Service and conservation corps programs offer young Americans a chance to address needs across the country’s built and natural environment while gaining valuable work experience and on-the-job training. In the process, corps members learn skills that are fundamental to operating and maintaining a variety of the country’s infrastructure and public works programs. Their activities span all kinds of communities, habitats, and other human-made and natural assets. As the U.S. grapples with aging infrastructure and struggles to hire, train, and retain a skilled workforce, there is a window of opportunity to strengthen the role that corps programs play in providing pathways into quality jobs and prosperous careers in infrastructure occupations, while at the same time meeting a critical need in the field for qualified workers.

This report outlines a set of corps-related occupations that service and conservation corps program leaders can use to align and improve career development for program participants, both during and after their term of service. This analysis uses Department of Labor data to identify occupations that correspond to the activities and tasks that corps members carry out, and then describes the workers in those occupations. With this information, service and conservation corps programs can better situate themselves in local labor markets to align with employer demand and prepare members for successful careers.

Collecting data on a consistent set of occupations over time—including ongoing analysis of employment, wage, training, and demographic trends—has the potential to equip service and conservation corps programs, other workforce development leaders, and employers with more actionable information about corps-related career opportunities. Based on that premise, the report finds that corps-related occupations:

Represent a significant share of employment in the U.S. There are 81 corps-related occupations, which employ nearly 13 million total workers—about 8% of all workers nationally.

Pay well, despite some notable differences by age. Median hourly wages for corps-related occupations are nearly $30 per hour, compared to $23.23 for all occupations. However, median wages are generally lower for occupations with high shares and/or numbers of workers 24 and under, with many ranging from about $17.50 per hour to the mid-$20s.

Have relatively low barriers to entry. About half of workers in corps-related occupations have a high school diploma or less, signaling the generally lower levels of formal education needed for entry into these positions.

Struggle with existing patterns of occupational segregation. Workers in corps-related occupations are disproportionately male, white, and aging—highlighting notable gaps to fill among a broader variety of prospective workers.

Service and conservation programs hold great potential to serve as talent pipelines for infrastructure employers—and in some cases, they already do. With enhanced capacities in career navigation and labor market analysis as well as stronger partnerships with area employers and other stakeholders, corps programs will be ideally positioned to launch their members into successful careers and help area employers find the workers they need.

Service and conservation corps programs offer young people the chance to address important community and environmental needs. As descendants of the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930s, they primarily focus on projects related to natural resources, infrastructure, and disaster mitigation. Corps members are generally ages 16 to 24, although sometimes are up to about age 30.

