^{-3}]=4.0\) (colored scale). The observed “OHNO” ratios for CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 indicate a low metallicity, pointing toward \(\log (Z/{Z}_{\odot }) < -1.0\). Moreover, our stringent lower limit on [Ne III]λ3869/[O II]3727 implies a highly ionized gas, corresponding to an ionization parameter of \(\log U \sim -1.5\), consistent with values reported for other AGN candidates at z > 81,41.

As an alternative approach, we also estimate the gas-phase metallicity directly from the fiducial dust-corrected [O III]5008/Hβ ratio using the empirical calibration presented in refs. 106,124,125, under the assumption that the narrow emission lines are dominated by star formation. This yields metallicities of \(12+\log ({{{\rm{O}}}}/H)=7.0{8}_{-0.12}^{+0.14}\) (Z−0.02Z⊙), \(12+\log ({{{\rm{O}}}}/H)=7.4{0}_{-0.11}^{+0.13}\) (Z−0.05Z⊙), and \(12+\log ({{{\rm{O}}}}/H)=7.2{8}_{-0.12}^{+0.15}\) (Z ~ 0.04Z⊙), respectively. These values are fully consistent with the results from the “OHNO” diagnostic, which indicate Z ≪ 0.1Z⊙.

C iv, N iv]λλ1483,1486, N V, and [Ne v]

High-ionization lines requiring photoionization energy >50−60 eV, such as N iv], N V, and [Ne v] are signatures of the presence of an AGN. Even though C iv is also usually associated with the presence of a central AGN15,18, it is not an unambiguous tracer of an AGN in the absence of other signatures (e.g., N iv, broad emission), since it has also been detected in some low-mass low-Z galaxies at high-z. We have clear evidence of N iv] and C iv emission, while both N V and [Ne v] remain undetected, as well as [C III]. We note, however, that the resolution of the prism does not allow us to assess the presence of N V since it is blended with the Lyα and its damping wing. In many AGNs some of these emission lines are either very weak or undetected if the S/N is not high enough126,127,128. For instance, in the type 1.8 AGN GS-3073 at z = 5.5129,130,131, the N V is five times weaker than N iv], which would be totally undetected in our spectrum. Similarly, N V is undetected in GNz-1118 and in other type 1 quasars132, while N iv] is strong. As discussed in refs. 18,132, [Ne v]/[Ne III]λ3869 can be quite low in AGNs, down to 10−2−10−4. The simultaneous detection of both C iv and N iv] in galaxies at z ~ 7 has been attributed to ionization by dense clusters of massive stars formed during an intense burst of star formation14. This interpretation is supported by high observed specific star formation rates (sSFR > 300 − 1000 Gyr−1) and large Hβ equivalent widths (EW > 400–600 Å). However, for CANUCS-LRD-z8.6, this scenario is unlikely due to its very low inferred sSFR (sSFR < 10 Gyr−1; see Section “Spectral energy distribution fitting” and Figure 18 in ref. 14), indicating that sources other than massive stars are needed to account for its strong ionization.

Given the uncertainties on the dust correction given by the possible presence of a broad Hγ component and the absence of the [O III]λ1666 emission line in the UV, we will just discuss the C iv/N iv] ratio, which is reddening insensitive, leaving aside the discussion about the C/O or N/O ratios, which would be severely affected by the uncertainties in the dust correction. Assuming that all the nitrogen is in N3+, emitted in N iv], and all the carbon in C3+, emitted in C iv, we obtain a low C iv/N iv] ratio, having dust corrected \(\log ({{{\rm{CIV}}}}/{{{\rm{NIV}}}})=0.07\pm 0.3\). Assuming a temperature of 40,000 K as derived from the [O III]λ4364/[O III]λ5008 ratio and a density of ne = 103 cm−3, we infer a carbon-over-nitrogen abundance of log(C/N)\(=-0.75\begin{array}{c}+0.05\\ -0.04\end{array}\). Such low C/N abundance ratio is similar to what was reported for some nitrogen-enriched galaxies observed at high redshift133, and aligns with abundance patterns measured for dwarf stars in local globular clusters134, possibly suggesting that material-enriched through the CNO cycle has been effectively ejected via powerful stellar winds from the outermost layers of massive stars135,136,137.

