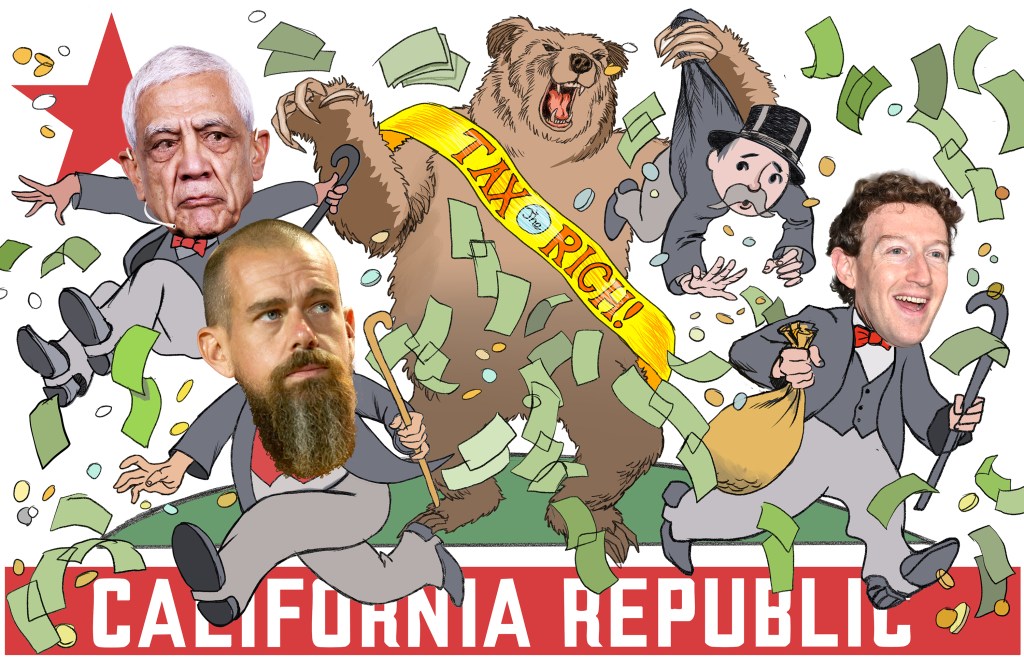

When billionaire venture capitalist Vinod Khosla publicly branded Rep. Ro Khanna a “commie comrade” over the weekend, it was more than a personal jab — it was a sign of how fiercely a new proposal to tax California’s billionaires is dividing Silicon Valley and the state’s political class.

The proposal, which would impose a one-time “emergency tax” on the net worth of California residents worth more than $1 billion, is roiling some of the Bay Area’s havens for the ultra-wealthy and setting off a vitriolic political fight over how far the state should go to fund its health care system — and whether the super-rich will tolerate it.

RELATED: More than half of California’s billionaires call the Bay Area home: Who are they?

Over the weekend, anger among some of Silicon Valley’s most affluent hit a crescendo, with Khosla attacking Khanna for supporting the initiative to put the tax on November’s ballot

Of the roughly 200 billionaires in California, more than half call the Bay Area home.

Topping the California billionaires list, according to Forbes, are the founders and leaders of Silicon Valley’s technology giants — Larry Page and Sergey Brin of Google, Mark Zuckerberg of Meta and Jensen Huang of Nvidia — along with a constellation of venture capitalists and crypto executives.

Many live in some of the nation’s wealthiest enclaves, from Atherton and Hillsborough to Portola Valley.

Khosla, a Sun Microsystems co-founder and early investor in Google and Amazon, lives in Portola Valley.

But now, the Service Employees International Union–United Healthcare Workers West has poked a gilded hornets’ nest with a proposed ballot initiative to take a 5% bite of each billionaire’s wealth — including publicly traded stock and private holdings that are not always easy to cash in. The levy could be paid over five years, with an annual fee of 7.5% of the remaining balance.

Supporters say the measure, known as the California Billionaires Tax Act, could send as much as $100 billion into state coffers, to help stabilize a health care system facing a massive funding shortfall.

They argue the hole was created by President Donald Trump’s new budget bill, which cuts billions in federal spending while tightening Medicare and Medicaid eligibility. Without new revenue, proponents contend, California would be forced to slash services or shift the burden onto ordinary taxpayers.

Authors of the proposal said in a report that the collective wealth of California billionaires skyrocketed from $300 billion in 2011 to $700 billion in 2019 to $2.2 trillion as of last October. Meanwhile, they wrote, billionaires now pay a far smaller share of their wealth in taxes than they did when Ronald Reagan was president.

“It’s not some gigantic amount that we’re asking for,” said Darien Shanske, a UC Davis School of Law professor and one of the proposal’s authors. “It’s not a lot of money for people in this class.”

Russell Hancock, CEO of the think tank Joint Venture Silicon Valley, said that on first blush the proposal might seem a slam dunk.

“Silicon Valley’s an economy that mints millionaires and billionaires, and a lot of them,” Hancock said. But, he added, “does it actually come back to haunt us?”

The state Legislature’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office projected the tax could generate tens of billions of dollars beginning in 2027 and spread over several years. But it warned “it is likely that some billionaires decide to leave California,” potentially costing the state hundreds of millions of dollars or more each year in lost income taxes.

Proponents expect the measure to raise $100 billion from 2027 to 2031. The Legislative Analyst’s Office cautioned, however, that the amount is highly uncertain because billionaires could restructure their finances to reduce their exposure and because much of their wealth is tied to volatile stock prices.

Critics of the proposal point to reports that Page and Brin have begun shifting business operations out of state. Would-be founders, they warn, could take their ideas and startups elsewhere.

“This is stupid tax policy,” said John Grubb, interim CEO of the Bay Area Council, which represents businesses including major technology firms. “It drives capital and people out of the state, shrinks the tax base and leaves everyone else paying more for fewer services.”

Silicon Valley startup guru and Stanford University adjunct professor Steve Blank called the tax “a self-destructive act” that would “strangle innovation in its crib.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom and San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan, who is weighing a run for governor, have both attacked the proposal, saying it would harm California as a single state acting on its own.

Silicon Valley Democratic Rep. Khanna, however, said Californians “must balance Silicon Valley’s engine of prosperity while ensuring that we don’t abandon millions who won’t have health care because of Trump’s tax bill, and hundreds of thousands of nurses and home care workers who will be laid off.”

The congressman, who attributed Democratic-donor Khosla’s “commie” jab to “passion for Silicon Valley,” cited UC Berkeley researchers’ findings that the wealthier a person is, the lower their effective income tax rate — largely because most wealth is only taxed when assets are sold.

A provision in the proposal would allow holders of illiquid assets, such as startup equity and stakes in private companies, to defer taxes until they take money out of those investments.

David Lesperance, a tax and immigration lawyer who advises ultra-wealthy clients, said he has already helped three Silicon Valley billionaires leave California to escape the potential tax.

The proposal was filed with state authorities the day before Thanksgiving. Should it pass, any billionaire seeking to avoid the tax would have had to establish legal residence outside California by Dec. 31 of last year — just a month later.

“Over Thanksgiving, people really started reading it and going, ‘Oh, oh, oh,’” Lesperance said. “It was a pretty frantic December and it’s been fairly frantic ever since.”

Whether such moves would succeed remains an open question. California’s Franchise Tax Board is known for aggressively challenging claims of out-of-state residency.

Guidelines show the agency considers how much time a person spends outside California, where their family and primary home are located, the location of bank accounts and doctors, permanence of work in the state and even affiliations with churches and country clubs.

If the board rules that someone claiming to have moved out of state by Dec. 31 lacks sufficient evidence, “they’re totally on the hook for the tax,” Shanske said. “The notion that this is some simple thing, that they’re calling in from their Miami penthouse and therefore they’re done, that’s not true.”

Shanske dismissed predictions of mass billionaire flight, citing research showing relatively few wealthy households relocate in response to new taxes. Nvidia’s Huang, for one, has signaled little concern, telling Bloomberg he is “perfectly fine with it.”

Grubb, of the Bay Area Council, said the tax is not the right remedy for the health care budget gap.

“One solution,” he said, “would be to attract more high net worth individuals to move here rather than encouraging them to leave.”

Many critics fear a slippery slope that would deter innovation in California more broadly by targeting wealthy people who aren’t billionaires.

“It’s very easy to imagine that if this ends up on the ballot that there’s another initiative on the ballot next year that’s $100 million,” Blank said, “and the year after that it’s $50 million.”