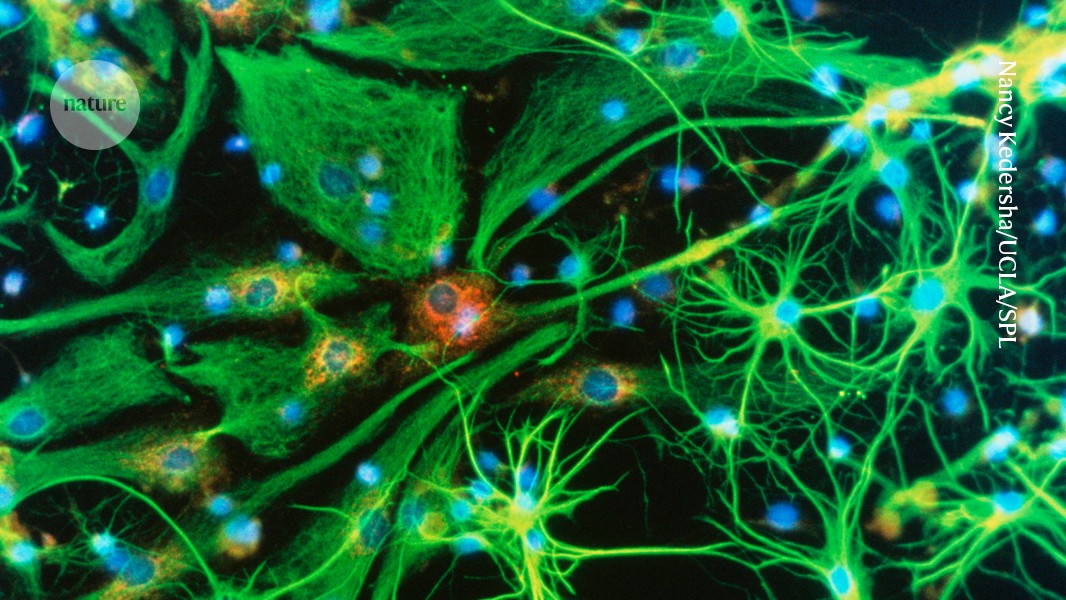

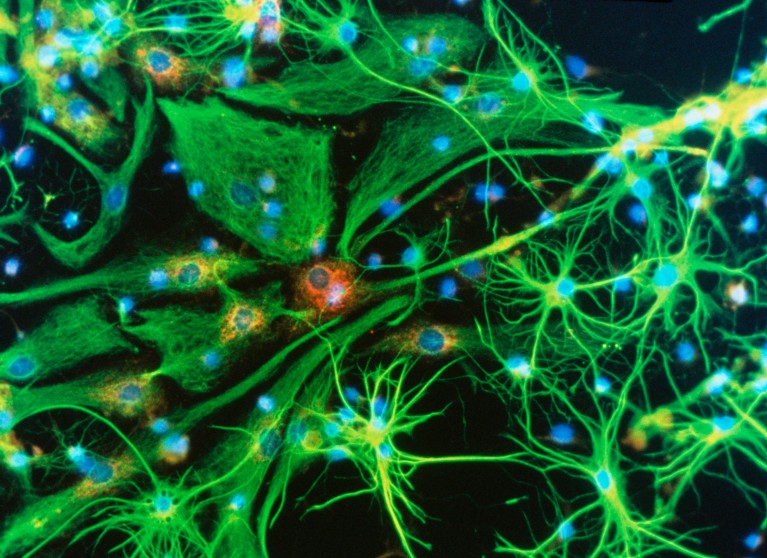

Brain cells (artificially coloured) can be infected by a virus carrying the apperatus to correct disease-causing mutations. Credit: Nancy Kedersha/UCLA/Science Photo Library

Scientists are closing in on the ability to apply genome editing to a formidable new target: the human brain.

In the past two years, a spate of technological advances and promising results in mice have been laying the groundwork for treating devastating brain disorders using techniques derived from CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing. Researchers hope that human trials are just a few years away.

“The data have never looked so good,” says Monica Coenraads, founder and chief executive of the Rett Syndrome Research Trust in Trumbull, Connecticut. “This is less and less science fiction, and closer to reality.”

Daunting challenge

Researchers have already developed gene-editing therapies to treat diseases of the blood, liver and eyes. In May, researchers reported1 a stunning success using a bespoke gene-editing therapy to treat a baby boy named KJ with a deadly liver disease.