Black hole mass and bolometric luminosity of the AGN

Robust estimates of BH masses usually come from reverberation mapping studies, which unfortunately are not feasible at high-z. Therefore, the so-called single-epoch virial mass estimate of MBH is often used15,55, assuming that virial relations are still valid at high-z and considering the continuum or line luminosity and the FWHM of the broad emission lines. For this work, we use the empirically derived relation:

$$\frac{{M}_{{{{\rm{BH}}}}}}{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}_{\odot }}=\alpha {\left(\frac{{L}_{\lambda }}{1{0}^{44}{{{\rm{erg}}}}{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}}\right)}^{\beta }{\left(\frac{{{{{\rm{FWHM}}}}}_{{{{\rm{line}}}}}}{1{0}^{3}{{{\rm{km}}}}{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}}\right)}^{2},$$

(2)

where the best-fit values for the scaling parameters α, β depend on the respective emission lines and/or monochromatic luminosity Lλ chosen. For instance, considering the Hβ line one has α = (4.4 ± 0.2) × 106, β = 0.64 ± 0.2 at Lλ = LHβ or, considering the continuum luminosity at rest-frame 5100 Å, L5100Å, it is found α = (4.7 ± 0.3) × 106, β = 0.63 ± 0.06 at Lλ = λL5100 Å10. The BH masses derived from these relations can be found in Supplementary Table 3. Alternatively, we also used the relations of138, finding a systematic rise in BH mass of about 0.15−0.2 dex. These relationships are calibrated to the most updated and robust mass determinations from reverberation mapping. The majority of reverberation mapping studies have been conducted using Hβ on low-redshift AGN139,140,141,142. For high-z sources, the MgII or C iv line is often utilized. However, this involves applying additional scaling from the Hβ line to formulate the virial mass based on other lines143. These relations have been used to measure BH masses for thousands of sources with an estimated uncertainty of about factor 2–3 (i.e. dex = 0.3–0.5144), when using either Hβ or MgII. Estimates based on the high ionization C iv line are even more uncertain (>0.5 dex), as this line shows large velocity offsets, implying significant non-virialized motions145,146. Moreover, there is mounting evidence that large C iv blueshifts (>2000 km s−1) are more common at z > 6 than at lower redshifts147,148,149. Since the prism resolution of our data does not allow us to distinguish between the narrow and broad C iv component, either from the BLR or from outflows, we do not use the detected C iv emission line to infer the MBH. We report our estimate for the BH mass of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 from both Hβ and L5100 Å in Supplementary Table 3 for our fiducial fit.

From the BH mass measurements (MBH,Hβ, MBH,5100 Å), we calculate the Eddington luminosity:

$$L_{{{{{\rm{Edd}}}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}}{\beta}/5100\,{{{{\text{\AA}}}}}=1.3\times 10^{38} \left(\frac{M_{{{{{\rm{BH}}}}},{{{{\rm{H}}}}}{\beta}/5100\,{\text{\AA}}}}{M_\odot}\right) {{{{\rm{erg}}}}}\,{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}$$

(3)

We also compute the bolometric luminosity (Lbol) of the AGN using the continuum luminosity at 3000 Å and using the bolometric correction presented by ref. 150. From the LEdd and Lbol, we derive the corresponding Eddington ratios λEdd = Lbol/LEdd = 0.1. We report all our results in Supplementary Table 3. We find comparable quantities (within 0.2–0.5 dex) also for the Test 1 and Test 2 cases.

Spectral energy distribution fitting

We perform a spectro-photometric fit to the NIRCam photometry and NIRSpec spectroscopy using Bagpipes43,44 with the primary goal of determining the stellar mass for CANUCS-LRD-z8.6. There was no need to scale the spectrum to the photometry. In the Bagpipes SED fitting procedure, we fix the redshift to the spectroscopic redshift of 8.63, and we assume a double power law (DPL) star formation history (SFH), Calzetti dust attenuation curve151, and Chabrier initial mass function (IMF)152. The priors for the fitting parameters are reported in Supplementary Table 4. We fixed the ionization parameter to \(\log (U)=-1.5\), which is derived from the ‘OHNO’ diagnostic (see Section “Electron temperature and metallicity”). We also set the range of metallicity considering the highest upper limit derived from observations, Z < 0.2Z⊙ (see Section “Electron temperature and metallicity”). We checked that our results do not change when increasing the upper bound of the metallicity range up to Z = 2.5Z⊙.

