This study identified significant disparities in the burden of IBD across five East Asian countries, with a distinct correlation between these variations and each country’s socioeconomic development level (SDI) level. Through comparative analyses of countries with high, medium and low SDIs, we constructed a multidimensional explanatory framework.

Firstly, in terms of the healthcare system, countries with a high SDI (such as Japan and Korea) have achieved effective disease control thanks to their well-developed healthcare infrastructures [10,11,12,13]. Notably, Korea has achieved a significant improvement in early-stage colorectal cancer detection rates through the integration of colonoscopy into its national cancer screening program [14, 15]. By contrast, China, a medium SDI country, has achieved a significant ASMR (Age-Standardized Mortality Rate) decline of 47.2% by investing in healthcare resources and increasing its health expenditure to 7% of GDP. However, it is facing a surge in morbidity driven by urbanisation. Notably, since the introduction of biologics (e.g., infliximab) into China’s healthcare system in 2006 and their subsequent inclusion in national insurance coverage [16], The combined effects of improved medical capacity, earlier diagnosis, and advanced therapeutics have contributed to a 47.2% decline in ASMR and reduced DALY rates per capita [17]. However, rapid urbanization continues to drive rising morbidity, creating a dual challenge of expanding treatment access while managing a growing patient pool. Conversely, Mongolia, a low SDI country, exhibited an unusual pattern of ‘early onset and high disability’ due to a shortage of primary care resources [18, 19].

Secondly, in terms of lifestyle, The westernisation of dietary habits was found to have a significant dose-response relationship with an increase in morbidity. The 4.6-fold increase in fast food consumption in Korea and the 3-fold increase in animal protein intake in China were consistent with the surge in IBD incidence [20,21,22]. In contrast, North Korea, which maintains a traditional diet, had a low incidence (AAPC = 0.60%). According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database, North Korea is one of the few countries showing a declining trend in both the incidence and prevalence of IBD. However, this statistical trend may not accurately reflect the true epidemiological situation of IBD in the country. Since The 1990s, North Korea’s healthcare system has suffered severe setbacks due to persistent natural disasters, economic difficulties, and crises in food and energy supply. The country’s public health infrastructure remains weak, and essential diagnostic tools for IBD—such as colonoscopy, imaging, and pathological evaluation—are critically lacking. As a result, a significant number of potential patients go undiagnosed and untreated [23, 24]. These findings provide epidemiological evidence for the ‘diet-microbiota-immunomodulation’ hypothesis.

Thirdly, in the healthcare coverage dimension, differences in diagnostic capacity and treatment accessibility significantly affect disease burden. First, taking Africa as an example, many countries face significant challenges in addressing both infectious and non-communicable diseases. For instance, research on hypertension management in Tanzania reveals that inherent limitations in the healthcare system—including insufficient knowledge among medical staff, limited system capacity, difficulties in accessing medications, and low patient awareness—result in poor screening and management outcomes [25]. Similarly, in Sierra Leone, the high incidence and mortality rates of cryptococcal disease among HIV patients highlight how the lack of effective screening and treatment strategies severely undermines disease control [26].These differences directly contribute to significant variations in disease detection rates and prognosis.