But the brain poses special challenges. The molecular components needed to treat KJ were inserted into fatty particles that naturally accumulate in the liver. Researchers are searching for similar particles that can selectively target the brain, which is surrounded by a defensive barrier that can prevent many substances from entering.

World’s first personalized CRISPR therapy given to baby with genetic disease

Although KJ’s story was exciting, it was also frustrating for those whose family members have neurological diseases, says Coenraads, whose organization focuses on Rett syndrome, a rare disorder that affects brain development. “The question that I hear from our families is, ‘It was done so quickly for him. What’s taking us so long?’” she says.

That pool of concerned families is growing as physicians and families increasingly turn to genome sequencing to find the causes of once-mysterious brain disorders, says Cathleen Lutz, a geneticist at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. “People are starting to now find out that their child’s seizures, for example, are related to particular genetic mutations,” she says.

Snip and stitch

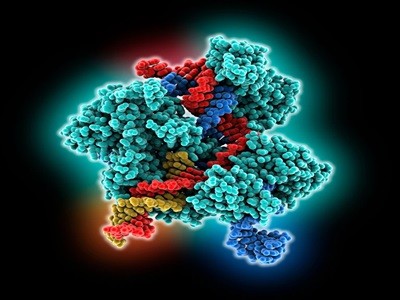

Studies in mice suggest that gene-editing technology, which can rewrite small snippets of a cell’s genome, is ready to correct some of these mutations. In July, researchers reported2 that they had repaired mutations that, in humans, cause a disease called alternating hemiplegia of childhood (AHC). The condition, which typically starts causing symptoms before a child reaches 18 months old, causes seizures, learning disabilities and episodes of partial paralysis. “It’s a horrible disease,” says David Liu, a chemical biologist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Liu and his colleagues deployed a gene-editing offshoot of CRISPR called prime editing in mice with a mutation that causes AHC. The technique corrected the mutation in about half of the brain’s cortex, a region that controls learning and memory. The mice also showed improvements in a variety of measures: their seizure-like episodes became less severe, cognition and motor control improved and lifespans lengthened. “The mouse results were dramatic,” says Liu. “We were amazed.”

World first: ultra-powerful CRISPR treatment trialled in a person

Liu’s laboratory is also working in mice to correct mutations that cause two other neurological disorders: Huntington’s disease and Friedreich’s ataxia in people3. And at the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China, neuroscientist Zilong Qiu and his colleagues have used base editing to correct a mutation in a gene called MEF2C4. In human children, this mutation can cause epilepsy, intellectual disability and limited verbal ability.

In male mice, the same mutations alter how the rodents behave around fellow mice. Correction of the Mef2c mutation by base editing, an ultra-precise version of CRISPR genome editing that corrects single DNA letters, restored normal social behaviour and improved the connections between nerve cells.

Qiu and Liu are also independently working on gene-editing therapies to treat Rett syndrome, which is most often caused by mutations in a gene called MECP2. A gene-editing approach is particularly important for this condition, says Coenraads: simply adding an extra, normal copy of the entire MECP2 gene, as conventional gene therapy would, could cause cells to produce too much of the corresponding protein. High levels of that protein can be toxic.

But gene editing would merely correct the natural copy of the gene, and is less likely to cause excess production of MECP2, says Qiu.

Financial woes

It is a long road from results in mice to human clinical trials. Qiu hopes that his team will be ready in about five years to try a base-editing therapy in people with Rett’s syndrome. And Liu’s team hopes that, within the next few years, they can tackle the remaining experiments needed to launch studies in people with AHC.

CRISPR genome-editing grows up: advanced therapies head for the clinic

Because fatty particles, such as those used in KJ’s treatment, are not yet an option, both teams anticipate that clinical trials would use a virus called adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) to shuttle gene-editing components into the brain. This virus can infect brain cells and is somewhat able to cross the blood–brain barrier.

AAV9 comes with risks, however, because high doses of the virus can ignite deadly immune responses. Researchers are racing to develop improved viruses that can be used at lower doses5. And Coenraad’s organization is funding efforts to develop virus-free methods that can deliver molecules to brain cells.

In the end, the biggest barrier might not be technological. In the United States, the biotechnology industry is mired in a lengthy financial slump. Some investors have pulled away from gene therapies and gene-editing approaches, which are expensive and difficult to produce. “The money is drying up,” says Coenraads, who says that she tries to stay optimistic.

“Things tend to go in a pendulum,” she says. “For now, I think we keep our head down and generate good data.”