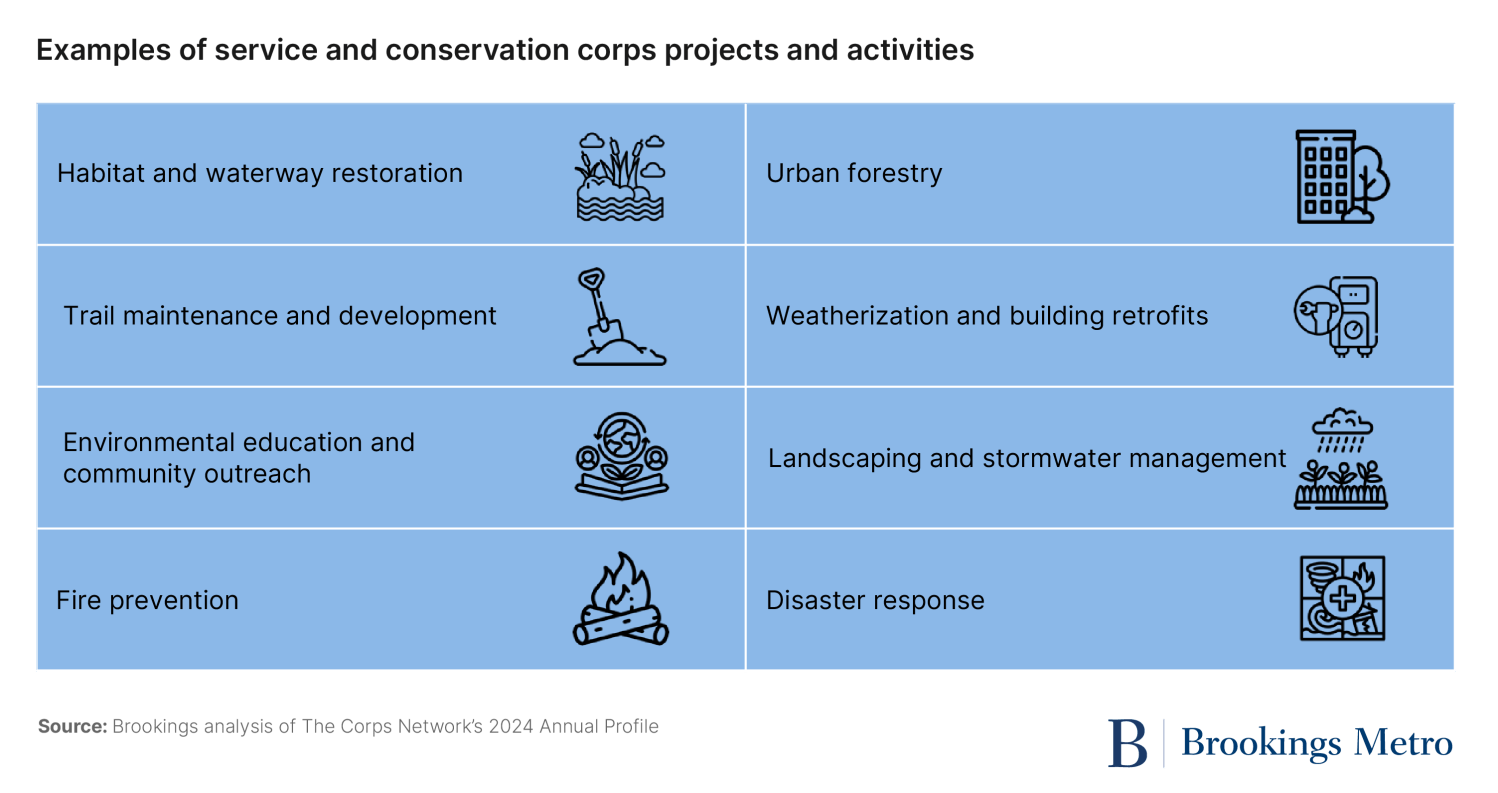

In 2024, more than 22,000 service and conservation corps members engaged in a wide variety of projects related to land and water management, public space improvement, disaster response, and energy efficiency—building and improving nearly 20,000 miles of trails, restoring 411,000 acres of habitat, responding to wildfires, prepping and placing thousands of sandbags, and planting 884,000 trees. A multitude of nonprofit organizations, universities, and local governments operate service and conservation corps programs, often with financial support from AmeriCorps, the federal national service agency.

Service and conservation corps programs are part of the broader national service field. Other national service programs may tutor K-12 students, assist with after-school programs, provide social services, or meet other community needs. In this report we use the terms “service and conservation corps” and “conservation corps” interchangeably, treating them as a subset of all national service programs.

Ideally, national service programs provide a “two-fer”: They offer valuable community services while also giving young people a structured and supportive pathway into the labor market and postsecondary education. And as described in a previous Brookings publication, “they offer a solid return on investment: An analysis of AmeriCorps-funded programs identified a cost-benefit ratio of 17.3 to 1. For every $1 in federal funds, the return to society, program members, and the government is $17.30.”

Figure 1

There is a significant overlap between the work that service and conservation programs carry out and the infrastructure sector more broadly. Both center their work on building, operating, and maintaining a variety of physical assets in the built and natural environment. The Corps Network, the national association of service and conservation corps, highlights the infrastructure sector as a key part of its work, noting that for over 80 years, corps programs have worked on “projects associated with trails and transportation, public lands access, water management, energy efficiency, habitat management, and disaster response and resiliency.”

Previous Brookings research found that the U.S. employs 16.6 million infrastructure workers across 95 occupations. Think of all the workers responsible for maintaining roads, streetscapes, and parks; managing water and energy systems; moving goods; upgrading buildings to be more energy efficient; and more. Many infrastructure positions are in the skilled trades, but there are also architects, engineers, water treatment and power plant operators, as well as positions more generally in management, finance, and customer service. Infrastructure workers generally have a wide range of transferable skills, including mechanical, technical, and scientific knowledge. Only a minority (13.6%) of them have earned a bachelor’s degree or higher, and most (86.8%) have some level of on-the-job training, whether through apprenticeships or shorter-term programs.

What is a corps?

According to The Corps Network, “Corps are local organizations that engage young adults (generally 16-30) and veterans (up to age 35) in service projects that address conservation and community needs. Through a term of service that could last a few months to a year, Corps participants—or ‘Corpsmembers’—gain work experience and develop in-demand skills. Corpsmembers are compensated with a stipend or living allowance and often receive an education award or scholarship upon completing their service. Additionally, Corps provide participants with educational programming, mentors, and access to career counseling.”

