It may sound like a bit of a stretch, but being more flexible could add years to your life. Our body’s ability to bend and flex gives us more than just the ability to touch our toes or claim bragging rights at a yoga class.

It keeps us mobile and healthy, and researchers are beginning to wonder if the effects could actually be profound.

A long-term study published in 2024 looked at people’s flexibility in middle age, testing the range of motion in their ankles, knees, hips, spine, shoulders, elbows and wrists.

When the study began 13 years ago, participants were given an overall score for flexibility, then tracked over the intervening years.

Researchers found that people with greater flexibility had a lower risk of premature death. The study observed the effect in both sexes, but it was stronger in women (who are also more naturally flexible than men).

Females with lower flexibility scores were nearly five times more likely to die across the study period. Males with lower scores were nearly twice as likely to die early.

What does it tell us? That it is, as the saying goes, better to bend than to break.

What is flexibility?

The team behind the study stress that their work doesn’t show a causative link between flexibility and mortality.

But the association between the two makes sense, says lead author Dr Claudio Gil S Araújo of Clinimex, an exercise medicine clinic in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

“We know that if you’re aerobically fit and strong, it’ll help you live longer,” he says. “Perhaps the same is true with flexibility.”

Araújo is cautious with his words because his study is one of surprisingly few that have looked into flexibility and long-term health outcomes.

“‘Sit and reach’ measures flexibility in the back half of your posterior chain: your glutes, your hamstrings, to a lesser extent your lower back” – Image credit: Shutterstock

“‘Sit and reach’ measures flexibility in the back half of your posterior chain: your glutes, your hamstrings, to a lesser extent your lower back” – Image credit: Shutterstock

In fact, flexibility itself is poorly understood and hard to measure – despite the fact that the American College of Sports Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana, ranks it as a key tenet of physical fitness.

The other tenets are muscular strength, muscular endurance, cardiorespiratory endurance (the ability for the heart and lungs to deliver oxygen to muscles) and body composition (the proportion of fat, muscle, bone etc).

In terms of a definition, flexibility is usually described as our ability to move pain-free through the full range of motion in a particular joint.

That could be raising our arms above our heads, or tilting our heads to our shoulders, or bringing our knees to our chests.

The most common measure of flexibility is something called the ‘sit and reach’ test.

You sit on the floor with your legs stretched straight out in front of you and your feet against a wall. Then, with one hand on top of the other, you reach down and try to touch your toes.

You’ll feel a stretch, but it won’t give you a complete picture of how flexible you are.

“‘Sit and reach’ measures flexibility in the back half of your posterior chain: your glutes, your hamstrings, to a lesser extent your lower back,” says Dr Lewis Ingram, a physiotherapist and researcher at the University of South Australia in Adelaide.

“But that doesn’t give me any indication of how flexible I am in the hip flexors, shoulders and other parts of my body. So that’s one problem. We can’t measure flexibility in a single test.”

Read more:

Limits and effects

Another problem, Ingram says, is that we’re not even completely sure how flexibility works anatomically. We know our muscles extend, and the tendons and ligaments stretch.

There’s a network of connective tissue called fascia that encases the muscles and probably has a role.

Genetics are a factor too, because they determine how much collagen and elastin – proteins that give your tissues strength and structural support – you have. Even the brain and the nervous system could be in play when you try to do the splits.

“There seems to be a big ‘software’ component to how flexible we are,” Ingram says. This may control the pain we feel when we stretch to our physical limits.

“It could be that our central nervous system stem puts on the brakes, not allowing us to go into a full range of motion.”

“Like a lot of things in health and fitness, flexibility is a case of using it or losing it” – Image credit: Getty Images

“Like a lot of things in health and fitness, flexibility is a case of using it or losing it” – Image credit: Getty Images

It’s a common assumption that flexibility is important for sportspeople and gym-goers. Lots of us stretch before or after workouts in the belief that it’ll improve our performance and recovery, or reduce our risk of injury.

But while flexibility undoubtedly increases our range of motion, its effects on performance and injury are complex. Patchy research gives us an incomplete picture of the ways stretching and flexibility affect athletic performance.

Ingram points to distance runners as an example. Having flexible joints and muscles may help a runner’s stride and reduce tightness after a run.

Conversely, being too flexible can reduce the stability of leg muscles and tendons, meaning less power return and, potentially, a greater risk of injury on the road.

Those factors will be different if you’re a gymnast and different again if you’re a weightlifter.

