Palaeogenomic dataset

DNA extracts were obtained from teeth (n = 10) and petrous bones (n = 13) and converted into multiple single-stranded non-uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UDG) treated libraries. All samples were sequenced after enriching for approximately 1,240,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). For high-quality low-coverage samples reporting between 100,000 and 300,000 SNPs (GMO001, GMO009, GMO010, and GMO012), a second round of enrichment was performed on partial-UDG-treated libraries using the Twist capture protocol25 to increase SNP coverage and ensure robust performance in population genetic analyses. Palaeogenomic data were successfully generated for 14 individuals (see Table 1 and Supplementary Data 2). Nine ultra-low coverage samples (between 1000 and 10,000 SNPs) were only evaluated for sex and kinship relationships. Among the high-quality genomes (>100,000 SNPs), two were directly radiocarbon dated specifically for this study (GMO005 and GMO007), extending to 12 the number of direct dates available for the entire site (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 1). Average fragment length and median rate of cytosine-to-thymine damage at the terminal nucleotides of the reads were consistent with the age of all samples, and no patterns of contamination were found at the nuclear or mitochondrial level for samples that passed the threshold for quality, except the male individual GMO009, for which we estimated 12% contamination on the X-chromosome (Supplementary Data 3–5). After retaining only post-mortem damaged (PMD) reads, we performed comparative principal component analysis (PCA) and excluded further contamination for the filtered sample GMO009, which was incorporated in subsequent steps (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3). For PCA, samples with less than 20,000 SNPs were filtered, whereas for subsequent population genetic analysis, individuals that were genetically related or of low coverage (<100,000 SNPs covered) were excluded.

Table 1 Summary statistics for the palaeogenomic dataset from Grotta della MonacaCommunity structure and parent-offspring union

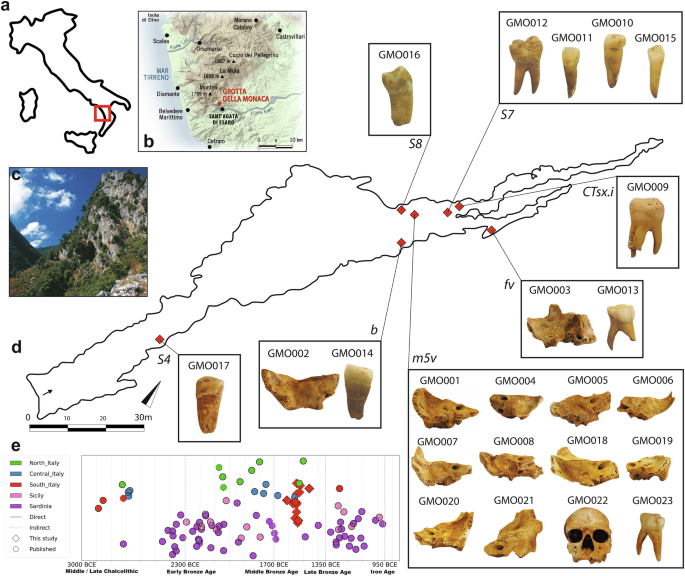

We combined genomic data and archaeological information to investigate the spatial organization of the burial ground. Based on pairwise mismatch rate calculation, three samples originate from the same individual (Methods, Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 6). Hence, we merged these data into a single genetic profile, GMO006, yielding more than 690,000 SNPs. Genetic sexing identified ten females and eight males among the sparse skeletal material in the cavity. Due to low coverage, we could not reconstruct genetic sex for individuals GMO014 and GMO016, and attribution for individual GMO017 was considered unreliable. Notably, except for one adult male (GMO022), all individuals from burial area m5v (n = 10) were either adult females or juvenile-to-infant subjects. The analysis of uniparentally inherited markers displays a heterogeneous picture for the funerary ground (Supplementary Data 7, 8). Among the 13 individuals with sufficient coverage for assigning haplogroups, we identified 12 distinct mitochondrial haplotypes, with only the adult male GMO022 and the infant male GMO015 sharing identical haplotypes from the mitochondrial haplogroup H1e (private mutations A6779G, T16127C, T16224C and T16519C). In contrast, the Y-chromosome haplotypes were slightly more homogenous, with four different haplogroups reconstructed from the six male individuals analysed. Two of these (GMO009 and GMO015) belong to a sub-branch of haplogroup R1b, with private mutations leading to the R1b1b and R1b1a1b haplotypes, respectively, while individuals GMO007 and GMO022 share the H2~ Y-chromosome lineage (Supplementary Note 3).