Source: The Corps Network

The potential of service and conservation corps programs to act as feeders into infrastructure jobs is particularly timely given that the infrastructure sector is struggling to find and retain workers. The infrastructure workforce skews older, with above-average shares of workers over age 45 and below-average shares under age 24. On average, an estimated 1.7 million infrastructure workers will need to be replaced each year over the next decade due to retirements and workers transitioning out of these jobs. Meanwhile, aging and vulnerable water infrastructure, inefficient and outmoded energy facilities, and outdated residential and commercial buildings all need upgrades and maintenance, requiring a continuous flow of talent. Moreover, floods, droughts, fires, and other acute and chronic impacts are adding to the urgency of these challenges.

Struggles to develop a skilled infrastructure workforce in the short and long term are widespread across the country—among employers, educational institutions, and other stakeholders. A lack of visibility and community outreach means that many prospective workers are unaware of careers in this space, whether training to become electricians, plumbers, or construction laborers. Major employers, such as energy and water utilities, can have rigid hiring and training requirements. Limited coordination among employers and other workforce and community partners—in addition to limited funding for work-based learning—also means that proactive planning and supportive services are often missing and can siphon off potential talent.

While infrastructure occupations are not identical to corps-related occupations (more on that below), there is enough of an overlap that infrastructure employers and corps programs would both benefit from stronger partnerships with each other. Employers need to develop stronger, more flexible talent pipelines for a greater number and variety of workers, and corps programs need to help develop career pathways for corps members after program completion.

The aim of this report is to support such partnerships by translating corps activities and projects into a specific set of occupations, and provide a framework for corps programs to develop stronger workforce development strategies. An occupational analysis is a foundational building block in workforce development. Absent an occupational framework, it is much harder for service and conservation corps programs and state service commissions to engage with employers and other regional workforce actors to connect corps members to careers.

Of course, this analysis is only the first step, but it can form the basis for further efforts to align corps programs more explicitly with employer demand. What employers and industries hire corps-related occupations? Are some occupations more in demand in a given area than others? How do corps curricula match up employer needs? Are there related sector initiatives or civic partnerships that corps programs should consider joining?

The next section of this report describes the methodology for this national analysis before highlighting several key findings around employment, wages, and demographics.

To identify and measure corps-related employment, we defined a consistent set of corps-related occupations nationally involved in constructing, maintaining, and overseeing the built and natural environment. Given the expansive set of industrial activities and built environment assets that these workers support, we did not limit the occupations to entry-level opportunities. Rather, our goal was to cast a wide net and consider the full range of occupations that these workers could fill in the short and long term. Doing so can better capture the wide range of career pathways potentially available to these workers over time.

Arriving at this list involved a multistep process—based on many prevailing occupational categories among federal statistical agencies, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics—to organize and filter the most relevant occupations:

As a starting point, we created a broad list building off previous Brookings research on infrastructure occupations that closely align with several corps-related activities.

We then filtered this initial list of infrastructure occupations by conducting an expansive literature review to evaluate and incorporate other previous occupational analyses that parallelled corps-related activities.

We circulated this targeted list for input among several strategic organizational partners, including The Corps Network and Urban Institute.

Lastly, we conducted a final expert review to ensure clarity and consistency across different occupations.

This final occupational list is based on the federal government’s Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system; we specifically examined detailed SOC occupations according to the 2018 SOC, the most current version available. This consistent list allowed us to analyze other public and proprietary data, including from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Lightcast. Beyond the individual occupations analyzed, we also developed a set of five “occupational families” to further aggregate and communicate trends across broader categories of employment: 1) buildings; 2) energy; 3) water; 4) land and forest management; and 5) hazardous materials, environmental remediation, and disaster response.

Additional details on this methodology are available in a downloadable appendix. An additional data file is also available that provides a more complete breakdown of all the corps occupations analyzed in this report.

Finding #1

There are 81 corps-related occupations that employ nearly 13 million workers, or about 8% of all workers nationally

Corps members carry out a wide range of projects that generally relate to constructing, maintaining, and overseeing the built and natural environment.

Collectively, 12.9 million workers are employed across 81 different occupations related to these activities. Only a small minority of these workers are corps members, so this is not a count of employment in corps programs. Rather, many of these occupations reflect a range of positions that may require additional education and experience, and involve progressively more responsibility and managerial oversight over time, including emergency management directors, architectural and engineering managers, and first-line supervisors of mechanics, installers, and repairers. These occupations, in turn, represent potential career possibilities for corps members as they gain more knowledge and experience while navigating different pathways.

The largest corps-related occupations overall, though, tend to be less specialized: general maintenance and repair workers (1.6 million) and construction laborers (1.1 million). Maintenance and repair workers keep machines, mechanical equipment, and building structures in good repair, while construction laborers perform a variety of physical activities at construction sites as well as in green infrastructure projects such as urban forestry. Other top occupations include landscaping and groundskeeping workers (962,000), first-line construction supervisors (811,000), and electricians (756,000). A complete list of occupations analyzed in this report is available for download.