“So you need to ask if the benefit of the increased range is going to offset any potential reduction in strength or power,” Ingram says. “That will depend on the event level.”

The benefits of flexibility

For those of us who aren’t competition-level athletes, the benefits of becoming more flexible almost certainly outweigh the costs.

Desk jobs and sedentary lifestyles place restraints on our mobility and these exacerbate the way our body’s natural flexibility declines as we age.

“You start to lose flexibility almost from the very beginning of your life,” Araújo says. “A three-year-old kid will be more flexible than a 16-year-old. It’s like a biological clock.”

While flexibility undoubtedly increases our range of motion, its effects on performance and injury are complex – Image credit: Alamy

While flexibility undoubtedly increases our range of motion, its effects on performance and injury are complex – Image credit: Alamy

Unfortunately, unless we do something about it, this only gets worse. A study on hip and shoulder joints, for example, showed that people lost 6° in range of motion per decade after their 50s. In later life, our muscles also shrink and weaken.

Many of us begin to store more fat, which can restrict our movement. “But mostly it’s in the tendons and the joints,” Araújo says. “The tendons are more flexible when you’re younger.”

He speculates that this could partly explain why people with poor flexibility seem to have greater mortality rates.

Research has shown that flexibility can help manage pain, aid weight loss and prevent muscle wastage as we age. It can also help to increase mobility and autonomy in older populations.

These factors may combine in things like falls, which can be lethal in older people.

“If you get unsteady when you’re walking, you might not have the flexibility to recover,” Araújo says. “You might not have the flexibility to absorb the fall. And you might not have the flexibility to get up again.”

Another factor in long-term health is a surprising link between flexibility and the risk of heart disease.

A growing body of research shows that people with poor flexibility have increased arterial stiffness, a measure of how flexible the arteries are and a risk factor in cardiovascular disease.

Some studies have also shown that static stretching exercises – where you hold a muscle in an elongated position for a period of time – can reduce arterial stiffness, especially in middle-aged men.

“This is one health area where there’s been consistency,” says Ingram, who is in the middle of a literature review on the links between flexibility and health.

“Given that coronary heart disease is probably the single biggest killer in most high-income countries in the world, static stretching does seem to have an effect on that.”

Read more:

Increasing your flexibility

Like a lot of things in health and fitness, flexibility is a case of using it or losing it. The good news is that, whatever your age, you can make yourself more flexible, says Araújo.

“You have to train specifically for flexibility and you have to move outside your comfort zone,” he says. “But even if you [only] do a few minutes a few times a week, it’ll help.”

Studies show that different kinds of exercise can help. Practices like yoga and tai chi involve a lot of stretching and moving the joints in a full range of motion.

Ingram says strength training is effective because it makes your muscles “long and strong”, whereas static stretching doesn’t necessarily strengthen your muscles in an extended position.

A 2023 review even suggested that as long as you move to full extension when you lift weights, you might not need to stretch before and after the workout to reap the benefits.

Static stretching does, however, remain one of the most popular (and obvious) forms of flexibility training.

Whatever technique you opt for, the experts recommend that all of us make time for flexibility training – Image credit: Alamy

Whatever technique you opt for, the experts recommend that all of us make time for flexibility training – Image credit: Alamy

Earlier this year, Ingram and his colleagues published a meta-analysis, seeking to define exactly how much stretching you need in order to improve your flexibility. It’s not as much as you might think.

They found that there was no observable improvement in flexibility if you stretch for more than four minutes per workout or 10 minutes per week.

“The caveat is that’s per muscle,” Ingram says. “And it’s not to say that nine minutes or eight minutes per week doesn’t do anything. It’s just that every minute you do up to about 10 minutes seems to give you more.”

Where to start

If you’re feeling tight or you’re not sure where to start with flexibility, Ingram’s advice is to get an assessment from a physiotherapist.

“That way, you can find out if you actually need to stretch to improve your flexibility. And if you do, what muscles do you need to stretch?”

A physio might also suggest a different technique. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) is a trendy way to get bendy.

The technique is similar to static stretching, but usually requires an assistant, as you push against a stretch that they help you to achieve. This phase of the stretch is known as an isometric contraction.

The muscle generates force without changing length and the hope is that this unlocks a greater range of motion.

PNF has been around since the 1940s and intermittently researched and compared with static stretching. Some studies say it’s better, some say it’s not, most say both options are good.

