Testing exercise is “money down the drain” and won’t advance understanding of Long COVID, experts say

Artistic depiction of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) symptoms by Jem Yoshioka, CC BY-SA 2.0

Artistic depiction of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) symptoms by Jem Yoshioka, CC BY-SA 2.0

Key points you should know:

A swath of low-quality exercise studies are used as justification that the intervention works for Long COVID; however, the studies included in those analyses neglected to account for PEM.

Less than 15% of Long COVID clinical trials testing the benefits of exercise or cardiopulmonary rehabilitation measured post-exertional malaise, according to their trial registration, while a handful excluded participants who experience it.

Some experts question the utility of these trials for Long COVID. However, the principal investigators running RECOVER-ENERGIZE, which is testing cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, declined to explain the rationale behind their study.

Experts say it is important to use multiple measures, including surveys and a two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test, to track PEM. Researchers say it’s important to track PEM for up to a month after the trial ends.

Despite the disproportionate focus on it as an intervention, exercise does not mechanistically connect the main pathophysiological findings or suspected mechanisms that leading Long COVID researchers are pursuing.

After several weeks of physical therapy, an anonymous patient from the University of Washington’s Long COVID clinic wrote that they had been left with “crushing fatigue,” making it hard to enjoy their hobbies, work, or take care of themself. Like many patients at Long COVID clinics across the world, they were prescribed graded exercise therapy (GET) to gradually increase their activity levels. Instead, it led to a crash.

For up to half of people with Long COVID, activities like exercise can trigger post-exertional malaise (PEM), a pathological process that leads to worsening symptoms.

Yet Long COVID clinics around the world are offering exercise as treatment while dismissing its serious harms. They also fail to connect it with most of the pathological findings seen in people with disease, or with leading ideas for symptom drivers, including immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, or viral persistence. The studies they use to justify its effectiveness are often biased and low quality, and sometimes they don’t even include people with Long COVID.

Researchers are following in the footsteps of clinicians who continue to offer these treatments for PEM in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), contrary to a lack of evidence. Still, despite loud and frequent criticism from patients and many experts, these studies continue.

According to an analysis conducted by The Sick Times, PEM is systematically neglected in research trials testing exercise interventions that could trigger it. Dozens of low-quality trials on exercise in Long COVID haven’t provided any answers and potentially harmed trial participants, and many never ended up publishing their results.

The flawed idea central to these trials is that exercise is a panacea, and gradually increasing it could treat Long COVID, Jaime Seltzer, researcher and scientific director of the advocacy group #MEAction, told The Sick Times. As a result, the research won’t advance our understanding of the disease’s actual underlying mechanisms, said Seltzer, calling it “money down the drain.”

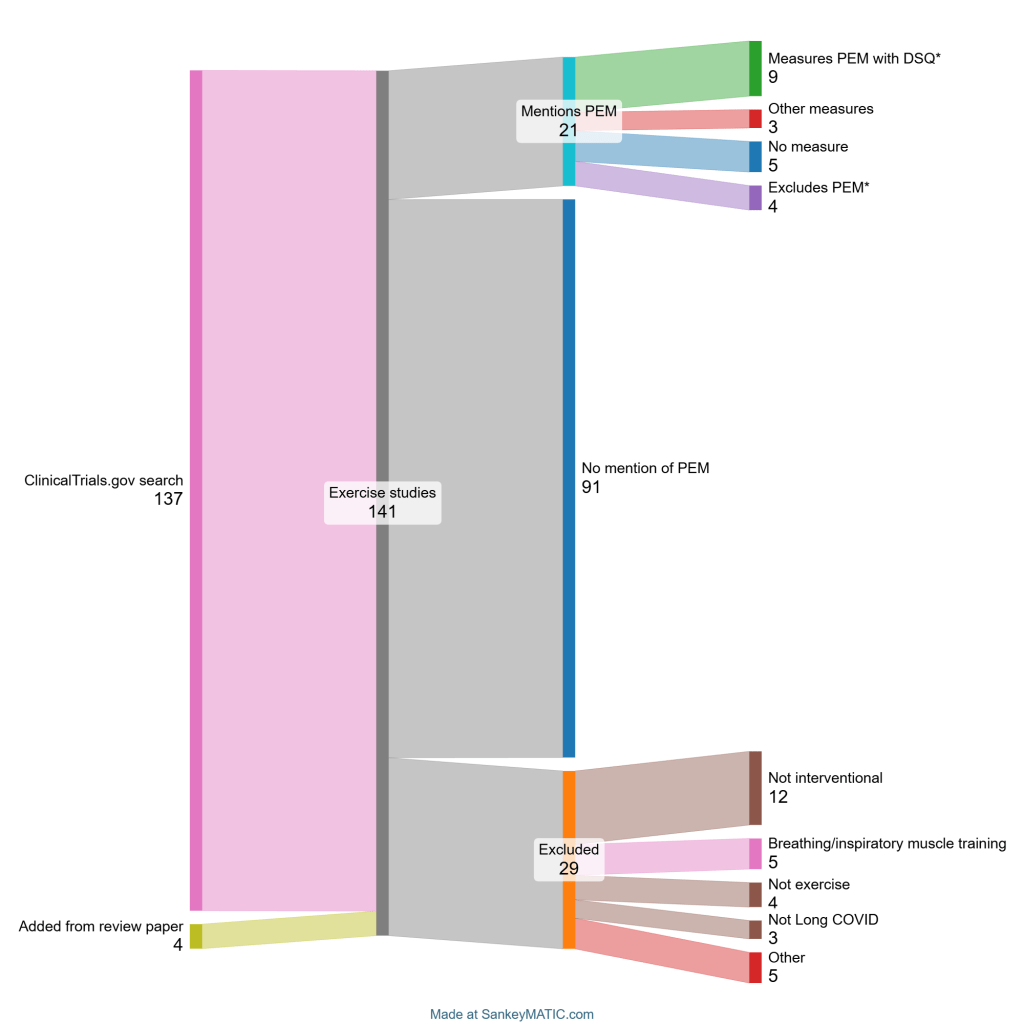

*Two of the trials that exclude participants with PEM still use it as an outcome measure since the researchers suspect some participants may experience PEM during the trial. Chart by Simon Spichak.

*Two of the trials that exclude participants with PEM still use it as an outcome measure since the researchers suspect some participants may experience PEM during the trial. Chart by Simon Spichak.

We reviewed exercise-related trials registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database up until November 17, 2025. Trials of hospitalized patients or those with an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection were excluded. Four trials were later added from research studies that looked at exercise in Long COVID.

The key findings:

Of 112 exercise-related trial registrations for Long COVID, only 21 mentioned PEM.

Only 14 trials assessed PEM, with 2 excluding participants with moderate to severe manifestations of it and another 2 excluding any participants with PEM.

While the number of trials registered each year has decreased since 2023, the share of trials mentioning PEM has increased.

Only half of studies completed by July 2024 have published their results.

Experts like Leonard Jason, a professor at DePaul University who developed the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ), which is used to screen for PEM, were surprised by the analysis. “I would think, as Long COVID often has as one of its symptoms PEM, that studies involving exercise or activity would make some efforts to measure this construct,” Jason told The Sick Times.

Omitting PEM entirely — not even mentioning it in the background alongside other Long COVID symptoms — reflects a basic lack of understanding of the disease. The studies that do measure PEM usually use the DSQ questionnaire. As an outcome measure, it might not capture PEM completely. For example, it doesn’t account for people reducing their activities to avoid PEM, and may not capture non-exercise triggers.

“People who are performing these studies are extraordinarily ignorant, and their ignorance is dangerous,” Seltzer said.

The rationale behind these studies, Seltzer contests, is “extraordinarily naive” as “it presumes that the patient had never heard of exercise until a doctor told them exercise exists.”

People who are performing these studies are extraordinarily ignorant, and their ignorance is dangerous.

Jaime Seltzer, #MEACtion

Exercise trials that exclude people with PEM

Two of the current exercise trials are excluding participants with moderate to severe forms of PEM — though concerns have been raised by participants about the ability for one of these trials to do so effectively.