Table 1

Corps-related occupations that employ the highest shares of younger workers include various “helper” occupations: people who assist electricians; pipelayers and plumbers; carpenters; and installation, maintenance, and repair workers. More than 30% of workers in these entry-level occupations are 24 years old or younger. However, since these occupations only represent between 25,000 to 100,000 workers total, these high shares do not necessarily translate into large numbers of young workers overall. Corps-related occupations with the greatest number of younger workers are also the largest occupations in general: construction laborers, landscaping workers, and maintenance and repair workers. This means that most younger workers are starting in larger, more generalized occupations that may or may not lead to more specialized career pathways.

Table 2

Corps-related occupations and green jobs

Despite the environmental focus of many corps programs, relatively few corps-related occupations identified in this analysis would be considered explicitly “green”—that is, geared toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions, adapting to climate impacts, or preserving/restoring natural resources.

This aligns with the growing consensus that meeting environmental or climate-related goals relies more on adding new tasks and skills to existing occupations than on creating new and distinct jobs.

For example, an analysis of the jobs generated by nearly 30 programs funded by the California Climate Investments initiative found that more than half were in the construction sector. Looking more granularly at particular types of corps-related activities, an analysis of occupations most relevant to green infrastructure and urban forestry projects found that only two of the 10 largest occupations relate directly to plants and soil. The other eight include the workers who build and maintain the elements that surround and contain green infrastructure and urban forestry facilities (construction laborers, carpenters, and plumbers), and workers who transport or move related materials (freight and material movers and truck or tractor operators).

Finding #2

Median hourly wages for corps-related occupations are nearly $30 per hour, compared to $23.23 for all occupations

Taken together, corps-related occupations pay median wages of $29.97 per hour, which is about 25% higher than the median hourly wage for all occupations ($23.23).

However, wages still vary considerably across individual corps-related occupations. At the low end, a cluster of entry-level positions and those not requiring specialized education and training pay a median wage between about $16 to $19 per hour; these include forest and conservation workers, a variety of construction “helpers,” and landscaping and groundskeeping workers. At the higher end, more senior positions such as construction managers and various engineers (environmental, electrical, and architectural) pay median wages between about $50 and $80 per hour.

Notably, corps-related occupations have a higher floor for workers at the bottom of the wage spectrum. At both the 10th and 25th percentiles ($19.55 and $23.93), hourly wages in corps-related occupations are 33% higher than in all occupations ($14 and $17.14). Higher levels of unionization and other prevailing industry norms, especially in the skilled trades, may partially explain such wage premiums, including for less experienced workers.

Figure 2

However, despite these competitive wages overall, many corps-related occupations with a greater share or number of younger workers tend to pay less. Various “helper” positions, construction laborers, landscaping workers, and maintenance and repair workers all pay about $18 to $23 per hour. Only a few occupations with high shares of young workers pay close to or above the median wage for all corps-related occupations ($29.97). These include electrical and electronics repairers ($32.06), electricians ($29.61), and plumbers ($29.59).

Table 3

Finding #3

About half of workers in corps occupations have a high school diploma or less, signaling the generally lower levels of formal education needed for these positions

In addition to the competitive wages and wide range of pathways available to workers in corps occupations, they also tend to need less formal education. Slightly more than half of these workers have a high school diploma or less, compared to 30% of workers across all occupations nationally. At the same time, 18.5% of workers in corps occupations have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 41.6% of all workers nationally. A roughly even share have associate degrees or some college experience.

Figure 3

Cement masons, construction laborers, and carpenters are among the largest corps occupations employing workers with a high school diploma or less; two-thirds of workers in these occupations demonstrate this level of educational attainment. Other sizable occupations, such as water treatment operators and electrical power line installers, also fall into this category, demonstrating the breadth of industrial activities and built environment sectors represented. However, several positions including landscape architects, civil engineers, and environmental scientists require more advanced levels of formal education; in these cases, more than three-quarters of workers have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Similar to the broader infrastructure workforce, workers in corps occupations often gain more knowledge and experience on the job. Worker surveys in many related positions, especially in the skilled trades, emphasize science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, as well as familiarity with public safety and security, law and government, and a mix of other hard and soft skills. Electricians and plumbers, for instance, demonstrate a variety of skills to carry out their work, such as developing plans, making needed repairs, and interacting with residents and businesses. Work-based learning opportunities, including internships and apprenticeships, are common across these positions, where employers drive many learning and growth opportunities.

