This study supported one of our three hypotheses: the stringency index reduced access to hospital services across the four geographical regions. However, the number of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases and vaccination policies had a limited impact on hospital accessibility. The first lockdown led to a significant decline in outpatient numbers, whereas the second did not show an obvious reduction, even during the peak pandemic period. Services that were not urgently required, such as testing, experienced a significant decline during the pandemic. There were notable differences among the hospitals. For example, in Lira, almost all services except ART were significantly affected by the three indexes, whereas Naguru experienced fewer disruptions than the other three RRHs.

Difference between first and second lockdowns

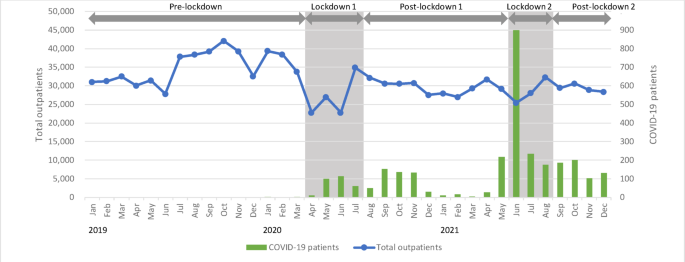

The timing, duration, and impact of the first and second lockdowns varied. The first lockdown, which imposed strict travel bans and public health measures (stringency scoring at 93.5 points), took place when the number of infectious cases was still low and lasted for nearly five months. Restrictions were gradually eased as COVID-19 cases began to rise. A previous study in SSA observed that earlier lockdowns, compared to those in other regions, allowed countries to strengthen infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, enabling them to better manage the pandemic when the number of cases was low4. In contrast, a global analysis suggests that the effects of strict behavioral restrictions during the first year of the pandemic diminished over time due to factors such as fatigue, prolonged infection spread, and lack of adequate support22. This study also found that the effectiveness of severe lockdowns was not as significant as the spread of the infection itself. This may be because people, tired of the strict movement restrictions, became more socially active as a form of reaction.

In the second lockdown, severe restrictions were imposed immediately following a sharp increase in the number of new confirmed cases by the Delta variant, and the level of restrictions was maintained at a stringency score of 70 points for approximately six months. The subsequent decline in new infections after the second lockdown suggests that the restrictions had a certain degree of effectiveness. However, according to our previous studies, many individuals reported experiencing intense fear of death during the second lockdown, as they were surrounded by infected individuals and frequently witnessed the deaths of family members and acquaintances5,23. These findings suggest that people may have voluntarily limited their contact with others and avoided activities due to fear of infection. Overall, the effectiveness of lockdowns in reducing mobility and virus transmission diminished over time, largely due to pandemic fatigue.

In Uganda, the third wave, which began in December 2021, was characterized by the replacement of the Delta variant with the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa24. If the Omicron variant had been better understood in Uganda and more stringent mobility controls had been implemented, the spread of the third wave may have been less severe25,26. These insights emphasize the need for more flexible and targeted approaches to pandemic management in the future.

COVID-19 vaccination and its effectiveness on health service accessibility

The vaccine policy index was substituted to assess the effectiveness of vaccination on hospital access. COVID-19 vaccination in Uganda began in March 2021 and was made available to the entire general population in August 202115. Vaccination coverage stagnated in one quarter but reached 40% by December 202115. However, by this time, the Omicron variant had already replaced the Delta variant as the dominant infectious agent24. Regarding the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, the general consensus is that the vaccine provides less protection against Omicron compared to Delta, although booster doses have been shown to enhance effectiveness24. In Uganda, booster doses had not yet been widely administered to the general population at the time of this study26. Since this study covered the period only up until December 2021, it provides an insufficient timeframe to assess the efficacy of the vaccination fully. Several studies have reported that COVID-19 vaccine policies and their implementation significantly influenced health service utilization, including helping to mitigate disruptions in access to other health services27,28. Further studies with extended periods are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of vaccination and other associated factors in Uganda.

Despite the limited study period, our results indicate that the improved vaccine policy enhanced accessibility to certain hospital services, such as delivery, ANC, diabetes care, and immunization. For instance, delivery rates increased with higher vaccine index scores, particularly in Kabale and Soroti, and ANC uptake rose in Lira. This suggests that vaccine dissemination helped reduced the fear of COVID-19 in healthcare facilities among expectant mothers. Additionally, the number of clients seeking diabetes and child immunization services returned to pre-lockdown levels following the availability of the vaccine to the entire population, likely due to reduced fear of COVID-19 or the need to address worsening chronic conditions requiring urgent care. Further studies analyzing hospital medical records are needed to verify these health trends. Additionally, numerous studies have highlighted the impact of vaccine hesitancy on vaccine uptake in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)23,29,30. Understanding the relationship between people’s behaviors regarding access to essential health services, vaccine policies, and vaccine uptake requires more comprehensive research.

Differences by type of services

Overall, the stringency index harmed the uptake of various health services. By service type, delivery, ANC, and the two types of testing services were most adversely affected by the stringency index. Notably, HIV testing saw a significant decline during the first lockdown, with a 43.8% reduction compared to pre-lockdown levels, although ART provision continued. A substantial reduction in HIV testing was observed in many African countries31,32. This decrease may be attributed to the fact that HIV diagnosis, which often causes hesitation even under normal circumstances, was further avoided during a period of stringent behavioral restrictions.

Additionally, previous studies have reported the withholding of regular checkups by expectant mothers, delays in examinations for fetal abnormalities, and an increase in home deliveries11. A similar pattern of withholding of checkups among expectant mothers was observed in this study. These findings suggest that maternal and fetal deaths due to the “three delays”—delay in recognizing the problem and deciding to seek care (First Delay), delay in reaching a healthcare facility (Second Delay), and delay in receiving quality care at the facility (Third Delay)33—may have occurred nationwide, although detailed statistics are lacking11. Further robust statistical analysis using death certificates is needed to confirm this.

Regarding ART, our findings indicate that the stringency index had no significant effect on the uptake of ART services. This may be due to the continuity of care, including outreach programs by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), as highlighted in previous studies11,34,35. Similarly, childhood immunizations were also not associated with any of the three indices in this study. However, various studies in LMICs have reported a significant reduction in the uptake of routine childhood immunizations due to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns36,37,38,39. Despite this, our preparatory interviews revealed that the outreach vaccine team at Kabale RRH continued operations during the COVID-19 lockdown. The outreach programs for both ART and childhood immunization may have helped mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 transmission and travel restrictions.

This study focuses on RRHs, the top regional referral hospital, which served as the center for testing and treatment for COVID-19 during the pandemic. However, it also served as the essential health service delivery point for the majority of the population5. During the pandemic, the Ugandan Government delivered messages encouraging the public to use lower-level and near health facilities, such as health center IVs, IIIs, and IIs40. In our previous study, however, only 12% of respondents sought alternative care at lower-level public health centers, 17% shifted to private hospitals, and 18% discontinued treatment entirely5. Given these facts, it can be inferred that interruptions in access to the RRHs are unlikely to have been compensated for by other facilities and are more likely directly linked to the disruption of necessary treatments.

Differences by hospital/geographical characteristics

The stringency index exerted a more pronounced negative impact on service uptake across all hospitals compared to the other two indices. Comparing by hospital, Lira was negatively affected by stringency in five out of seven services, and Kabale was affected in four services. In contrast, Naguru and Soroti were less impacted by stringency. A key difference between the two groups is that Lira and Kabale are located in rural areas with relatively low population densities, whereas Naguru is situated in Kampala, the capital city, and Soroti is in a regional hub with high population density and heavy population influx.

In general, a tendency to avoid seeking medical care due to the fear of COVID-19 infection has been noted41. A study in Japan also suggested that fear of infection and discrimination against infected individuals were more pronounced in less urbanized areas42. Our previous study in Uganda revealed a situation where residents of a remote island refused to use a health center that had treated a COVID-19 patient, leading to the closure of the facility. A preparatory study for this study also indicated that in Lira, where there was significant stigma against COVID-19 in the community, a social psychiatric team from the RRH, consisting of psychiatrists and social workers, went into the community to conduct educational activities and provide mental health support for COVID-19 survivors, their families, and community members. This initiative helped reduce misunderstandings and stigma, resulting in an increase in the number of patients visiting the RRH5,43. These findings suggest that fear of COVID-19 infection in health facilities, along with the strength of stigma in rural Uganda, discouraged people from seeking health services11.

Naguru, located in Kampala, presents another unique situation. According to staff providing reproductive health services at the hospital, Naguru may have been less affected by the lockdown due to its proximity to a large slum within walking distance. The slum accounts for a significant proportion of the hospital’s outpatient visits, even under normal circumstances. Additionally, as Naguru is a national referral hospital covering a wide area, it receives many pregnant women with complications due to the “three delays”11. These factors likely limited the decrease in the number of patients seeking delivery and ANC services, providing a possible explanation for the smaller decline in patient numbers.

Recommendations

Prolonged lockdowns often lead to public fatigue and diminished effectiveness over time. Therefore, it is essential to adopt a flexible approach to the timing, geographic scope, and type of lockdowns, guided by close monitoring of the disease’s transmissibility and the preparedness of infection control systems. To support this, governments must continuously gather up-to-date information on emerging infectious diseases from both domestic and international sources.

This study, along with previous research, indicates that one of the primary reasons individuals refrained from seeking medical care during the early stages of the pandemic was fear stemming from misinformation and stigma. To address this, community outreach and health education activities led by RRHs and other key medical institutions were effective in alleviating public anxiety. For novel infectious diseases, timely and accurate information dissemination, along with psychological support, is essential to mitigate fear and encourage appropriate health-seeking behavior.

With regard to vaccination, our findings suggest that more rapid, equitable distribution of vaccines—as well as timely administration of booster doses (e.g., for the Omicron variant)—was needed in response to COVID-19. For future pandemics involving novel pathogens, it is crucial to strengthen global research collaborations, information-sharing mechanisms, and vaccine delivery systems, as different pathogens will require tailored responses. Furthermore, given the ongoing burden of various infectious diseases in Africa, there is a pressing need to establish regionally grounded, autonomous systems for research, vaccine development, and production.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although the study targeted one hospital from each of the four regions across the country, regional differences in COVID-19 responses and perceptions limit its representativeness. In addition, public health facilities that provide essential health services include district hospitals and health centers under the RRH, and it is thought that these subordinate health facilities supplemented the provision of essential health services as the RRH strengthened its acceptance of patients with COVID-19. Therefore, there are limitations in evaluating access to healthcare based solely on the number of outpatients at RRHs. Finally, the fact that COVID-19 vaccination in Uganda began in March 2021 means that the index is a weak indicator for evaluating its effectiveness during the entire pandemic. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to assess the determinants of hospital accessibility and their effects in Uganda during the COVID-19 pandemic.