That trial is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s $1 billion flagship research program, RECOVER. Titled RECOVER-ENERGIZE, this trial aims to recruit 300 people with Long COVID. After patient-advocates and researchers first learned about the trial, which initially planned to trial only exercise, in early 2023, they warned it would harm patients with PEM. In response to that extensive criticism, the investigators added a pacing arm and updated its inclusion and exclusion criteria so that only those with mild PEM could participate, to minimize the harm. Lucinda Bateman, an ME clinician at the Bateman Horne Center, was also added as an investigator.

At the 2025 RECOVER-Treating Long COVID meeting, the presenters failed to answer a question from a participant asking whether the exercise protocol qualified as graded exercise therapy.

In response to a follow-up question asked by The Sick Times, session moderator Laurie Gutmann, from Indiana University School of Medicine, said the study was important to continue despite the criticism it had received because researchers working on the trial “still felt” that it was “a valid question to answer” and “an important treatment” to evaluate.

G. Michael Felker, Duke professor of medicine and an investigator on this arm of RECOVER-ENERGIZE, declined to respond to questions about the scientific rationale for the study, whether any participants had dropped out due to PEM, or how the “cardiopulmonary rehabilitation” differed from graded exercise therapy.

This follows RECOVER’s poor track record of listening to patient input and declining to explain the rationale behind their decisions.

An anonymous RECOVER-ENERGIZE participant told The Sick Times that the research staff were being attentive to PEM in the form of exercise but may not have been measuring the impacts of cognitive and emotional exertion. They raised concerns that the trial could be used to promote graded exercise therapy, which has harmed many with Long COVID and ME.

Jason, who developed the DSQ questionnaires, said that he had spoken with the investigators when they were setting up the trial. “I do believe they are trying to screen out those with PEM,” he said, adding that it is “not an easy symptom” to identify and assess.

Over email, Bateman told The Sick Times that this arm of the trial is a few subjects away from reaching the enrollment goal. She also clarified that the trial is “personalized cardiopulmonary rehabilitation,” and “not exactly an exercise trial” aimed at people with “clinically significant PEM.” Still, it involves a one-on-one rehab program with a physiotherapist.

A smaller exercise study at UCSF

Matthew Durstenfeld, a cardiologist and assistant professor at the University of California, San Francisco, is running a 20-person pilot exercise trial that also excludes participants who self-report moderate or severe PEM from the trial. The screening procedure involves the DSQ and one-day cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET).

Originally, the study’s goal was to test whether an exercise treatment is feasible and tailor exercise recommendations for people with Long COVID who have chronotropic incompetence, which makes the heart unable to properly adapt to increased physical demands. In another pilot trial Durstenfeld’s team conducted, similar symptoms in people with HIV improved with exercise training.

However, this trial was expanded to include people with Long COVID who don’t have chronotropic incompetence because of recruitment challenges. Most of the participants in the trial don’t have PEM, though a few with mild PEM have enrolled. Durstenfeld doesn’t think it makes sense to run trials involving exercise that don’t take PEM into account.

Measuring PEM, he said, is important for making sure participants are safe and to help researchers understand the biological underpinnings of PEM. Especially for researchers conducting trials that could induce PEM, he told The Sick Times that researchers must have a “commitment to participant well-being” and develop the trust of participants that their study is being conducted in “good faith effort to really help people.”

“Exercise rehabilitation has a strong evidence base [for other chronic conditions], including post-COVID hospitalization and in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [POTS],” said Durstenfeld. “I think that there’s scientific equipoise about whether exercise is helpful, harmful, or neutral for people with Long COVID. Without measuring PEM and taking that into consideration, it’s hard to know.”

Exercise rehabilitation in HIV and POTS does not cure the disease and is offered as a supplemental rehabilitation.

Researchers must have a “commitment to participant well-being” and develop the trust of participants that their study is being conducted in “good faith effort to really help people.”

Matthew Durstenfeld, UCSF

Patients have raised serious concerns with allocating research funding and efforts toward exercise as an intervention, which has shown serious harms and failed to show any effect so far in Long COVID and ME, or provide much explanatory power in the context of the pathophysiological findings of the disease. If exercise has any effect on symptoms, for example, it won’t provide much insight as to whether or not viral persistence, autoimmunity, or immune dysregulation are playing any role in driving the disease or symptoms.