Finding #4

Workers in corps-related occupations are disproportionately male, white, and aging—highlighting notable gaps to fill among a broader variety of prospective workers

Attracting—and retaining—different types of workers demographically remains a challenge for many corps occupations.

Perhaps the most striking disparities are among male and female workers. Nearly 92% of workers in corps occupations are male—significantly higher than the 50% share of workers in all occupations nationally. From mobile heavy equipment mechanics and HVAC technicians to pipelayers and brick masons, nearly every corps occupation is male-dominated, in line with long-standing historical trends in construction and skilled trades. Only one of the 81 total corps occupations had above-average shares of women: natural sciences managers (54.4%). However, this gender imbalance was less pronounced in The Corps Network programs (38% female), perhaps revealing challenges around growth and retention for women as they progress beyond these programs.

Figure 4

Looking at specific occupations, the differences in gender align with differences in educational attainment. Occupations with high shares of women are more likely to be professional positions in which a college degree is common or required. Examples include natural sciences managers (54% female, 91% with a BA or higher) and environmental scientists (41% female, 100% BA or higher). By contrast, there are 25 occupations in which women make up less than 5% of the workforce, and among them, the occupation with the highest share of workers with a BA is 16%. Examples include plumbers (98% male, 6% with a BA) and HVAC mechanics and installers (98% male, 7% with a BA).

Figure 5

Racial diversity is also frequently lacking in many corps occupations. Nearly two-thirds (65.5%) of these workers are white, compared to 60.3% in all occupations nationally. Sixty-three of the 81 corps occupations employ above-average shares of white workers, spanning a variety of activities from meter readers and septic tank servicers to construction managers and landscape architects. Meanwhile, 7.8% of workers in corps occupations are Black (versus 12.9% in all occupations) and 3.2% are Asian American (versus 6.6% in all occupations). The only exception is Latino or Hispanic workers, who account for 20.7% of corps employment—slightly higher than the all-occupation average of 17.1%. Their prevalence in many construction-related positions weighs heavily here. According to The Corps Network’s FY 2024 Annual Report, corps members show greater racial diversity: 56% are white, 15% are Black, and 12% are “other.”

Lastly, many workers in corps occupations are aging, part of the larger “silver tsunami” hitting many skilled trades positions and demonstrating a need to grow younger talent. For instance, 39.4% of these workers are 45 to 64 years old, while 36.2% of all workers nationally fall into this age bracket. At the same time, only 9.8% of workers in corps occupations are 24 years old or younger, compared to 13.3% of all workers nationally. These shares can be even more extreme in certain positions, such as water treatment operators, electrical engineers, and power distributors and dispatchers, all of which have 43% or more of their workers between 45 and 64 years in age and 6% or fewer of their workers under 24 years in age. The extensive on-the-job training and credentialing requirements needed for these positions likely explain some of these gaps, but employers and other leaders continue struggling to expand talent pipelines among a broader range of age groups.

Service and conservation corps programs can feed into a variety of occupations that pay competitive wages, require lower levels of formal educational attainment, and offer meaningful career pathways for corps members. The field is ripe to incorporate stronger workforce development components and work more intentionally with employers and other workforce development actors. The following section provides some ideas about how to do so.

Segmenting corps-related occupations into five ‘occupational families’ helps develop and codify more targeted workforce development strategies

The 81 occupations identified in this analysis represent an unwieldy number for workforce development program development or strategizing. Most workforce development organizations focus on a smaller number of occupations or create subgroups of occupations that align with each other; they may belong to the same industry, have similar or overlapping skill sets, or represent different nodes along a career pathway. In that way, these organizations can better target their planning and partnerships with employers and other groups.