“Anecdotally, I find it really powerful,” says Ingram. “You get a better bang for your buck than static stretching. But it hasn’t been put under the scientific microscope as much, so we don’t have guidelines to follow.

“How hard should I contract during the contracting part of the PNF? Should it be all-out? Should it be 30 per cent? Should it be 50 per cent? How long should I contract for? How long should I relax for? All those things are not well established.”

Whatever technique you opt for, the experts recommend that all of us make time for flexibility training, especially in middle age and onwards.

Ingram calls it the “forgotten child” of training, while Araújo says that there are easy ways to fit it into busy schedules, such as doing some stretches whenever your phone or smart watch tells you you’ve been sitting for too long.

Bottom line: we could all do with some flexercise.

Don’t be tight

Forget touching your toes. Dr Lewis Ingram offers four do-it-yourself tests that indicate how flexible you really are

1. Knee-to-wall

Tests your: ankle flexibility

Image credit: Acute Graphics

Image credit: Acute Graphics

Stand with your big toe 5–10cm (2–4in) from a wall and bend your knee to try and touch the wall. If you can, move your foot back until you reach a point where you can just touch the wall before your heel lifts up.

“8–10cm (3–4in) is a good distance. Shorter than that would suggest you’re a bit tight,” Ingram says. “It’s also important that you’re roughly equal on both sides because an imbalance can cause other problems.”

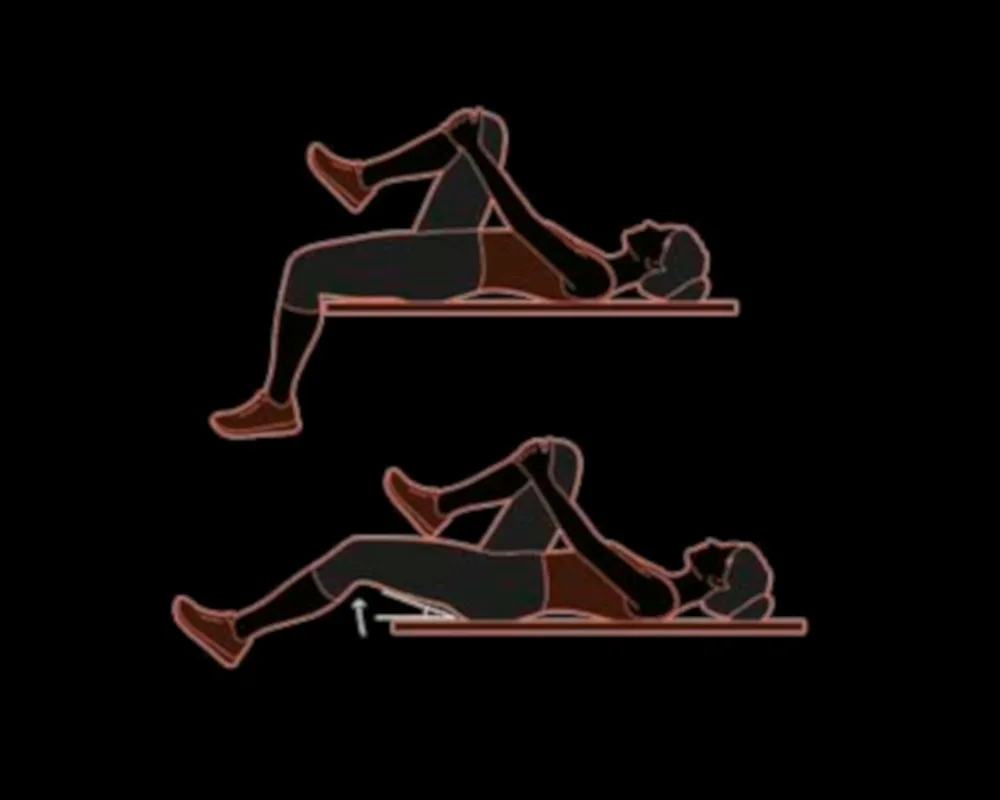

2. Leg raise

Tests your: hamstrings

Image credit: Acute Graphics

Image credit: Acute Graphics

Lie on your back and, while keeping your leg straight, lift it off the ground (it’s helpful to have someone to support it). Lift until you feel a tightness, then measure the angle from horizontal.

“80° and above seems to be okay. Anything below 70° or 60° seems to be limited,” Ingram says. Do the test with both legs to check for imbalances.

