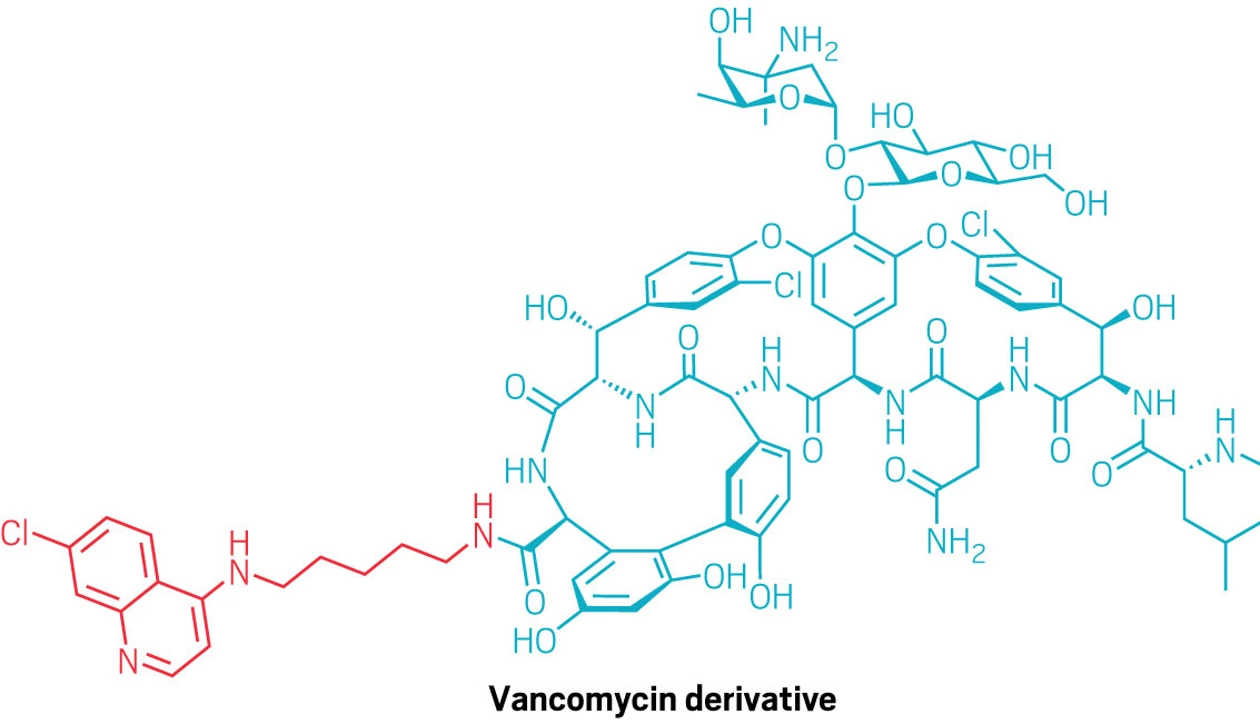

Vancomycin is a common antibiotic used to treat gram-positive bacterial infections. It targets a key building block of the bacterial cell wall called Lipid II, but it can’t reach this lipid in gram-negative pathogens because their outer membranes block such large molecules. Now, chemists at the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences have found that attaching a small quinoline group to vancomycin lets it slip inside the bacteria and reach its target (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5c14268).

“It’s genuinely surprising that the add-on gives vancomycin any ability at all to hit gram negatives,” says Kim Lewis, an antibiotic researcher at Northeastern University who was not involved in the study.

Previously, chemists had tried attaching cationic groups, transport peptides, or hydrophobic anchors to vancomycin—methods that increase the permeability of the outer membrane but are only modestly effective at pushing the drug inside. Unlike those approaches, the quinoline tweak appears to work without forcing open the membrane; it’s a gentler route that may reduce toxicity and make resistance harder to evolve.

While the team originally added the quinoline to boost vancomycin’s activity against resistant gram-positive bacteria, several of the modified molecules unexpectedly killed the multidrug-resistant gram-negatives Escherichia coli and Salmonella. They also worked better against stubborn gram-positive superbugs like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