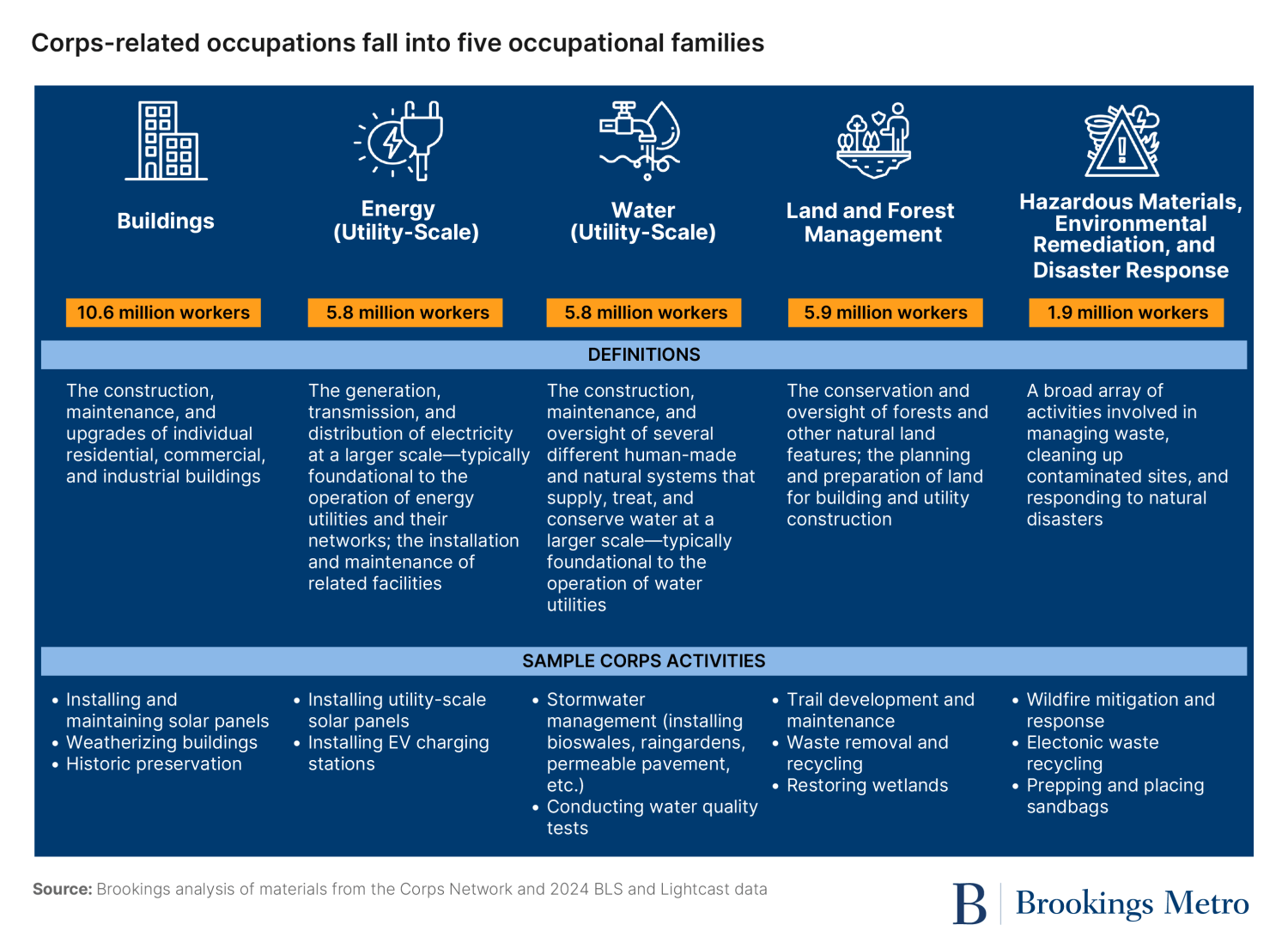

To support corps programs in developing a more focused workforce development approach (and recognizing that corps programs already specialize in particular types of work), this report defines five “occupational families.” The designations are based on information from The Corps Network about the activities, projects, and priorities of service and conservation corps programs. Occupational families consist of the following categories: 1) buildings; 2) energy; 3) water; 4) land and forest management; and 5) hazardous materials, environment remediation, and disaster response.