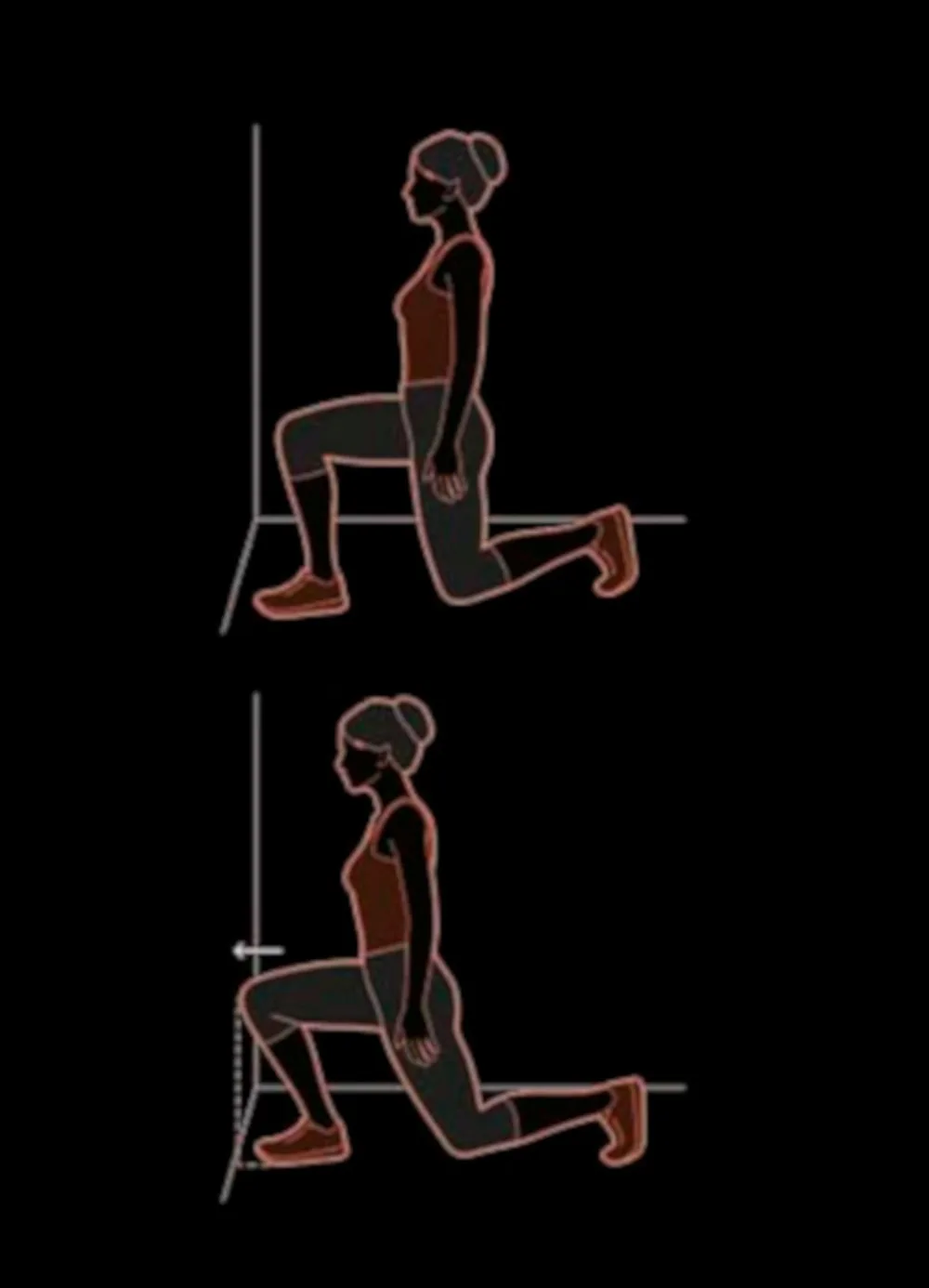

3. Thomas test

Tests your: hip flexors

Image credit: Acute Graphics

Image credit: Acute Graphics

This is a fiddly test, so you may want to ask someone for assistance or see a physio.

Sit on the edge of a bed or seat. Bring one knee to your chest, then lie back, letting your other leg hang down over the edge of the bed.

Now look at how the upper part of the hanging leg lies. “If it doesn’t make horizontal, it’s potentially a bit tight. If it goes below horizontal, then it’s probably okay.”