After Vrije University Amsterdam researcher Rob Wüst published work showing that exercise-induced PEM exacerbated muscle abnormalities in Long COVID, Durstenfeld and his team paused the study for a year to make sure it was still safe to continue. “We wanted to make sure we weren’t going to harm anyone,” he said. Ultimately, they decided to continue running the trial as is.

As of October 2025, none of the study participants have reported PEM. If that does happen, the researchers will have a risk-benefit conversation with the participant to help them decide whether to continue the study.

Since the study is a pilot trial and mostly excludes people with PEM, Durstenfeld emphasized that it will help researchers determine whether such an intervention is feasible and potentially helpful, to inform further trials.

But these two trials are outliers. The majority do not mention or measure PEM, or apparently take any steps to ensure participant safety. Even worse, since those trials are poorly designed, the information they provide is low quality.

“I imagine that some human suffering went into this, and that some of those people are sicker than before and may never return to their previous baseline,” said Seltzer.

Disclosing data, measuring PEM

U.S. law requires researchers and companies to disclose drug trial data within a year of a study’s completion — but this rule is frequently broken. Trials involving exercise don’t have the same legal requirement. In The Sick Times’ analysis, 25 of 50 studies whose completion date was set to July 2024 or earlier had published their data.

“It’s the right of the participant to know the findings of the trial,” Leticia Soares, a researcher at the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, told The Sick Times. “It takes a lot to participate in studies.”

While all the experts that The Sick Times spoke to agreed that measuring PEM is important, there is currently no perfect metric for doing so.

The DSQ survey developed by Jason is one of the most popular methods for assessing PEM. But it is intended to be used as a screening tool for PEM rather than a diagnostic, and without confirmation from a healthcare practitioner, it leads to a lot of false positives.

A two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test may be used, but it is costly for researchers and may be dangerous or inaccessible for patients with moderate to severe PEM. A simpler approach involves asking participants throughout the study if they’re experiencing PEM and how severe it is.

Many exercise trials also overlook what happens to the patient after a study visit. A six-minute walk test might show slight improvement in the research setting, Seltzer said, but when the participants go home, they crash. Because this later outcome isn’t tracked, trials aren’t well equipped to measure the harms.

PEM can also develop later in the disease. Some patients might start to develop it as a symptom as the study progresses. And the PEM could last for weeks — a Cornell study of people with ME found that some patients took weeks to recover from a two-day CPET test. Seltzer recommends that researchers follow patients for up to a month after the study ends.

Research studies that exclude people with moderate and severe ME might be missing a piece of the puzzle, according to some patients. Peter Neehus, a person with ME and Long COVID who participated in one of Rob Wüst’s MuscleME studies, told The Sick Times that researchers “must seriously look for an alternative research method so that even very seriously ill patients can be studied.”

Researchers “must seriously look for an alternative research method so that even very seriously ill patients can be studied.”

Peter Neehus, study participant with ME and Long COVID

Simon Spichak is a Toronto-based science and health writer with a MSc in neuroscience. His work has been published in Being Patient, The Guardian’s Scientific Observer, The New York Times, The Daily Beast, Proto.Life, and other outlets. He is the founder of a low-cost online therapy clinic for students called Resolvve and runs a newsletter about underreported health and disability issues in Canada.

Simon will continue to report on the pervasiveness of exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in Long COVID and ME spaces as a contributing writer at The Sick Times. To send him secure tips, reach out on Signal at simonspichak.64.

All articles by The Sick Times are available for other outlets to republish free of charge. We request that you credit us and link back to our website.

The Sick Times is dedicated to independent Long COVID journalism, without denial, minimizing, or gaslighting.

Support us during our end-of-year fundraiser, and you’ll help us continue this work into 2026. From November 1 to December 31, donations will be matched up to $1,000 per person by NewsMatch; learn more about the fundraiser here.

By donating to this non-profit publication, you:

Help us produce more unique news and commentary stories like this one.

Support free news access for everyone impacted by Long COVID, regardless of their financial situation.

Keep this crisis in the spotlight, even as the government tries to erase Long COVID.

Make a monthly tax-deductible donation:

Not ready to give monthly? A one-time donation of any amount also has a profound impact.

Related storiesLike this:

Like Loading…