We adopt a Calzetti attenuation curve in the SED fitting procedure as the dust attenuation curves of high-redshift galaxies (z > 6) are generally found to be flat and lack a prominent UV bump feature153,154. In addition to using the Calzetti standard template as our fiducial dust attenuation model, we try to fit the data with an SMC template. Moreover, we adopt a flexible analytical attenuation model153,154 to better constrain the shape of the dust attenuation curve for our object. The resulting inferred attenuation curve is Calzetti-like, though slightly shallower in the rest-frame UV. We also found that the assumed shape of the dust attenuati on curve significantly impacts the inferred V-band dust attenuation (ΔAV ~ 0.6 dex), which in turn affects fundamental galaxy properties to a lesser extent (e.g., M*, SFR, and stellar age by 0.2–0.4 dex) due to degeneracies. This is consistent with previous studies that conducted similar analysis121,153,155,156.

Alongside the DPL model, which we use as our fiducial SFH model, we also perform fits with other SFHs, including the nonparametric SFHs from ref. 88 and the Leja model with a continuity prior157, and the parametric exponentially declining SFH. We found similar results within uncertainties regardless of the SFH model choice. However, this may be an exception rather than the rule, as some studies in the literature indicate that SFH model selection can significantly impact the inferred galaxy properties153,156,157,158,159.

Firstly, we fitted the observed SED without including an AGN contribution (no-AGN run). Therefore, to allow reliable estimates of the inferred host galaxy’s properties, we subtracted from the observed spectrum the broad Hβ component, which is a clear AGN signature, using the best-fitting model shown in Figure 1. We checked that subtracting the C iv and N iv] did not change the fitting results. We did not treat the UV continuum, since the real AGN contribution in LRDs to the UV flux is still unknown, and we wanted to understand what the properties of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 would be if all the observed UV light came from stars. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the Bagpipes spectro-photometric fit in orange along with the posterior distribution of some quantities of interest and the resulting SFH. Results for the fitting parameters are reported in Supplementary Table 4. The best-fitting Bagpipes model is able to reproduce most of the shape of the observed spectrum of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6. However, it does not capture some features that can be ascribed to the presence of a powerful ionizing source: (i) the non-detection of [O II]3727 emission while a very bright [O III]λ5008 emission; (ii) the full Hγ-[O III]λ4364 flux; (iii) the red slope of the continuum in the optical regime; (iv) the C iv and N iv] emissions. Indeed, in this run of Bagpipes, the main excitement mechanism for emission lines comes from stars thus, in our case, simple stellar population (SSP) models cannot reproduce all the observed spectral features.