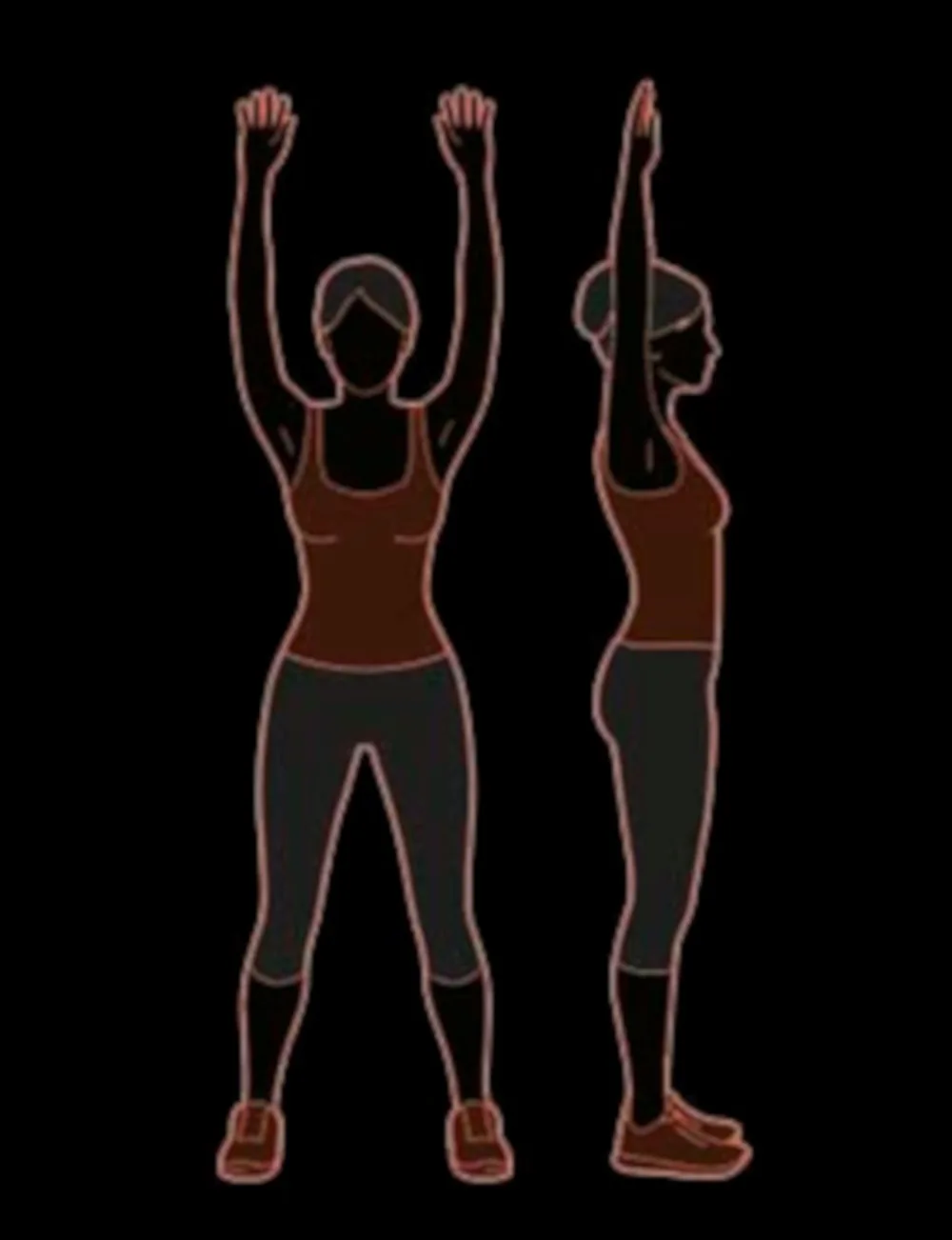

4. Overhead arm extension

Tests your: lats and pecs

Image credit: Acute Graphics

Image credit: Acute Graphics

To test overhead mobility, stand with your back against a wall and extend your arms above your head. Can your hands touch the wall? “If they can, you’re probably okay. If not, you’re probably limited through your lats.”

Now stretch your arms out to the sides and bend your elbows to 90° with your hands up straight. “Can you get your wrist to touch the wall? If you can, that’s good. If not, you’re probably tight through your pecs.”

Read more: