Long Distance hiking is hard work. Everyone knows that, but it is still a shock to actually do it compared to thinking about doing it. After we had completed a few hundred miles, friends would text us with encouragement fused with amazement. They often commented that “you must be in amazing shape!” We always laughed. We were much better able to do the work we set out to do after several weeks of doing it, but neither of us would have categorized ourselves as being in “amazing shape.” Honestly, between the dings and bumps of everyday life on the trail, bugs, cold, heat, and hunger, it was actually difficult to logically asses whether or not we were in “amazing shape.”

I remember feeling similarly about my fitness in 1975. I walked nearly three times as far then (~1500 miles) as we did this trip (666.5 miles). I remember being able to pack on more miles with less thought (e.g. trail legs) but I never thought of myself as a specimen of great fitness. I just walked. And it hurt. And it was hard. In 2025, it was the same. We just walked, and it hurt, and it was hard.

And it was worth nearly all of the effort. There were days or sections (here’s looking at you, Roller Coaster), or moments, like crossing the unprotected 6 lane highway in Daleville, VA, that were not fun. Sometimes it was easier to curse the trail builders or cry a river of tears to fill up the creeks than to put one foot in front of the other. But, put one foot in front of the other, we did. Those who reach their long-distance hike goal often reach them physically and emotionally depleted. Some are overtrained and burned out but others have just enough. A few–or perhaps just one amazing woman, Pegleg–have energy left over.

To a person, most say it was more than worth all the effort. Many want to hike more trails. At our age, would we do it again? Yes. We may titrate the length of our hikes–a whole PCT is unlikely at our ages–but The Long Trail beckons and we will answer as long as we can put one foot in front of the other without putting other’s at risk.

What Is In This Blog

This is another data-heavy blog for the random geek who is interested in it. There is a message for all hikers, and that is that paying attention to your body is part of the journey. Yes, you need the “Big Three” and you need navigational tools. Your shoes should fit and you need proper clothes for the season in which you are hiking. Yet, it is your body and mind that run the show. Maybe it is easy to forget this because so may thru hikers are young and fit and have a wide margin of tolerance between dead and healthy. Maybe it is because, as a group. we distance hikers are a stubborn lot and we rarely give in even when perhaps we should.

We collected mountains of data using commonly available fitness watches (Garmin Fenix 7, Fenix 8 and Samsung Galaxy 4). We monitored our fitness data, largely because it is interesting to us. I think we could have finished our hike and meet my goal of completing the Appalachian Trail with none of this data, but having it was both helpful and interesting. Perhaps more interesting to me, than The Historian, but still useful for both of us. For example, when our sleep scores were low, or we were struggling keeping our energy/body battery scores up, we were prompted to look at both our behaviors and the terrain to consider how we could improve things. I think this fed into injury prevention, something all of us care about. I am not saying you need a watch to prevent injury, but for us, at least, monitoring the data helped us stay focused on the magic that keeps one hiking: balancing the body’s ability, with the fuel it needs, and the demands the hike makes.

You can see how we collected data in the sister blog to this one, Post-Hike Nutritional Analysis: High Quality, Nutrient Dense Trail Food Matters.

Measures of Physical Capacity

Vo2Max

VO2 max is the maximum amount of oxygen your blood can circulate to your muscles during exercise. The oxygen uptake is measured in milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of weight per minute. Although a truly reliable measure is obtained by analyzing inhalations and exhalations during exercise, most fitness wearables provide a reasonable estimate.

Vo2Max is a well-researched measure of cardiovascular fitness. Most people’s Vo2Max peaks in their 30s and drops about 5%to 10% per decade.(1) On average, athletes, regardless of age, have a higher V02Max than sedentary individuals. Vo2Max is generally 15%-30% higher in men than women, due to factors like greater muscle mass, higher hemoglobin, and body fat differences. Training narrows that gap.

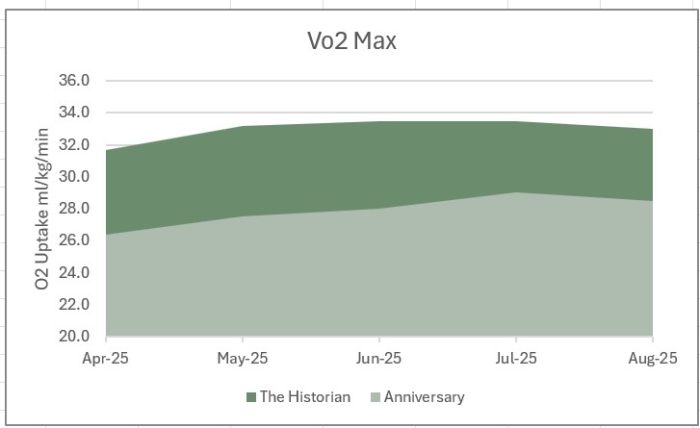

Both of us rated above average at the start of the hike, and ended the hike in the very good range. The Historian’s V02Max had increased within the first month. I (Anniversary) trailed his performance increase, not rising into the very good range until month two. My Vo2Max continued to increase until we ceased hiking, The Historian’s peaked and held steady until we stopped hiking. Both of us saw a small decline in the month after leaving the trail.