Consequently, we run Bagpipes including a model for AGN continuum, and broad Hβ56 (AGN run). In Bagpipes, following ref. 160, the AGN continuum emission is modeled with a broken power law, with two spectral indices (αλ, βλ) and a break at λrest = 5100 Å. The broad Hβ is modeled as a Gaussian varying normalization and velocity dispersion. From this run we get \(\log ({M}_{*}/{M}_{\odot })=9.2\pm 0.1\), and a spectral index in the UV regime of αλ ~ −2. The continuum slope in the UV is usually found to be within the (−2, 2) range of values160,161,162,163 and even though αλ ~−2 gives a good result in terms of residuals (\({\chi }_{{{{\rm{red}}}}}^{2}=2.2\)), comparable to the no-AGN case, the posterior is hitting the edge of the prior lower limits. Therefore, we performed a run with Bagpipes extending the lower range of the prior on αλ down to −4, in order to ascertain the implications on the derived properties. In this case, we get a \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{red}}}}}^{2}=2.0\), and the best fit αλ is equal to −2.9 ± 0.1. The stellar mass show an increase to \(\log ({M}_{*}/{M}_{\odot })=9.65\pm 0.1\), while the other properties still remain consistent within errorbars with the run having αλ ~ −2. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the Bagpipes spectro-photometric fit in orange along with the posterior distribution of some quantities of interest and the resulting SFH. The red continuum in the optical is captured by the best-fitting model, as well as the broad emissions. Furthermore, the [O II] emission is dimmer than in the previous run, yet it still does not align with the observed non-detection. The metallicity in both runs (w/o and with AGN) is in agreement with the observed data. The dust attenuation is about 2.2 times higher than in the previous run, causing the stellar mass to increase 0.4 dex. We did not set a tight prior on AV since the observed value is very uncertain (see Section 22 and Supplementary Table 2); indeed it is in agreement within errors with the results of both no-AGN and AGN runs, considering that \({A}_{V}=0.44{A}_{V}^{{{{\rm{neb}}}}}\) assuming a Calzetti dust law151. However, in order to compare with the results from the no-AGN run, we run Bagpipes including the AGN model as before and setting a tight Gaussian prior around the value of AV determined from the no-AGN run (AGN-tight run), and we obtained AV = 0.7 ± 0.2 and \(\log ({M}_{*}/{M}_{\odot })=9.42\pm 0.07\). Finally, the degeneracy between the AGN model, AV and M* is evident, and prevents us from obtaining a precise determination of M*. For the aim of this work, we considered the M* derived from the AGN-run as fiducial, and its error accounts for the uncertainties due to the variation of the SED model, i.e. \(\log ({M}_{*}/{M}_{\odot })=9.6{5}_{-0.44}^{+0.1}\) (corrected for magnification).

With these caveats, we propose a physical model to explain the observed properties of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 (see also and Fig. 4 for details). Our modeling of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 suggests an AGN-dominated UV continuum with minimal dust obscuration along our sight-line, while the red rest-optical continuum is likely due to dust-obscured stellar emission. Its compact size and high SFR (about 50−150 M⊙yr−1) indicate significant obscuration in stellar birth clouds. This suggests that CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 is in an evolved state that will transition toward a luminous quasar-like system at z = 6, rather than a lower-luminosity AGN at similar redshifts. Even though the run including the AGN component better reproduces the observed data, higher wavelength observations are needed to constrain the real AGN contribution to the observed multiwavelength light of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6. How best to incorporate AGN components in SED fitting for LRDs remains a topic of ongoing debate due to the inability of current data to meaningfully distinguish between different models4,47,164. In light of these uncertainties, we decided to use the stellar mass of the AGN-run and to account for the variation arising from the other models (no-AGN, AGN-tight) in the error bars.

Comparison with simulations and semi-analytical models

In this section, we investigate the possible formation channels for the massive BH powering CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 by comparing the inferred BH mass with predictions from semi-analytical models (SAM) and numerical simulations.

To get a first approximate idea about the possible growth history of the CANUCS-LRD-z8.6’s BH, we first assume that this BH has been accreting for its entire history at a fixed rate, expressed as a fraction of the Eddington rate, with a constant radiative efficiency ϵ = 0.1. As shown in Fig. 5, fixing the accretion rate to the observed value (λEdd = 0.1) requires an extremely heavy BH mass (Mseed > 3 × 107M⊙) at redshifts higher than 25. This seed mass is higher than any value predicted by theoretical models165. This implies that, at earlier epochs, the BH powering CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 must have been accreted at rates higher than the one observed at z = 8.63.

Assuming λEdd = 1 leads to a seed mass of Mseed ~ 104M⊙ at z~25 or Mseed ≳ 105M⊙ at z ~ 15. This growth path is consistent both with intermediate-mass BHs formed in dense star clusters166 and with heavy seeds predicted by the direct-collapse BH scenario60, and/or by scenarios based on primordial black holes167,168.

Assuming λEdd = 1.5, the required seed mass would be consistent with low-mass seeds (10-100 M⊙) from Pop III stellar remnants at z ≳ 20169. This argument suggests that the BH in CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 originates from heavy seeds, constantly growing at a pace close to Eddington, or from light seeds constantly growing at super-Eddington rates.