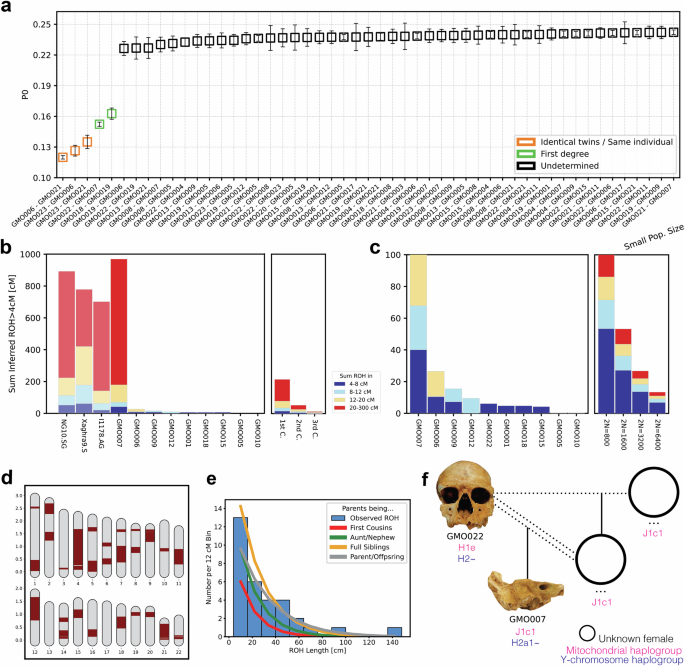

Fig. 2: Genetic relatedness, inbreeding and pedigree reconstruction in the community from Grotta della Monaca.

a Pairwise mismatch rate values among 20 individuals with at least 1000 SNPs. Each point represents a unique pairwise comparison between two individuals, and error bars indicate the standard error of the mean PMR across all overlapping SNPs for that pair; b Sum of runs of homozygosity (ROH) segments >4 cM calculated from the Grotta della Monaca community and a set of the most inbred individuals found in the literature. Colours separate ROH length classes in 4–8 cM (blue), 8–12 cM (sky blue), 12-20 cM (yellow) and >20 cM (red); expectations for close-kin unions is displayed on the right; c diffuse patterns of shorter ROH segments between the individuals from Grotta della Monaca, evidence of background relatedness. Expected ROH for small populations is shown on the right; d fractions of ROH segments in autosomal chromosomes and e histogram of >12 cM ROH length distribution for the extremely inbred individual GMO007; f the unusual pedigree reconstructed for individuals GMO022 and GMO007. Dotted lines denote reproductive union, while da ouble dotted line represents a consanguineous union. All published data are taken from the AADR repository v62, freely available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/reich_lab.

Analysis of genetic relationships within the burial site identified two cases of first-degree relatives (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Data 9, 10). Using KIN26 we classified these relationships as parent-offspring pairs: intriguingly, both GMO007-GMO022 and GMO018-GMO019 originate from burial area m5v. Based on the estimated age at death of the skeletal remains, the adult GMO022 was determined to be the father of GMO007, a pre-adolescent male. In the case of the two female individuals GMO018 (likely 30+ years at death) and GMO019 (possibly 20+ years at death), the commingled nature of the skeletal remains and the absence of a shared relative prevented us from distinguishing which one was the mother and which the daughter. We assessed potential distant relationship ties using identity-by-descent (IBD) segments inferred by ancIBD27 on individuals with over 600,000 genotyped SNPs. The majority of the individuals did not exhibit evidence of distant genetic relatedness, except for one case: the adult female individual GMO005 and the juvenile male GMO006, both found in burial sector m5v, shared 10 long IBD segments ( > 12 cM), indicative of a fourth-degree relationship (Supplementary Data 11).

To test the possibility of inbreeding events within the community of Grotta della Monaca, we measured runs of homozygosity (ROH) segments in 10 individuals with sufficient genomic coverage (>400,000 SNPs) using hapROH28 (Fig. 2b). Briefly, an abundance of ROH segments >20 centimorgans (cM) long corresponds to consanguineous mating of an individual’s parents, while an increased number of short runs indicates distant parental relatedness, which is commonly observed in small or isolated populations. Only two of the analysed individuals (GMO006 and GMO009) carried several short ROH longer than 4 cM (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Data 12), summing up to a total ROH length of 26 cM and 18 cM, respectively. These results indicate that the parents of the two individuals were distantly related, possibly pointing to the last 6–10 generations. Additionally, four individuals exhibit few short ROH, no longer than 5 cM, suggesting a diffused pattern of remote inbreeding in the community. Based on the inferred ROH, we estimated the effective population size (Ne) of our samples and compared it to a subset of relevant Bronze Age populations taken from the literature. Our estimates from the community of Grotta della Monaca corresponded to close to 5000 reproducing individuals (Ne = 4698, 2610–9778 95% CI, Supplementary Data 13), similar to the population size calculated from MBA communities in Iberia (Ne = 3167, 1470–8814 95% CI) and Croatia (Ne = 3018, 1564–7016 95% CI), but remarkably smaller than of groups from the coeval Tumulus culture in Central Europe (Ne=10624, 3441-50000 95% CI), or the large Middle to Late Bronze Age urban centre of Alalakh in Northern Levant (Ne = 79537, 18,123–50,0000 95% CI). Notably, individual GMO007 exhibits the highest sum of long ROH segments ever reported in ancient genomic datasets to date (Fig. 2b). Nearly 800 cM of his genome consists of ROH segments longer than 20 cM, with the longest stretch extending 142 cM. Such segments were distributed across large fractions of the autosomal chromosomes (Figs. 2d and e), providing indisputable evidence that the young male was the offspring of a first-degree incestuous union. This result stands as an exceptionally rare and remarkable finding, the earliest identified in the archaeological record, with only three comparable instances among ancient populations to date. One extremely inbred individual has been reported in Middle Neolithic Ireland29 (NG10.SG), radiocarbon dated to 3339–3028 cal. BCE, which showed nearly 670 cM of >20 cM ROH segments, the longest reaching 65 cM. Another individual from Chalcolithic Israel30 (I1178.AG), archaeologically dated to 4500–3500 BCE, reported 560 cM of ROH longer than 20 cM and the longest stretch reaching 91 cM. A third individual from Late Neolithic Malta31 (Xaghra9.SG), radiocarbon dated to 2530-2400 cal. BCE, exhibited a total of approximately 360 cM of >20 cM ROH segments, including one stretch measuring 111 cM (Supplementary Data 12).

Through kinship analysis, we identified the father of GMO007 being GMO022, but not the mother. Leveraging uniparentally inherited genetic markers, we find that the two individuals do not share a matrilineal connection. This genetic evidence unambiguously reveals that GMO007 was the son of GMO022 and his daughter (Fig. 2f).

