Pancreatitis is an acute inflammatory disease caused by premature activation of pancreatic enzymes, leading to pancreatic injury and multiple organ dysfunction. Over the past three decades, its global prevalence has continued to rise [19, 21, 23]. A recent worldwide epidemiological study highlighted alcohol consumption, obesity, and gallstone disease as major drivers, emphasizing that reducing alcohol intake is crucial for alleviating the future burden of pancreatitis [5, 24]. Against this background, our study utilized the Global Burden of Disease (GBD 2021) database to systematically evaluate the global, regional, and national burden of AAP from 1990 to 2021, with stratified analyses by sex, age, and SDI.

Compared with previous work, our study expands upon and extends existing findings. Tang et al. (2025) [6, 7]analyzed global trends of alcohol-related pancreatitis using GBD 2021 data, while our analysis advances in three key aspects. First, we employed the TMREL framework to specifically quantify the risk attributable to high alcohol intake, rather than overall alcohol use. Second, we incorporated PAFs and SEVs to characterize the preventable burden and exposure patterns across alcohol-dependence quintiles. Third, segmented regression was applied to identify nonlinear inflection points in temporal trends, complementing the age–period–cohort models used previously. Moreover, our findings revealed a widening sex disparity—particularly among younger populations—and quantified the strong positive correlation between alcohol dependence levels and PAFs.These methodological innovations provide important insights for formulating targeted public health strategies.

Overall, the evidence demonstrates a robust positive association between per capita alcohol consumption and the incidence and mortality of pancreatitis, particularly AAP. This relationship is evident both in national-level time-series data and in individual-level dose–response analyses.Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that higher total alcohol intake substantially increases the risk of both acute and chronic pancreatitis, with spirits and binge drinking being the strongest contributors [25]. Notably, women may have lower thresholds or steeper risk curves [26]. These findings are consistent with clinical observations that attacks often follow episodes of heavy drinking. In several Northern European settings, reductions in alcohol sales were accompanied by parallel declines in AAP burden, while policy interventions such as increased taxation, restricted availability, and stricter drunk-driving enforcement were shown to reduce overall consumption and related health outcomes [27, 28]. Individual-level evidence also supports these associations: a Swedish prospective cohort study reported a dose–response relationship between spirits intake and AAP risk, whereas associations with beer or wine were weaker [29]. Similarly, in the Netherlands, epidemiological data suggest that thousands of first-time alcohol-related acute pancreatitis cases occur annually, of which approximately 20% progress to severe disease with necrosis or organ failure [30], underscoring that reducing alcohol exposure remains essential even in high-income healthcare systems.Mechanistic studies further elucidate the biological pathways linking alcohol and pancreatitis. Ethanol and its metabolites (acetaldehyde, fatty acid ethyl esters) disrupt acinar cell calcium homeostasis, trigger premature zymogen activation, induce oxidative stress, and impair mitochondrial function, thereby initiating a cascade from reversible injury to necrotizing inflammation [31, 32]. Taken together, both macro-level (policy) and micro-level (biological) evidence converge on a consistent conclusion: reducing overall alcohol consumption and heavy episodic drinking is pivotal to lowering the incidence and mortality of alcohol-attributable pancreatitis.

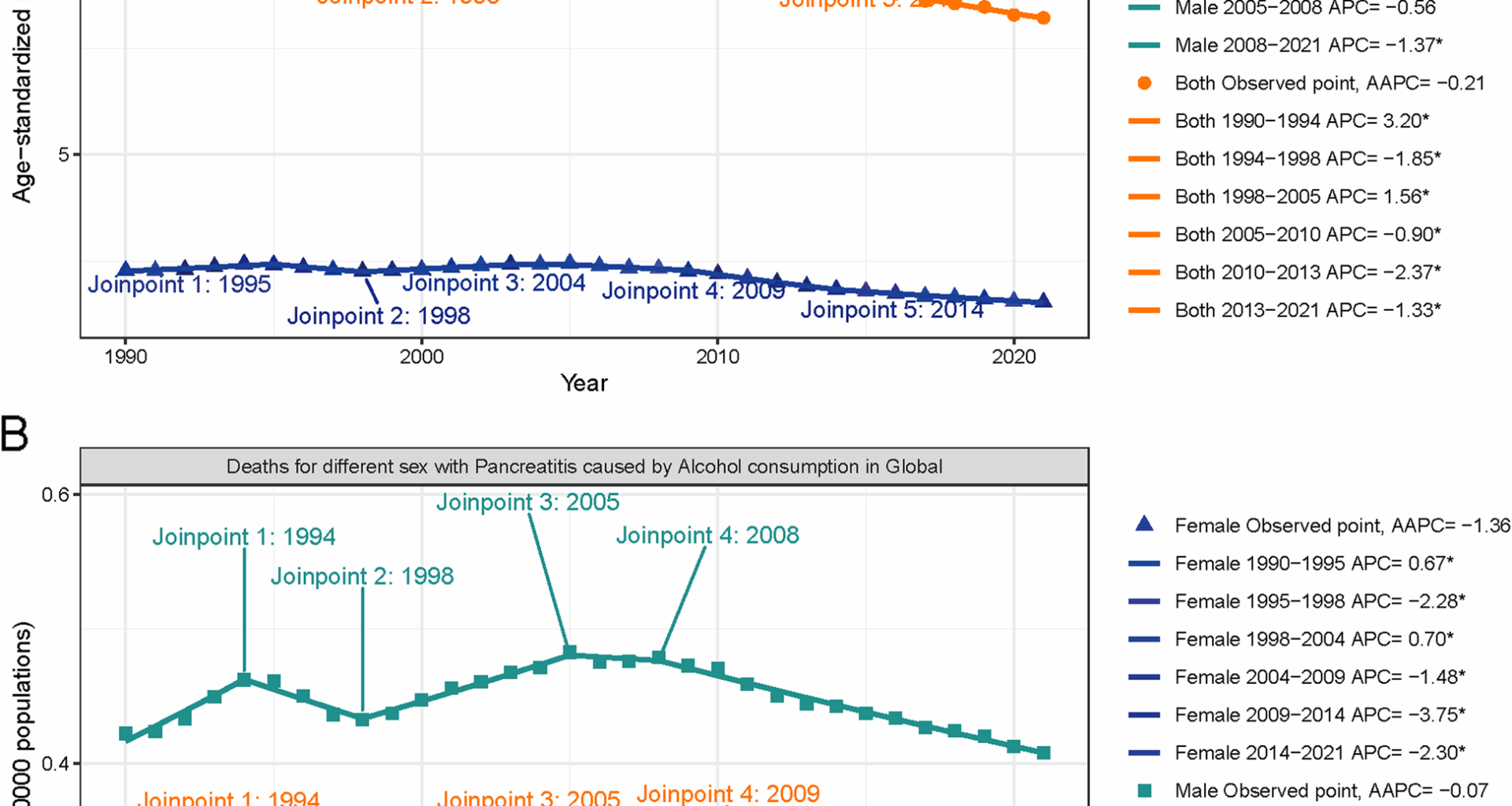

Our study revealed that although global ASDR and ASMR for AAP remained relatively stable over the past 32 years, absolute DALYs and deaths increased markedly. This indicates that population growth and aging are the main drivers of the rising disease burden. Similar trends have been reported in prior studies; for instance, Tang [6]and Li [33] highlighted that the global burden of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer has increased largely due to demographic shifts. In contrast, age-standardized rates showed minimal changes or even declines, suggesting that improvements in healthcare access and early diagnosis may have offset some of the demographic pressures. However, this “overall stability” conceals substantial regional and demographic disparities, particularly in low- and middle-SDI countries where both ASDR and ASMR continue to rise, reflecting pronounced global inequities in disease burden.