Threshold Heart Rates

“Threshold heart rate (THR) is the highest intensity you can sustain for a long time (around an hour), often defined as the point where lactate starts building up faster than your body can clear it, typically around 85-90% of your Max HR.”(2) Psychologically, it is the heart rate that if you pass it, your body tells your mind, “I have to stop.” I watch my threshold heart rate closely as it is directly associated with my ability to actually enjoy hiking. Finding the “sweet spot” just south of your THR, is the place where you can keep going for hours and is exactly what pays off for distance hikers.

We climbed the Three Ridges section twice. When we were almost to the top of the 3,000 foot rocky scramble, we discovered The Historian’s phone was still sleeping peacefully in the shelter below us. In an effort to beat the heat on the intense climb, we had left early and in the predawn light, did not see the phone lying on the shelter floor. Trying to get ahead of the sun, we also hiked harder than usual, pushing past our threshold. With the effort and the humidity, the first time we climbed the ridge we felt awful. Nausea, sweat, and pressure. After climbing down and retrieving the phone, on the second pass on the hill we slowed down fractionally, and while it it sucked to have to climb it again, and the temperatures were rising, both of us did better. Curiously, it took less time the 2nd trip because we stopped less.

Like heart rate in general, the LHR is age-related and drop with age. Also, people who established a high THR earlier in their life, when the heart was more plastic, may sustain higher rates than those who begin training later in life. I track my threshold (mostly for Nordic skiing) and can reliably say that it did not change from its usual as a result of the AT. People who are not active can often increase their threshold heart rate by taking up an exercise program.

For those of you who would like to estimate your THR, you can use the Norwegian University of Science and Technology heart rate calculator to estimate your maximum heart rate and then take 85% to 90% of that for your THR. This method is far superior to the traditional 220 minus your age, which typically yields underestimates for older adults.

Resting Heart Rate

Resting heart rate is a durable measure of overall current and future health. Although there are people with low resting heart rates caused by ill health, in general, lower resting heart rates are indicative of better health.

The Historian has a famously low heart rate that always sends health professionals who don’t know him for the defibrillator. During most of his time on the trail, his resting heart rate dropped 2 to 4 beats from his baseline of 44 beets per minute. Anniversary’s resting heart rate showed a more variable pattern while on the trail, dropping off and on, generally associated with the quality of sleep on any one night.

The first month off trail, both of us saw a small increase in resting heart rate. As we became more rested, we both returned to our pre-hike baselines, 44 for The Historian and 56 for Anniversary.

Heart Rate Variability

Heart Rate Variability is a measure of the variability between intervals of consecutive heart beats. It is a good indicator of health, and even predictor of death.(3) HRV is a measure of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) which is composed of the sympathetic (fight or flight) and parasympathetic (rest) systems. A higher HRV indicates a more flexible, stress resilient cardiovascular system.

HRV varies with age, lowering as a person gets older. This important measure of health is available on fitness gadgets. Increasingly, athletes use it as a measure of training status. Sudden deviations from one’s own mean can be an indication of overtraining or illness. For example, it was this measure that alerted me to the fact that I had a severe infection last winter. The symptoms I felt were vague, mostly fatigue. When I tried to rest and the HRV did not recover, we went for medical care. A biopsy revealed a life-threatening infection. Having the HRV data allowed us to identify it earlier, thereby allowing a more conservative treatment plan. Needless to say, we pay attention to our HRV.