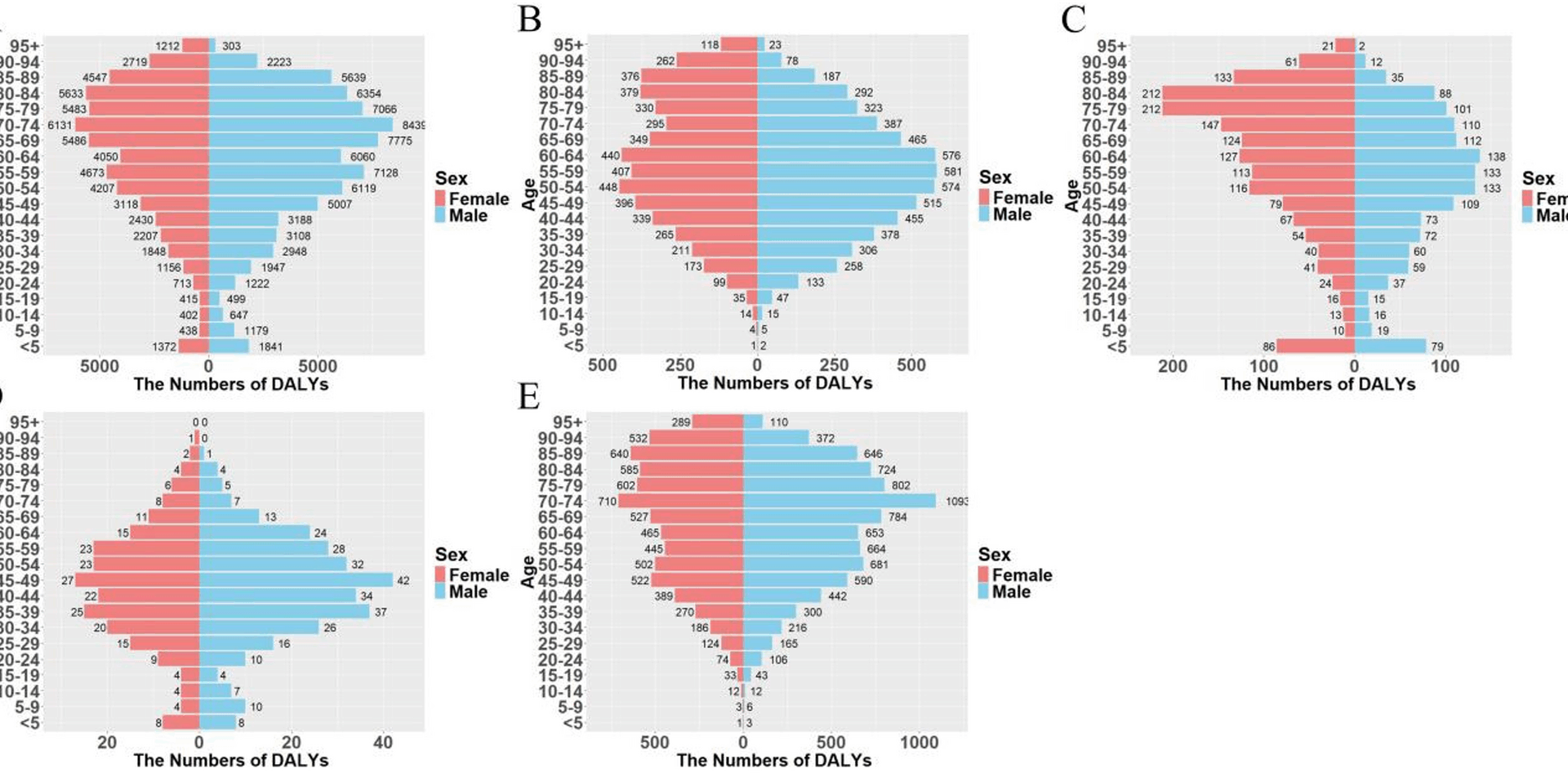

This study reveals divergent aging-related IBD patterns influenced by socioeconomic development. In China (medium SDI), the observed epidemiological shift stems from multiple factors. First, accelerated population aging has significantly expanded the elderly demographic base, becoming a major contributor to IBD burden growth [27]. Second, prolonged exposure to risk factors—including high-fat/salt diets, antibiotic overuse, and urban environmental pollution—has degraded gut microbiota and immune function in this cohort, elevating disease susceptibility. Notably, China’s improved health management for seniors has concurrently enhanced case identification rates. These dynamics mirror though distinct from high-SDI contexts: While Korea demonstrates 97% treatment coverage under its social health insurance system [11]—slashing mortality through timely biologics and surveillance—the expanding elderly cohort (70 + years) has paradoxically increased absolute DALYs. This trend reflects both longer patient survival and higher late-onset IBD incidence in aging populations, suggesting that even optimal healthcare cannot fully offset demographic pressures. Of particular interest, The APC model indicates a high-risk profile among younger cohorts. The RR reached 3.36 for The 2017 birth cohort in Mongolia and 3.92 for the post-1990s cohort in China [28]. This incremental intergenerational risk is closely associated with early-life antibiotic misuse (a 150% increase in Mongolia) and drastic dietary changes (a 400% increase in fast-food consumption among Chinese adolescents), suggesting an accelerated and earlier-onset disease burden.

Based on these findings, we propose the following tiered strategy for prevention and control: improving The elderly care system in high SDI countries, strengthening preventive interventions for adolescents in medium SDI countries, and prioritising the establishment of grassroots screening networks in low SDI countries. First, in high-SDI countries, the growing elderly population presents new challenges to healthcare systems. Research indicates that population aging will significantly increase the burden of dementia, with high-SDI countries facing a 169% higher dementia burden compared to low-SDI nations [29]. Consequently, strengthening elderly care systems—particularly in dementia prevention and management—has become a priority for high-SDI countries. Studies demonstrate that early investment in effective preventive measures can reduce the incidence and complications of chronic diseases, thereby conserving healthcare and social service resources [30].Furthermore, preventive interventions targeting adolescents are crucial in middle-SDI countries. Studies reveal a growing prevalence of mental health issues among adolescents, particularly in middle-SDI nations [31]. Strengthening preventive measures such as mental health education and early intervention can effectively reduce the incidence of these disorders. Additionally, multidisciplinary interventions for adolescents have demonstrated positive effects in promoting healthier behaviors [32].Finally, establishing primary-level screening networks should be prioritized in low-SDI countries. Research indicates these nations bear a disproportionately high burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) while lacking adequate health system capacity for effective response [33]. Implementing community-based screening networks enables early disease detection and management, thereby reducing the overall disease burden. This strategy not only improves health outcomes but also contributes to economic development by curtailing healthcare expenditures [34].

Although this study systematically analyzed trends in The burden of IBD across five East Asian countries from 1990 to 2021, several limitations should be noted. First, the data were entirely sourced from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database. While GBD ensures global comparability, the lack of primary clinical registry data—particularly from North Korea and Mongolia, where epidemiological surveillance systems are underdeveloped—may lead to estimation errors and potential underestimation of disease burden. Second, variations in diagnostic criteria, reporting systems, and colonoscopy availability across countries may introduce systematic bias in cross-national comparisons. Third, the study did not incorporate key etiological factors (e.g., dietary changes, antibiotic use, urbanization) into predictive models, limiting causal interpretation of rising incidence rates. Fourth, analyzing IBD as an aggregate without distinguishing between Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) may reduce the precision of disease-specific prevention strategies. Finally, while improved therapies were acknowledged as a potential factor in burden reduction, quantifiable policy metrics (e.g., health insurance coverage, biologics adoption, screening policies) were not included, restricting concrete assessment of public health intervention effectiveness. These limitations highlight the need for future research incorporating national registries, standardized diagnostic validation, etiological analyses, and policy impact evaluations.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study’s innovative value lies in its construction of the first three-dimensional ‘status-mechanism-intervention’ analysis framework for IBD in East Asia. Building upon our findings while addressing the current constraints, this framework provides a scientific basis for the development of regional differentiation strategies. Moving forward, we must improve data quality through multi-centre registries and explore the environment-gene interaction mechanism to improve the accuracy of prevention and control measures. Taken together, these findings not only deepen our understanding of the epidemiological transition of IBD but also provide an important reference for the prevention and control of other chronic diseases.