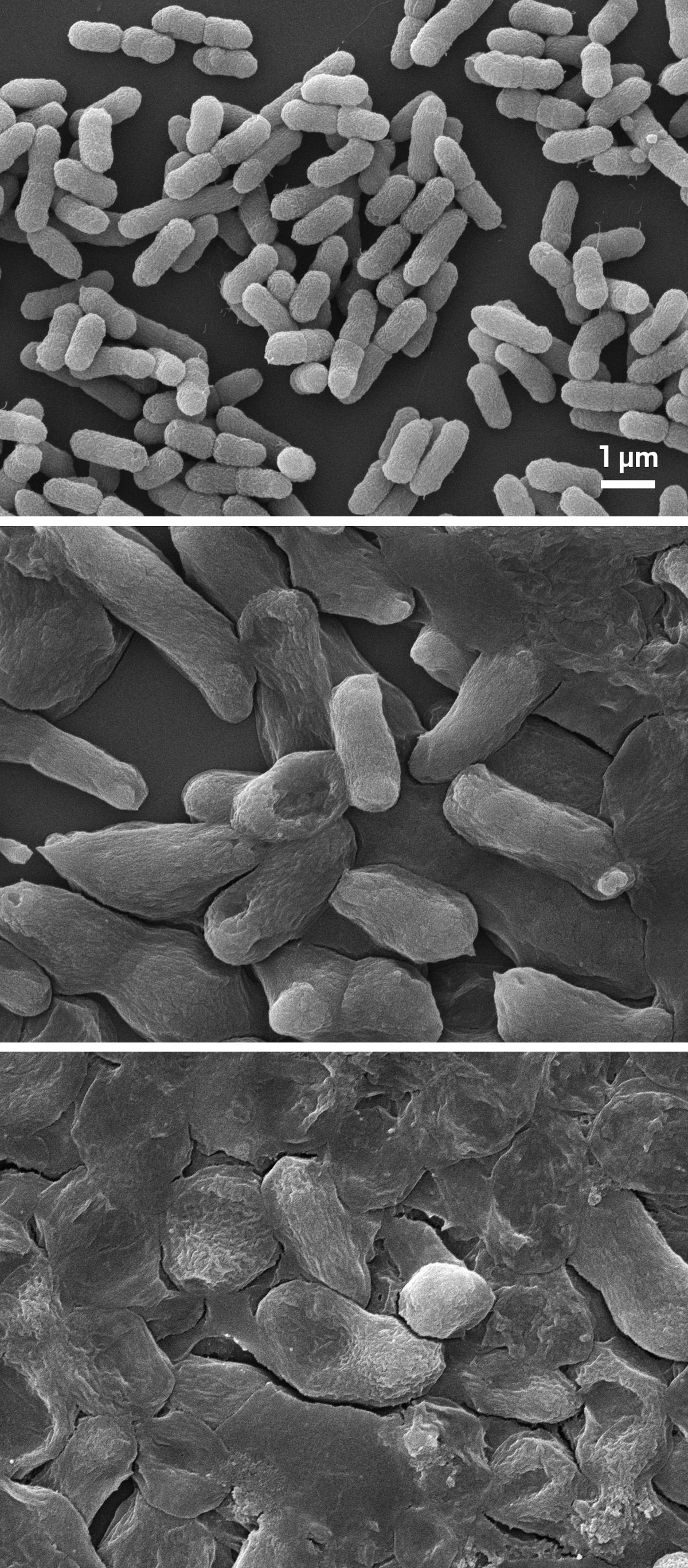

Scanning electron microscope images showing untreated, drug-resistant bacteria (top) and after being exposed to normal (middle) and high doses (bottom) of the vancomycin derivative. There is noticeable cellular damage with the higher dose.

Scanning electron microscope images of untreated, resistant Escherichia coli (top), after exposure to the vancomycin derivative at a standard dose (middle), and a four-times-higher dose (bottom).

Credit:

Dongliang Guan

“We were stunned by how robust the gram-negative activity was,” says Dongliang Guan, a medicinal chemist and the study’s senior author. He notes that treated cells piled up unused cell-wall building blocks—the same pattern seen when vancomycin successfully blocks wall construction—which showed that the drug reached its target.

In mice, the lead compound cut MRSA-associated mortality to zero and significantly reduced bacterial load in resistant E. coli infection by about 90–97% relative to untreated mice. It also maintained effective levels in the bloodstream about 40 times as long as unmodified vancomycin, thus helping another antibiotic, meropenem, regain its punch against resistant E. coli.

Though the exact entry mechanism remains unclear, Guan likens it to a Trojan horse. The bacterial gatekeepers may mistake quinoline as familiar and think, “Oh, this is something we need—let’s let it in!” Guan says.

Jonathan Stokes, a biochemist at McMaster University who was not involved in the study, calls the effect a classic molecular property cliff, in which tiny structural changes unlock large functional advantages.

Guan’s team next wants to figure out exactly how the drug gets inside the bacterial membrane—whether it’s slipping through a specific protein gate or squeezing through temporary weak spots—and the researchers are now testing bacteria with targeted mutations to pinpoint the route. They’re also tweaking the quinoline to see if the effect can be extended to other gram-negative species, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which remained largely unaffected.

Both Lewis and Stokes think the work’s broader lesson is that systematically testing and understanding subtle, creative modifications to existing antibiotics could reveal more gain-of-function effects and help researchers progressively expand the reach of the drug classes already available.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2025 American Chemical Society