In the following, we discuss the formation channel of CANUCS-LRD-z8.6’s BH more accurately by performing a comparison with SAM predictions. Initially, we consider the results by ref. 64, hereafter C24. This model, calibrated to match the galaxy stellar mass function in the local universe, is also able to reproduce the luminosity and stellar mass functions of galaxies up to z ~ 964, and the local MBH − M* relation. The C24 models are based on the GAEA SAM [e.g.,170,171] run on merger trees extracted by using the PINOCCHIO code172, and we consider here two different seeding models: (i) Pop III.1, a scheme that allows for an early formation of massive seeds (about 105M⊙) at z ~ 25 from the collapse of Pop III protostars173; this formation mechanism is physically motivated and does not depend on the mass resolution of the simulation; (ii) All Light Seed (ALS), a model that results into seeds of 10-100 M⊙. In this model, accretion onto BHs is assumed to be Eddington-Limited. Pop III.1 stars are a subclass of Population III stars, which ref. 174 divided into two categories. Pop III.1 stars are a unique type of Population III stars that form at the centers of dark matter minihalos in the early universe (z ≳ 20), remaining isolated from any stellar or BH feedback174. In contrast, Pop III.2 stars also form within dark matter minihalos but are affected by feedback from external astrophysical sources. This external influence promotes gas fragmentation, leading to the formation of lower-mass stars compared to Pop III.1.

For the scope of this work, we compare CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 with the most massive BHs predicted by the C24 models at z ~ 8 for the two seeding prescriptions, as shown in the left panel of Supplementary Fig. 6. This comparison implies that SAMs employing Eddington-limited accretion, although successfully describing the statistical properties of galaxies and BHs from the local up to the high-z universe, fail in reproducing the most extreme BHs at high-redshift, with CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 representing one of the most extreme examples.

We further consider the results by ref. 69, which investigates the formation of massive BHs at z > 7 by means of the SAM Cosmic Archaeology Tool (CAT)68. In this work, the seeding prescription accounts for both light and heavy seeds, and the BH growth can occur in the Eddington-limited (EL) and super-Eddington (SE) regimes. As can be seen from the left panel of Supplementary Fig. 6, in the CAT framework, the EL model predicts BH masses that are consistent with GNz-11 at z ~ 10 and CEERS-1019 at z ~ 8.741, but do not exceed about 107M⊙, therefore being inconsistent with our new data. The model including SE accretion predicts several tracks that successfully assemble 108M⊙ at z = 8.669, the most massive one shown in blue in the left panel of Fig. 5. Thus, super-Eddington accretion is essential to assemble a large amount of mass within 500 Myr (see also refs. 175,176) and therefore to reproduce the CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 inferred mass.

The main caveat of SAMs is that they cannot fully capture the complex and non-linear interplay between BH accretion and feedback processes. Therefore, the growth predicted in SAMs during the SE phase might be too efficient, if compared to more sophisticated models, e.g. hydrodynamical numerical simulations. This is clearly shown by the results of refs. 177,178 that are based on numerical simulations with light seeds growing at super-Eddington pace. From refs. 177,178 results, it can be seen that early light seeds, even if accreting at super-Eddington rate, can reach a maximum mass of 105M⊙ (107M⊙) at z ~ 6, thus being unable to reproduce the BH masses estimated so far at z > 6. For this reason, most of the numerical hydro-dynamical simulations of BH formation and growth assume a heavy seed prescription (Mseed > 105M⊙) to reproduce the large masses of BHs powering z ~ 6 quasars. The accretion rate onto the BHs is modeled according to the Bondi–Hoyle–Lyttleton prescription179,180,181, with a boost factor α used as a correction factor for the spatial resolution of the gas distribution surrounding the BH.