The genomic makeup of the Middle Bronze Age community from Grotta della Monaca

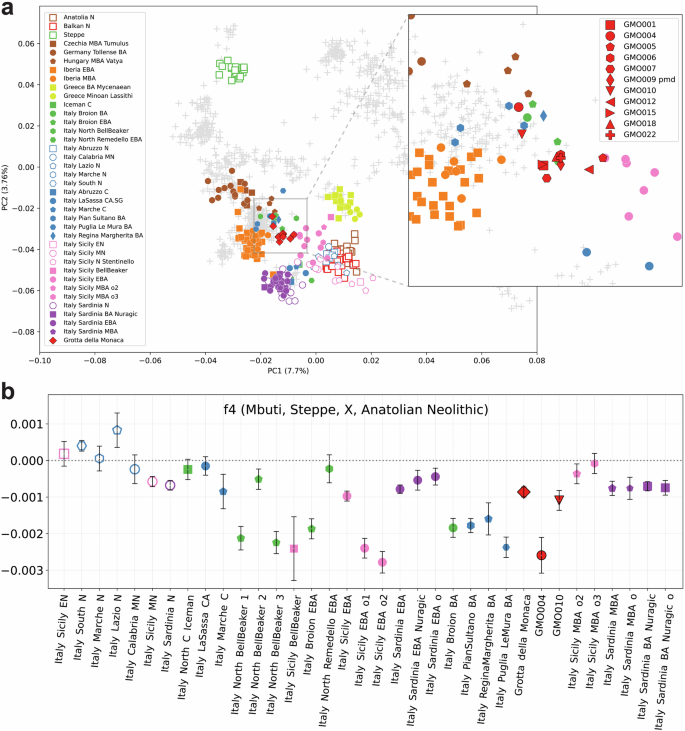

We explored the biogeographical origin and ancestral structure of the MBA community from Grotta della Monaca by performing a principal component analysis, projecting the newly generated and relevant published ancient DNA data onto the genetic variation calculated from 1074 present-day western Eurasians (Supplementary Data 14). Most of the individuals from Grotta della Monaca form a distinct, relatively homogeneous cluster located in the PCA space between Bronze Age Central Europeans, Early (EBA) and MBA Iberians, and Bronze Age (BA) Sicilians (Fig. 3a). We observe the closest genetic similarity to published data from the Italian peninsula, specifically to EBA and MBA individuals from the Northeast (Italy Broion EBA/MBA) and Sicily (Italy Sicily EBA), suggesting a high degree of genetic continuity within these regions during this period. A modest shift towards coeval populations from Central Europe is visible for two individuals (GMO004 and GMO010), suggesting an increased genetic affinity with individuals from EBA and MBA North-Central Italy (Italy North Bell Beaker and Italy Pian Sultano BA) and Hungary (Hungary MBA Vatya). Moreover, two individuals (GMO005 and GMO012) exhibit a slight shift towards Early Bronze Age Sicilians; however, formal statistical tests do not indicate significant genetic heterogeneity between these individuals and the main cluster (Supplementary Data 15).

Fig. 3: Population structure and Steppe-related ancestry in Bronze Age Italians.

a Principal component analysis calculated on a set of present-day western Eurasians (n = 1074) from the Human Origin Affymetrix dataset. Projected ancient individuals (n = 278) are displayed as coloured shapes; the zoom in shows GMO individuals (red) forming two separate clusters; b genetic variation in Steppe-related ancestry among Italian individuals from the Neolithic to the Middle Bronze Age assessed using f₄-statistics. Each point represents one f₄-statistic per population; error bars indicate the standard error of each statistic, calculated as f₄ divided by the corresponding Z-score. Populations are ordered chronologically from left to right. Symbol shapes correspond to population groupings as shown in the legend of Fig. 3a. All published data are taken from the AADR repository v62, freely available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/reich_lab.

The genetic attraction towards Bronze Age Central Europeans observed in some of our individuals may reflect different proportions of ancestry associated with Western Steppe pastoralists, who made a large contribution in shaping the genomic make-up of Bronze Age Eurasian populations. To determine whether the patterns observed in PCA reflect genuine differences in genetic ancestry, we assessed pairwise cladality between individuals using qpWave32,33. While cladality could not be rejected between individuals from Grotta della Monaca and Early Bronze Age Sicilians, a single individual, GMO010, showed signals of rejection of the proposed model at p < 0.01 when compared to almost all other individuals from the same community (p-values ranging 1.29e–06 to 0.0126, Supplementary Note 5, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 16). This outlier reported affinity only with individual GMO004 (p = 0.281), matching the observed clustering in the PCA, and exhibited increased attraction to Early and Middle Bronze Age groups from Northern Italy. We classified individuals GMO004 and GMO010 as genetic outliers for further group-based analyses, but marked results for individual GMO004 as statistically underpowered due to low coverage (<100,000 SNPs).