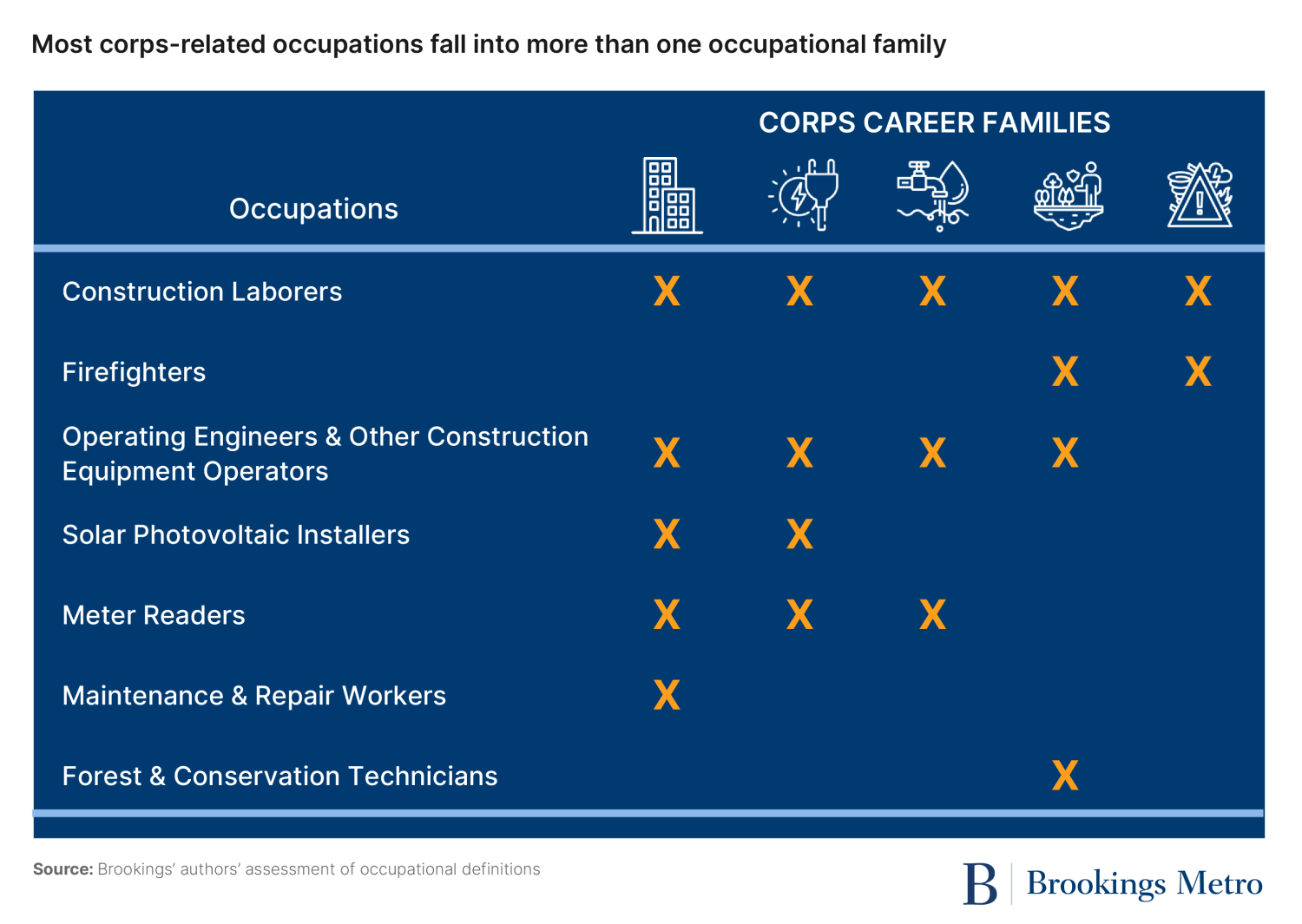

We placed each occupation into one or more families. A construction laborer, for example, can help weatherize homes to improve energy efficiency (buildings), contribute to urban forestry projects (land and forestry management), and prepare construction and installation sites (any of the five categories). A meter reader could work in the buildings, energy, or water families. The occupational families succinctly capture the range of work that corps members do across the built and natural environment—and the reality that these occupations are often defined by multiple branching career pathways.

Figure 6

The buildings family has the largest employment (10.6 million workers), and includes electricians, plumbers, civil engineers, construction laborers, and electrical power line installers. Electricians and civil engineers also appear in the energy, water, and forest and land management families, while power line installers appear in energy as well as buildings. In comparison, the hazardous materials, environmental remediation, and disaster response family depends on a relatively smaller and specialized set of occupations (such as refuse and recyclable material collectors and hazardous materials removal workers) and has the lowest employment (1.9 million workers).

Figure 7

The current policy landscape is fluid

It is admittedly an uncertain time for service and conservation programs given recent actions by the Trump administration. This spring, AmeriCorps (the federal agency that funds national service programs, including many service and conservation programs) laid off most of its staff and terminated nearly $400 million in active grants. In response, a number of states filed suit and a preliminary injunction directed AmeriCorps funding to be restored in the states that are parties to the lawsuit. Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s proposed FY 2026 budget would eliminate AmeriCorps.

A newly launched Department of Interior initiative, the Patriot Program, bears a resemblance to corps programs, although it is not described as such. A three-year, $250 million initiative, the Patriot Program will engage youth and young adults in projects to “restore and revitalize public lands” through projects such as historic preservation, masonry repairs, wildland fuel reduction, and trail maintenance to improve access to iconic sites. It will “provide hands-on training in skilled trades and foster pathways to sustainable career [paths]” and require a 50% match in private funding for every federal dollar, but few other details are available.

At the state and local level, governments have shown a surge in support for service and conservation corps in recent years, expanding beyond federal AmeriCorps-funded programs. In Maryland, Governor Wes Moore created the Service Year Option for high school graduates and GED recipients, and revamped an existing program, Maryland Corps, to serve adults of all ages.