In what follows, we separately discuss predictions from simulations that cap the BH accretion to the Eddington limit and those that allow for super-Eddington growth. In the middle panel of Supplementary Fig. 6, we report the results of EL simulations. We find that the only simulation that can reproduce the CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 BH mass is the reference run by ref. 177. Vice-versa, both ref. 72, when using the numerical recipe of the FABLE suite71, and ref. 182 predict a BH mass that is about 1 order of magnitude smaller. Interestingly, all the simulations reported in this panel, though being inconsistent with CANUCS-LRD-z8.6, are capable of reproducing AGN candidates such as GNz-11 at z~10 and CEERS-1019 at z ~ 8.741, and the estimated masses of BHs powering z~6 quasars, apart from the most extreme case of J0100+2802 (MBH ~ 1010M⊙,15). We further notice that the simulations by177 predict a BH mass at z~8 that is about 2 orders of magnitude smaller with respect to the reference run, if a radiative efficiency larger than only a factor of two is considered. This clearly shows how sensitive predictions from numerical simulations are to the feedback prescriptions implemented.

We now move to numerical simulations of heavy BH seeds’ growth, including super-Eddington accretion, shown in the right panel of Supplementary Fig. 6. First of all, we note that the reference run by ref. 72 is able to reproduce not only CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 but also z ~ 6 quasars, including the extreme case of J0100+2802. With respect to the original recipe employed in the FABLE suite (shown in the middle panel), in the reference run the authors apply the following variations: (i) reduce the halo mass where BH seeds are placed (from Mh = 5 × 1010h−1 M⊙ to Mh = × 109h−1 M⊙), effectively resulting in earlier BH seeding (from z ~ 13 to z ~ 18); (ii) reduce the overall AGN feedback; (iii) allow for mild super-Eddington accretion (λEdd = 2). All these changes promote early BH growth, which emerges as a necessary condition to explain the BH mass of early AGN and quasars. Interestingly, this simulation supports a scenario in which CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 represents a progenitor of the most massive QSOs at z > 6, such as J0100+2802.

We further notice that the run Bh22d of ref. 182 (see also the similar setup used in ref. 183) predicts a rapid mass assembly consistent with CANUCS-LRD-z8.6, if the accretion rate is boosted (λEdd = 2, α = 100) and the radiative efficiency is low (ϵ = 0.1), which in turn lowers the AGN feedback effect on the BH growth. Similarly, refs. 177,184 find the AGN feedback to be the most limiting factor in BH growth.

Notably, in ref. 177, the BH grows less in the super-Eddington regime due to the excessive feedback. However, this conclusion is sensitive to the detailed numerical implementation. Reference 185 explored the BH growth with high-resolution numerical simulations with a comprehensive model of AGN feedback in the super-Eddington regime. They find that the jet power in the super-Eddington regime is a critical factor in regulating the accretion rate onto the BH, because of its ability to remove the fueling gas, as also found in other works186. Their run with low feedback predicts a BH mass at z ~ 8.5, only a factor of about 2 smaller than CANUCS-LRD-z8.6.

We further compare model predictions with the stellar mass inferred for CANUCS. The CAT model, including SE accretion, predicts systems with black holes over-massive with respect to their host galaxy when compared to the local MBH–M* relation70. This is a consequence of a de-coupled evolution between the BH and the galaxy, triggered after short (0.5–3 Myr), (1–4%) phases of SE accretion during which the BH experiences fast growth and suppresses star formation via efficient feedback, a scenario that is also supported by recent simulations52 and observations of quiescent over-massive black holes53. Interestingly, the stellar masses predicted by CAT at z ~ 9 are consistent with the low-mass end of the estimated stellar mass for CANUCS-LRD-z8.6. Regarding numerical simulations, the reference model in ref. 177 also successfully assembles >1010M⊙ by z ~ 9, satisfying the constraints posed by CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 both in terms of black hole mass and stellar mass assembly at z = 8.6. To our knowledge, none of the other models explored in this overview are able to satisfy both constraints, although for many of them we were not able to recover the information on the stellar mass from their published works.

The comparison among results from different numerical simulations emphasizes how complex is the modeling of BH seeding, accretion rate, and AGN feedback, and how important it is to collect observational data as the one provided in this work. CANUCS-LRD-z8.6 poses significant challenges to both hydrodynamical simulations and semi-analytical models. Its existence requires rapid and efficient assembling of 108M⊙ in only 500 Myr, thus providing stringent constraints to seeding prescriptions, feedback recipes, and accretion physics modeling in theoretical models and simulations.