Regionally, Eastern Europe exhibited the highest ASDR and ASMR in 2021, with the most rapid growth. Evidence from multiple European countries suggests that Eastern and parts of Northern Europe have long maintained higher per capita alcohol consumption and a greater proportion of spirits, with heavy episodic drinking (HED) being more prevalent, consistent with the higher proportion of alcohol-related pancreatitis in these regions [34].A systematic review also demonstrated that alcohol-related acute pancreatitis accounts for a larger proportion of cases in Eastern/Northern Europe. In Malmö, Sweden, reductions in alcohol sales coincided with declines in alcohol-related pancreatitis and other alcohol-related harms, underscoring the policy sensitivity of alcohol availability.Beyond these localized findings, Russia [35]provides a compelling example of the impact of comprehensive alcohol control policies. Beginning in the mid-2000s, Russia implemented a series of interventions—including substantial excise taxation on spirits, restrictions on sales hours, and advertising bans—which were associated with a sharp reduction in per-capita alcohol consumption (by about 43% between 2003 and 2016) and concomitant improvements in life expectancy. These outcomes illustrate how sustained, multifaceted national strategies can rapidly mitigate alcohol-related harms.

In contrast, North Africa and the Middle East reported the lowest ASDR and ASMR globally, reflecting low alcohol accessibility and strict cultural or religious prohibitions. High-SDI countries, however, experienced overall declines, attributable to a combination of taxation and pricing strategies, restrictions on marketing and sales, drink-driving enforcement, and mature healthcare systems [36]. At the global level, the WHO’s SAFER initiative [37]—launched in 2018—offers a scalable framework of five high-impact interventions (Strengthening restrictions on alcohol availability, Advancing drink-driving countermeasures, Facilitating screening and brief interventions, Enforcing bans on alcohol marketing, and Raising prices through excise taxes).Taken together, these findings highlight the pivotal role of public health policies in shaping the burden of alcohol-attributable pancreatitis. Embedding our epidemiological results within these policy contexts underscores the urgent need for both regionally tailored interventions to reduce the preventable morbidity and mortality associated with AAP.

Sex differences emerged as another notable finding. From 1990 to 2021, males consistently had higher ASDR and ASMR for AAP compared to females, with the sex gap widening over time, particularly among individuals aged 25–44 years. Previous research consistently shows that alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis occurs more frequently in men [38]. This disparity arises from both social behaviors and biological mechanisms. Behaviorally, men have higher drinking frequency and quantity and are more prone to HED, which multiple prospective cohort and case–control studies have strongly associated with increased risk of acute pancreatitis [26]. Biologically, higher alcohol dehydrogenase activity in men accelerates ethanol metabolism but leads to rapid acetaldehyde accumulation, triggering oxidative stress, inflammatory pathway activation, and acinar cell injury [39, 40]. Conversely, estrogen has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which may partially explain lower risk in women. Moreover, men more frequently present with comorbid smoking, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, all of which act synergistically with alcohol to exacerbate pancreatic injury [41]. Epidemiological evidence further supports this pattern: in high-drinking regions such as Northern and Central Europe, the rising incidence among men has been a primary driver of overall AAP increases [42]. Additionally, women often demonstrate greater health-seeking behaviors, presenting earlier for medical care and thus receiving timelier intervention, which may shorten hospital stays and reduce mortality [43].

