POKC is a particular type of OKC. Investigating the origin of POKC is critical, and its origin may potentially be deduced based on that of OKC. The most common theory suggests that OKCs arise from remnants of the dental lamina, which maintain their odontogenic potential and proliferate over time [3]. However, another hypothesis suggests that OKCs may originate from the basal cells of the oral mucosal epithelium, which is the origin of the dental lamina [4, 5]. These basal cells retain their ability for odontogenic differentiation and cause different lesions, such as peripheral ameloblastomas or OKCs, located within gingival tissues, especially in patients with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome [6,7,8]. Gorlin–Goltz syndrome or Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) is an autosomal dominant inherited condition comprising the principle triad of basal cell carcinomas, multiple jaw keratocytes, and skeletal anomaly [9]. Researchers have discovered that patents with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome have mutations in the PTCH1 gene, and the immunohistochemical results suggested that the OKC and POKC lesions were caused by a genetic alteration in the patients’ PTCH1-GLI gene [10]. The correlation between Gorlin–Goltz syndrome and POKC still needs to be further verified.

The clinical manifestations of POKC are nonspecific, often including soft tissue swelling. Patients may also exhibit restricted mouth opening if the mass involves adjacent structures such as the masticatory muscle [11]. The commonly used imaging examination methods include panoramic radiography, ultrasound, CT and MRI [12]. Strategies for treating and managing POKC have not been adequately documented thus far. In most studies on POKCs, the treatment modalities mainly include enucleation, curettage, and excision. In some cases, ostectomy, electrocautery, chlorhexidine rinses, and reconstruction with flaps were used [13]. Currently, the most common treatment methods for POKC are the same as those for OKC, and the main approach is curettage. This intraoral approach causes minimal trauma and allows complete lesion resection in one session [8, 14]. The recurrence rate of OKC treated by curettage alone is approximately 17% − 54.5%, mostly because of residual lesion [15, 16]. Marsupialization or decompression has been used as a more conservative form of treatment for a large OKC to minimize the cyst size and to limit the extent of surgery [8, 17]. Tucker et al. [18] reported a large mandibular OKC in a 15-year-old boy treated by decompression and secondary enucleation. Marker et al. [19] reported long-term results after decompression for 23 OKCs, and they concluded that these cysts could be treated successfully by decompression and subsequent enucleation.

A systematic literature review was performed by searching the Elsevier Journals, Web of Science, Wiley Online Library and PubMed databases for available case report articles on patients with POKC using the search terms “Peripheral odontogenic keratocyst”, “Keratocystic odontogenic tumor” and “Review” up to 2025. In addition, we performed the inspection of references of the identified articles, including case reports of peripheral tissue-originating cases that were clearly diagnosed as OKC and excluding articles not available in English, cases with unclear diagnoses or severe data deficiencies. We identified a total of 37 English articles, which collectively reported 51 cases, as detailed in Table 1. The review included 26 males and 22 females. The average age of the patients was 54 years (ranging from 14 to 83 years). Among them, 29 POKCs (56.9%) developed in the gingiva, and 14 (27.5%) involved the buccal mucosa. There were also 8 isolated cases where the onset location was in the temporal muscle (3), temporomandibular joint (1), masseter muscle (1), masticatory space (1), retromolar pad (1), and oropharynx (1). Among the reported cases of gingival POKC, 11 cases (37.9%) involved the mandibular gingiva, 14 cases (48.3%) involved the maxillary gingiva, 1 case involved both the maxillary and mandibular gingiva, and 3 cases had unknown involvement. Notably, 2 patients had POKCs in the gingiva as well as nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS). The chief complaint of 28 patients was swelling. Of these patients, 9 had pain, 4 had restricted mouth opening, 1 experienced discomfort while chewing, and 1 developed numbness. Two patients reported that they could feel the mass enlarging, and 1 of them felt that the mass affected appearance. One patient reported that a bite caused the mass.

Table 1 Clinical characteristic of reported cases of peripheral odontogenic keratocyst (POKC)

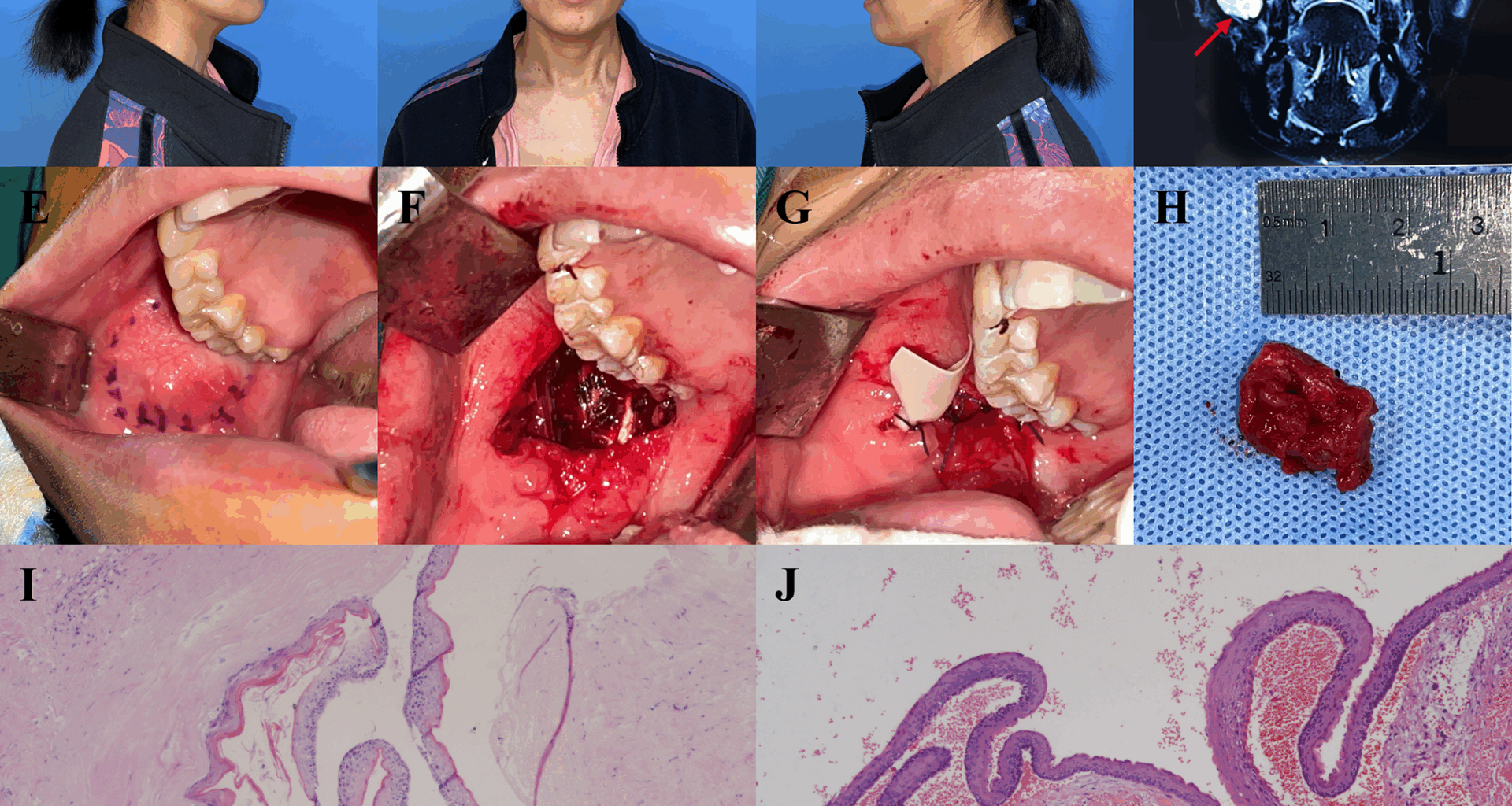

By reviewing the literature, we found that enucleation, curettage, removal, resection, or decompression only removed the tumor, while excision typically involved removal part of the surrounding tissue. Excision in the case of adhesion is more invasive than others. In previous reports, 14 patients were treated with tumor removal alone [22, 26, 27, 31, 33, 34, 39, 43, 45, 53, 54], and 5 of them experienced recurrence after surgery [27, 31, 34, 45, 53]. 15 patients underwent excision and osteotomy directly with no recurrence after the operation [11, 28, 37, 38, 40, 43, 44, 46,47,48,49, 51, 52]. Furthermore, following the initial surgery, 2 patients experienced recurrence and no further recurrence was observed after subsequent excision procedures [27, 50]. Similarly, the two cases we presented here also recurred after the primary surgery, and there was no recurrence after subsequent excision.

Overall, in 34 patients whose follow-up records were available, 7 patients (20.6%) experienced recurrence [24, 27, 31, 34, 49, 50, 53]. In addition, 3 patients had previously developed mandibular OKCs [23, 45, 54]. The recurrence rate of POKCs in the gingiva was 31.25% (5 of 16) and that in the buccal mucosa was 9.1% (1 of 11). However, among all the patients followed up, only 11 were followed up for more than 3 years [11, 23, 24, 26, 30, 39, 40, 44, 49, 51], in which 2 patients with buccal POKCs and 6 patients with gingiva POKCs. Therefore, we believe that the recurrence rate of POKCs may be underestimated and that rate may be higher if patients can be followed up to more than 3 years. Our study is the second report on the recurrence of POKCs in the buccal mucosa, with a follow-up period of more than 50 months from the initial surgery. In Takuma Watanabe’s report, the cyst was not completely resected in the first two operations due to the large scope of the lesion and punctured cyst wall. At the third operation, the lesion was completely removed with the surrounding mucosal tissue and proximal bone. No recurrence was observed during the later follow-up. Based on observations from our two patients, we propose that two primary factors may compromise the therapeutic efficacy in POKCs. First, unlike intraosseous OKCs, POKCs are not easily decompressed due to insufficient soft tissue support, which compromises plug stabilization and often leads to unsatisfactory outcomes. Second, the frequent involvement of critical anatomical structures—such as the oropharynx, maxilla, and adjacent muscles—complicates complete excision. Simple enucleation in such cases increases the risk of leaving residual lesion, thereby elevating recurrence potential. Thus, complete excision is effective for POKC. Additionally, the use of a surgical microscope is also encouraged to improve separation accuracy and reduce damage to adjacent tissue.

Our report is by far the most comprehensive English review on POKC. Due to the rarity of POKC, all the reports were sporadic retrospective cases with limitations. Given the heterogeneity mentioned above, we believe that the current data is insufficient for a Meta-analysis. Although we adhered to structured search and reporting principles, the aim is to draw attention to the existing treatment strategies by presenting two rare cases, rather than providing evidence-based recommendations. We encourage the establishment of an international POKC registration system so that a comprehensive and systematic review can be conducted to assist doctors in exploring more effective treatment methods.