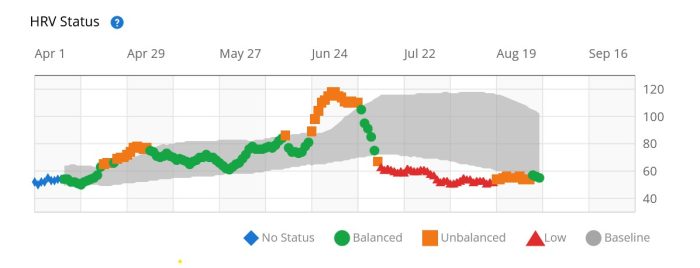

Reviewing The Historian’s data, we can easily see the point where he falls into the overtraining state. His personal experience, and the data together confirmed that he was running out of hiking “gas.” He was exhausted and not recovering. We ruled out illness, ruling in both nutritional challenges and simple exhaustion. After a month of rest and extra nutrition, he is returning to his pre-hike baseline.

My HRV zoomed up (healthier) when we hit the trail. I always sleep/relax better outdoors than in. I dropped below my own baseline in May when I fell into the creek and was having so many feet problems. There was another blip when the heat was making it hard to sleep, but I generally did well on the Trail. When we left, my HRV dropped down but returned to pre-trail baseline after a few rest weeks. The drop post-hike corresponded to me feeling worn out and stressed trying to return to our usual chores.

Endurance Score

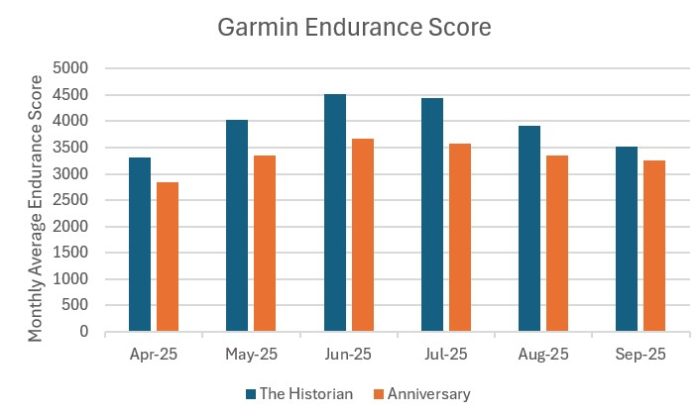

Garmin fitness watches provide an endurance score. It is largely derived from your VO2Max, but also includes other activity-related information. It has no inherent meaning, except that there are tables to which you can compare, and more importantly, you can follow your own pattern across time. More exercise does not mean more endurance, if that exercise is past your capacity.

The Historian’s scores, even allowing for differences between men and women, is always higher than mine. I cannot explain why, but I am guessing it is related to my lungs. I got frostbite in my lungs 40 years ago while working a chairlift evacuation as a ski patroller, have a history of lung disease 30 years ago, and hereditary chronic low-level anemia. I am guessing together, those things put a damper on my VO2Max and endurance score. They do not put a damper on my experience, so I try not to get competitive about it.

The key point I see, in reviewing our data, is that The Historian’s proportional increase, and decrease, in endurance was more rapid than mine. This fits with our on-the-ground experience of him being faster and stronger earlier in the hike, and then experiencing a more rapid decline. We joke that I am an ox, I just plod along and always get stuff done, but he is flasher than I.