In the analysis of PAFs, we observed that global ASDR- and ASMR-related PAFs increased with rising SDI levels, peaking in high-SDI regions. This reflects the paradox that, despite advanced healthcare systems, high-SDI countries maintain elevated alcohol-attributable burdens due to persistently high consumption levels. According to WHO reports, per capita alcohol intake in many high-income countries exceeds 8–10 L annually, with strong cultural acceptance of drinking [44, 45]. Conversely, PAFs were lower in low-SDI regions, largely due to limited alcohol availability and lower consumption. However, low PAFs do not equate to low risk, as underdiagnosis and underreporting in resource-constrained settings may obscure the true burden [46]. Importantly, the observed “S-shaped” association between PAFs and SDI suggests that during early economic development (SDI 0.4–0.75), alcohol consumption tends to rise rapidly, while public health interventions lag behind, leading to steep increases in disease attribution [47]. At higher SDI levels, taxation, sales restrictions, and public education, combined with stronger healthcare systems, moderate this trend, explaining why PAF growth slows or declines in high-SDI countries.

Decomposition analysis Further showed that from 1990 to 2021, global DALY increases in AAP were primarily driven by population growth (+ 88.85%) and aging (+ 25.26%), while epidemiological improvements contributed − 14.11%, partially offsetting demographic pressures. This finding is consistent with broader GBD studies, which demonstrate that despite advances in healthcare, demographic changes remain the dominant driver of rising burdens in alcohol-related diseases [14]. Notably, the contribution of aging was higher in women than men (68.87% vs. 23.12%), likely reflecting longer female life expectancy and cumulative risk [48]. Women may also be biologically more susceptible to alcohol toxicity, with higher body fat content and slower ethanol metabolism contributing to greater long-term exposure risk.Regional differences were also pronounced. High-SDI countries exhibited the strongest aging-driven effects, yet al.so showed the greatest negative contributions from epidemiological improvements, reflecting the benefits of advanced healthcare systems, standardized management, and intensive care resources [34]. In contrast, in low-SDI countries, aging contributed less, but positive epidemiological contributions were observed, suggesting gradual improvements in diagnosis and treatment. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, while the absolute burden of alcohol-related disease continues to rise, recent studies suggest that better emergency care and diagnostic technologies have increased reporting of alcohol-related pancreatitis [45]. Nonetheless, these improvements remain insufficient to counterbalance population growth, underscoring the persistent gaps in healthcare capacity and alcohol regulation in low-resource settings.

Based on these findings, we propose several public health priorities. First, in low- and middle-SDI countries, stricter alcohol control measures—including taxation, restricted sales, and marketing bans—should be paired with health education targeting young adults to curb high-risk drinking [36].Second, greater investment in primary healthcare is also needed to enhance early detection and management of acute pancreatitis and to strengthen surveillance systems [44].Third, in high-SDI countries, targeted screening and interventions for individuals with alcohol dependence or chronic pancreatitis remain essential to prevent rebounds in disease burden.Clinically, our results underscore the importance of alcohol cessation counseling and relapse prevention for patients with a history of AP, given the high risk of recurrence and progression to chronic pancreatitis. The disproportionate burden in younger males highlights the need for early identification and brief interventions during gastroenterology visits. Moreover, frequent comorbidities such as diabetes, liver disease, and malnutrition warrant integrated screening and management to improve long-term outcomes.Finally, international collaboration remains vital. By combining evidence-based alcohol policies with clinical prevention and comprehensive care, the global burden of alcohol-attributable pancreatitis can be substantially reduced [47].

This study has several Limitations. It relies on GBD 2021 estimates, which vary in quality across regions; underreporting, data sparsity, and ICD coding variability, especially in low- and middle-income countries, may bias results. GBD does not distinguish acute from chronic pancreatitis, limiting subtype-specific analysis. The ecological design precludes causal inference, and unmeasured confounders (e.g., obesity, smoking, viral hepatitis) may influence outcomes. Alcohol attribution using the theoretical minimum risk exposure level may misrepresent heterogeneous drinking patterns, while decomposition analysis assumes independent additive effects despite potential interactions. Additionally, the lack of additional external databases restricted our ability to further validate the findings, underscoring the need for future research with broader data sources.Finally, projections reflect past trends and may not capture future policies or emerging risk factors.Nonetheless, the study highlights important global patterns and disparities in AAP.