We then assessed variation in Steppe-related ancestry among prehistoric individuals from Italy – including the newly reported GMO group – by running f-statistics in the form ƒ4(Mbuti, Steppe; X, Anatolia N), where X represents prehistoric Italian individuals. The Steppe and Anatolia N groups served as proxies for the BA Western Steppe pastoralists and the Early Neolithic Farmers from Anatolia, respectively. Consistent with previous findings, published EBA and MBA individuals from Northern, Central, and Southern Italy exhibit affinity to Steppe-derived ancestry (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Data 17). This result is in line with existing evidence for the presence of this genetic component in prehistoric Italian populations by at least 2300 BCE in the mainland34 and by 2400 BCE in Sicily33. Here, this pattern is also clearly visible in the Grotta della Monaca cluster (f4 = −0.0008, Z = −6.332), and extremely evident for GMO004 (f4 = −0.0025, Z = −5,307), while no remarkable differences are present for GMO010 (f4 = −0.0011, Z = -4.035).

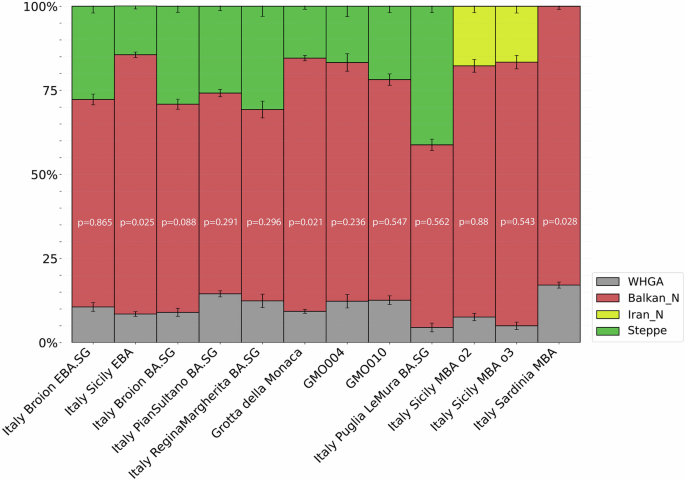

Subsequently, we modelled the genomic makeup of individuals from Grotta della Monaca as a combination of three ancestral proxies representing the three major contributors to European populations from the 3rd millennium BCE to the present day35, i.e., Western hunter-gatherers (WHG), the early European farmers (EEF), and the aforementioned western Steppe herders (Supplementary Data 18). We first tested the samples individually to support our clustering results (Supplementary Data 19). Then, using a distal approach for admixture modelling36 (Supplementary Note 6), we estimated that the GMO group derives 75.3% ± 0.8% of EEF ancestry when using Balkan N as source of EEF ancestry, 15.4% ± 0.9% ancestry from the Steppe, and 9.3% ± 0.6% from a subset of late Epigravettian and Mesolithic Hunter-Gatherers from Western Europe (WHGA) (Fig. 4). We estimated analogous proportions of hunter-gatherer ancestry in previously reported Italian Bronze Age groups, including Italy Broion BA (9% ± 1.2%), Italy North Bell Beaker 3 (9.4% ± 1.4%) and Italy Sicily EBA (8.5% ± 0.7%). Notably, the observed proportions of EEF and Steppe-related ancestries of the GMO cluster closely align with those of Early Bronze Age Sicilians (77.1% ± 0.8% and 14.5% ± 0.9%, respectively). The proportion of Steppe ancestry marks the most evident difference between the GMO cluster and the outlier GMO010. The latter exhibits, compared to the main genetic cluster, a higher affinity with Steppe populations (21.8% ± 1.9% Steppe-derived ancestry), a slightly greater proportion of hunter-gatherer ancestry (12.6% ± 1.3%), and a lower proportion of Neolithic farmer ancestry (65.6% ± 1.7%) (Supplementary Data 20). These patterns reinforce the PCA results of this individual and are shared with the second outlier GMO004, which however, we caution was slightly below the suggested cutoff for admixture modelling (~80,000 SNPs).