Similarly, in California, Governor Gavin Newsom developed the College Corps, Climate Action Corps, and Youth Service Corps. An incomplete list of other states expanding their service programs includes Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Vermont. Relatedly, there is also momentum for national service to connect more intentionally to post-service employment and careers. Some of these initiatives have used or leveraged AmeriCorps funding, while others rely primarily on state funding.

At the same time, state and local leaders remain firmly in the driver’s seat when it comes to infrastructure ownership and operation, including short- and long-term planning, funding and financing, and workforce development. As the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act sunsets in 2026 (and questions continue to swirl around the Inflation Reduction Act’s climate provisions), the reality is that transportation departments, water utilities, and other state and local entities are continuing to oversee the vast majority of the country’s infrastructure spending each year (79% according to recent Congressional Budget Office estimates). This means that they will need to continue hiring, training, and retaining a skilled workforce, and reaching younger workers will need to be a big part of that effort.

The main takeaway for corps programs and other policymakers and practitioners is this: Even amid federal uncertainty, many state and local leaders are increasingly emphasizing service and conservations corps programming and looking to accelerate a variety of infrastructure projects in need of talent.

Service and conservation corps are well positioned to serve as sources of talent to infrastructure-related employers. They are deeply knowledgeable about the skills and competencies required for the projects they carry out, and they can map this information to occupational demand in the region. Moreover, as a previous Brookings publication described, their program model of work-based learning “provides corps members the chance to learn technical, applied, and interpersonal skills in ways that are difficult to achieve in the classroom alone.” This approach gives corps members the chance to test out a field of practice and gain exposure to different types of jobs before fully committing to any specific occupation or employer. Thus, job candidates referred from service and conservation corps programs are likely to not only be prepared, but also familiar with the nature of the work, which will help with retention as they are less likely to decide the job is not a good fit for them.

That being said, most service and conservation programs will need to develop new capacities and partnerships if they are to more intentionally support members’ career development during and after their term of service. Making these changes is not necessarily easy or quick, given all of the other responsibilities and constraints that conservation corps face. However, developing a stronger workforce development focus may be a strategic choice in a changing policy landscape if it helps identify new champions and funding sources.

Looking internally, programs can ask themselves:

Does the work that corps members carry out align with any of the occupations and occupational families profiled here? How do the skills corps members learn during their service relate to the typical skills needed in a related entry-level job? Does the program offer industry-recognized certifications?

What kinds of career exploration and preparation does a given program offer members? Is it incorporated throughout the program or as an isolated component toward the end?

Does this program have relationships with area employers, chambers of commerce, industry associations, workforce development agencies, and other related organizations? (These relationships can help programs understand and track local labor market needs and cultivate job opportunities for corps members.)

Do staffing patterns and job descriptions in the program reflect a focus on career exploration, partnerships with external organizations, and job placement?

Then, these programs need to look outward and take a closer look at the state and local education and workforce development ecosystem, as well as other related state and local infrastructure programs (e.g., transportation, energy, and water agencies). While they are probably at least somewhat familiar with these entities, they should now ask more focused questions, with an eye toward identifying partnerships they can join, support, or form.

Do area community colleges provide relevant training or degree programs? Do other community-based organizations or nonprofits offer similar training? Would there be any benefits in collaborating on employer outreach and labor market analysis?

Are there related apprenticeship programs the program could feed into?

What are the priorities and services provided by state and local workforce development boards and labor/employment agencies?

Has the state service commission focused on any specific sectors or occupations, and have they identified workforce development as a priority?

Are there state and local chambers of commerce or industry associations that are involved in workforce development?

Is there an existing sector-based workforce development initiative aligned with corps’ focus occupations? (Sector-based initiatives focus on meeting the workforce needs of particular industries and occupations—typically those with strong labor demand and in which workers without college degrees can earn living wages.)

Workforce development is a team sport, and partnerships or collaborative efforts are essential. That’s why understanding the local ecosystem is so important. No one organization has the capacity to carry out all the necessary functions:

Recruiting from diverse and underserved populations

Providing any necessary supportive or wraparound services

Using quantitative and qualitative data to understand regional labor markets and employer needs, inform curricula, and cultivate job placements

Providing education and training, which can include employment readiness and basic skills, on-the-job training, apprenticeships, preparing people to earn industry-recognized credentials, and academic offerings leading to postsecondary degrees and certificates

Providing career navigation, job placement, and retention services to corps members

Of the above functions, service and conservation corps programs are probably the least developed in labor market analysis. A key question for programs is determining the right balance between developing internal capacity and participating in partnerships or coalitions that offer those elements.

Regardless, it is hard to imagine a future in which corps programs do not provide important benefits to communities, employers, and corps members. That benefit can only increase if corps programs strengthen their role as sources of talent to area employers and better prepare their members for successful careers.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).