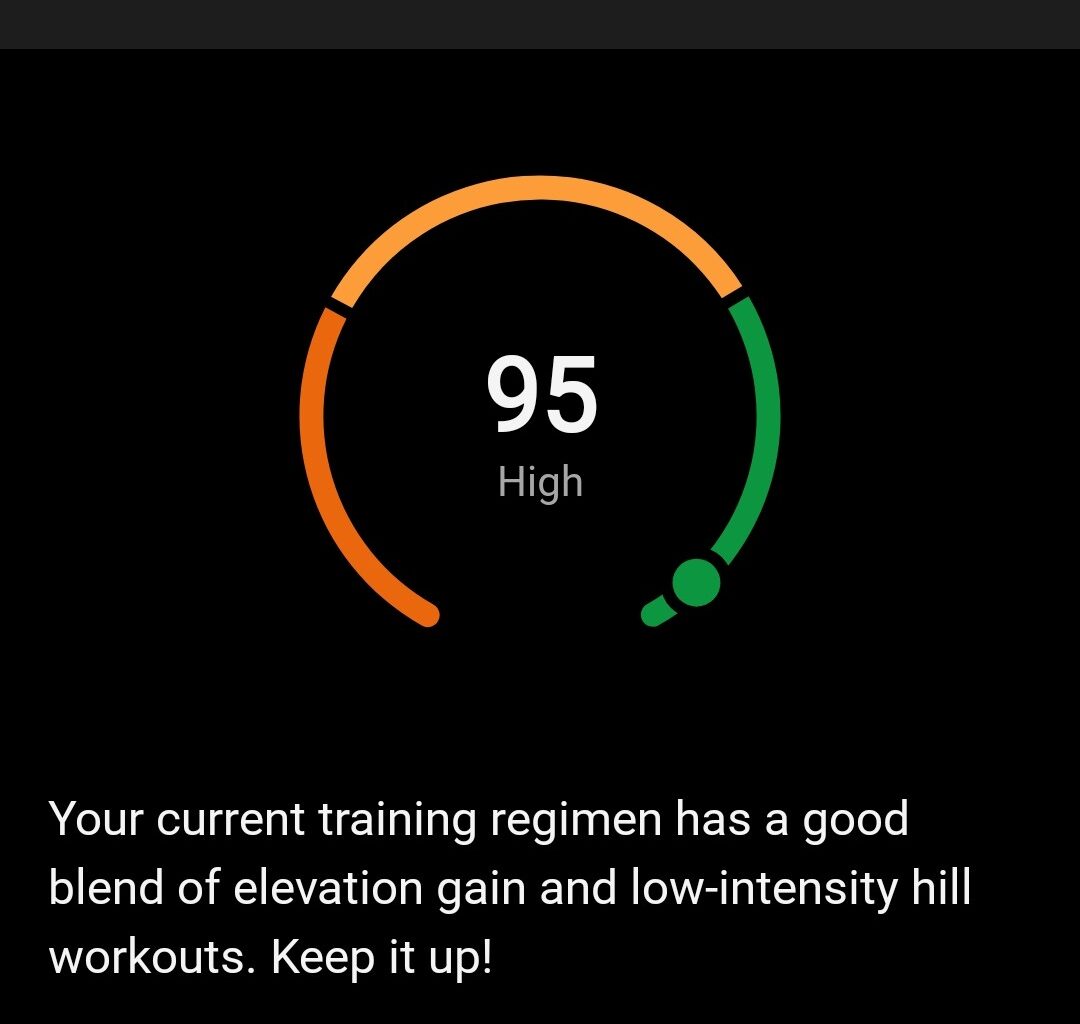

A month after we returned, Garmin added a hill score to my options. Although it has subsequently dropped as the post-trail months have increased, I almost maxed our their score on hill endurance. We both found it amusing. The narrative said I could improve by increasing the number of short, steep climbs I did.

Overtraining and Burnout

Overtraining is a major risk for long-distance hikers. The Historian ended his weeks on the trail limping along feeling dreary and tired. He needed more rest than he was getting for the work he was doing.We talked with other hikers who experienced overtraining. Fellow Trek Blogger Eddy “Late Start” Li even commented on his experience with it in one of our blogs.

For thru hikers, the constant high level of output can be hard to sustain. Chronically pushing the body to do more work than it is able to do leads to muscle loss and increases the risk of injuries, chronic fatigue, and hormonal imbalances. Although many distance hikers do not really think in terms of training like a competitive athlete, the constant work load of hiking places similar extreme demands on the body.

Overtraining can contribute to:

Muscle breakdown

Metabolic slowing

Hormonal imbalances

Increased fat storage

Signs of Overtraining include:

Chronic Fatigue, persisting for weeks

Performance Declines (e.g. harder to walk the same number of miles)

Frequent Injuries (falling more often or “tweaking” muscles and joints)

Changes in Mood, especially irritable, unmotivated, or feeling depressed

Increased Resting Heartrate

Changes in Heart Rate Variability

Illnesses due to a weakened immune system

Avoiding Overtraining and Burnout in Long Distance Hiking:

Zero and Nero days are not signs of failure, they are important to keep your body functioning

Fuel your body with adequate macro-nutrients (carbohydrates, proteins & healthy fats)

Stay hydrated, drink plenty of water, with an appropriate amount of electrolytes

Sleep: 7-9 hours of quality sleep is necessary for repairing the brain and the body from the previous day’s work

Listen to your body, or at least your fellow hikers. If you feel or look worn out, you probably are.

Fleg, J. L., Morrell, C. H., Bos, A. G., Brant, L. J., Talbot, L. A., Wright, J. G., & Lakatta, E. G. (2005). Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation, 112(5), 674-682.

Schultz, M. (n.d.) Does It Matter if Your Threshold Heart Rate is High or Low? Training Peaks. https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/does-it-matter-if-your-threshold-heart-rate-is-high-or-low/

Jarczok, M. N., Weimer, K., Braun, C., Williams, D. P., Thayer, J. F., Gündel, H. O., & Balint, E. M. (2022). Heart rate variability in the prediction of mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of healthy and patient populations. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 143, 104907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104907