Fig. 4: qpAdm ancestry modelling of Grotta della Monaca individuals and coeval Italian populations.

Each bar represents the ancestry proportions inferred from a single qpAdm model for a population, using a three-way distal approach. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the ancestry coefficients as estimated by qpAdm. All published data are taken from the AADR repository v62, freely available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/reich_lab.

Motivated by previous evidence of Eastern-like ancestry in MBA Sicily33, we tested whether the Grotta della Monaca population carried genetic contributions from sources such as Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers (CHG) or Neolithic Iranian farmers, which have been used as proxies for Levantine-related ancestry. However, our qpAdm models did not provide a statistically feasible fit for either the GMO cluster or the genetic outlier GMO010. Similarly, we tested for North African ancestry, previously reported in Bronze Age and Punic-period samples from Sardinia33,37, but found no evidence of such genetic contributions in the Grotta della Monaca individuals.

To further explore possible sources of local ancestry, we tested several scenarios employing a proximal modelling approach (Supplementary Data 21). We leveraged the limited data available for Neolithic individuals from the Italian peninsula and surrounding islands to assess local farmer ancestry. Additionally, we incorporated Early Bronze Age individuals from either Northern Italy or Sicily to trace for a local origin of Steppe ancestry components. Regarding the outlier GMO010, models requiring the Grotta della Monaca cluster as a single source of ancestry did not fit its genomic composition. Instead, its ancestry was best explained by a model deriving the entire ancestry from the Early Bronze Age northeastern Italian group of Broion (p = 0.26), which confirms genetic affinities observed in previous results. Conversely, no-single source models successfully explained the genetic makeup of the main GMO cluster. In fact, robust two-way models required – alongside northern Italian EBA ancestry – a Neolithic or Middle Neolithic contribution ranging 30.2% ± 3.7% to 46.8% ± 4.9%, sourced from individuals in Central Italy (Italy Lazio N, p = 0.37), Southern Italy (Italy Calabria MN, p = 0.03) or Sicily (Italy Sicily MN, p = 0.11 and Italy Sicily Stentinello, p = 0.06).

Finally, we examined a panel of SNPs associated with functional and phenotypic traits (Supplementary Data 22). First, we explored 41 informative SNPs from the HirisPlex-S DNA test system38, and found alleles for blue eyes in six out of nine individuals with sufficient genomic coverage (Supplementary Data 23). Hair colour analysis revealed that almost all the individuals exhibited dark hair, either brown (n = 5) or red (n = 6). Additionally, the majority of the individuals reported general darker skin pigmentation, except for individuals GMO001 (p = 0.98, AUC loss = 0.001), GMO015 (p = 0.92, AUC loss = 0.05), GMO018 (p = 0.45–0.49, AUC loss = 0.02), and GMO022 (p = 0.55, AUC loss=0.04) who carried alleles linked to pale skin. Individuals GMO018 and GMO022 also carried genetic variants associated with lighter hair coloration (p = 0.86 and p = 0.89, AUC loss = 0.002 and 0, respectively).

We also explored functional SNPs annotated in the SNPedia and dbSNP datasets. We found that all individuals with sufficient genomic coverage carried ancestral alleles at SNPs associated with lactase persistence, suggesting that they might have suffered from lactose intolerance in adulthood. Given the observed inbreeding events within the population, we investigated SNPs associated with rare diseases to assess potential health implications. However, no notable genetic markers associated with inherited diseases were identified. One exception is the female individual GMO012, who carried the derived allele on the SNP rs8063 located on the gene UBE2I. This variant has been significantly associated with mild cognitive impairment in women, even though its phenotypic impact in this individual remains uncertain.