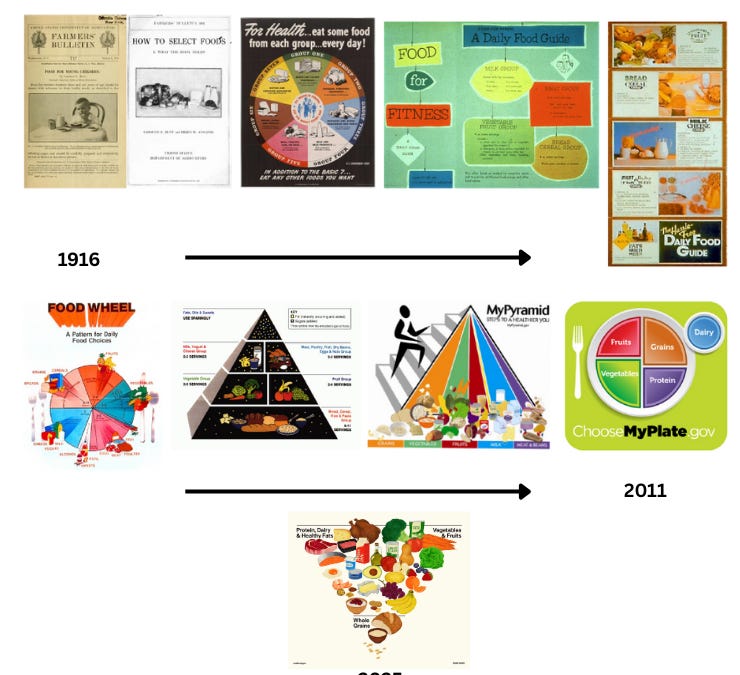

Federal nutrition advice has evolved over the years. We’ve gone from the food pyramid to MyPlate, and now to a new inverted pyramid. Every five years, the government releases updated guidance, often with new priorities and messaging.

On January 7, USDA and HHS released the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).

There was more attention to this update than usual, which is a good thing. But many of you had lingering questions about what actually changed and why it matters. So I asked Megan Maisano, registered dietitian nutritionist and YLE’s nutrition contributor, to help break it down and answer your specific questions.

The DGA is the nation’s nutrition policy guide. Its main job is to guide federal decisions about food and nutrition to promote health and prevent disease, including:

Federal nutrition standards (e.g., what to include in school meals, military dining facilities)

Nutrition education programs (e.g., what to teach about)

Clinical practice tools and dietary assessment resources (e.g., how clinicians can better meet the needs of patients and how to assess diet quality)

Some programs are required to follow the DGA, while others use it as best-practice guidance. As a registered dietitian, I often use it as a trusted, up-to-date resource.

Traditionally, the DGA follows a two-step, five-year process:

An independent expert committee reviews the science and publishes a Scientific Report.

USDA and HHS use that report to write the final guidelines.

This framework is designed to promote scientific rigor, transparency, and public trust. The timeline below shows the planned process for the 2025-2030 DGA.

But this isn’t exactly what happened this year.

Three main things:

1. The scientific process shifted. Instead of relying on the expert Scientific Report, the final DGA was based on a separate Scientific Foundation created quickly and privately by contracted scientists in 2025. This change has raised concerns among researchers about scientific rigor, transparency, and the influence of predetermined priorities on federal nutrition guidance.

Process matters because it shapes what evidence is considered, how it is evaluated, and whose expertise informs decisions. A rushed timeline and an opaque process rewrite the playbook, raising concerns about trust, continuity, and the stability of future guidelines as priorities and ideologies change.

2. Health equity was removed. The new Scientific Foundation criticized the earlier report for focusing too much on health equity and removed it from consideration.

Health equity matters because income, culture, access to food, and representation in research strongly affect diet and health. Ignoring these factors raises questions about how well the guidelines apply across different communities and real-world conditions.

3. The tone became more political. The messaging took a sharp turn toward greater persuasiveness, even becoming propagandistic. During the DGA press conference, past guidance was called “faulty” and “based on dogma,” and it was suggested that “our government has been lying to us.”

This framing blurs the line between science and politics and risks further eroding trust in public health institutions. It also makes the recommendations harder for health professionals to reference and apply.

Less than you may think, but the details matter.

The DGA still emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, protein foods, and dairy, while limiting added sugar, saturated fat, sodium, and alcohol. But there are several notable shifts.

1. “Real Food” takes center stage. The guidelines stress eating “real” foods and limiting highly processed foods. While reducing ultra-processed foods can be beneficial, the term “highly processed” is not clearly defined. This messaging has even extended beyond the DGA, appearing in a Super Bowl ad with the slogan: “Processed Food Kills.”

Why does this matter? Because 48 million Americans face food insecurity, including 1 in 5 children. Emphasizing “real food” risks stigmatizing and disempowering people who rely on processed foods for accessibility, affordability, or convenience.

Also, not all processed foods are the same, and many can support a healthy diet. Processing can improve safety, shelf life, and nutrient delivery in cost-effective ways. Recommending “real food” and shaming processed foods without nuance oversimplifies a complex food system and risks alienating the very communities that federal food programs aim to support.

2. More emphasis on protein. Protein recommendations increased, with animal-based sources more prominently emphasized in the pyramid. Protein is important for satiety (feeling full), growth, muscle health, and aging, so this change isn’t inherently bad, though more balance with plant-based options could support flexible eating patterns. It’s also uncommon for DGA to change daily requirements.

Why does this matter? Most Americans already meet protein needs, while only about 6% meet recommendations for fiber, a nutrient strongly linked to multiple health outcomes. The shift raises questions about priorities.

3. A new framing of saturated fats. Foods high in saturated fat, like red meat, butter, and full-fat dairy, are now framed as sources of “healthy fats,” alongside nuts, oils, and seafood.

Why does this matter? There is evidence suggesting saturated fat affects health differently depending on food source and processing, but nuance can be lost in broad encouragement. The recommended limit for saturated fat remains at less than 10% of calories, which many Americans already exceed. With heart disease still the leading cause of death, some worry this shift may confuse the public.

4. Stricter limits on added sugar. The new guidance recommends avoiding added sugar entirely until age 10 then limiting it to less than 10 grams per meal, compared to the previous limit of less than 10% of calories after age two.

Why does this matter? Strong guidance is reasonable. It is important to limit added sugar in children’s diets, particularly in early childhood when taste preferences are established. Still, greater contextual flexibility and clearer distinctions between sources of added sugar and the role of otherwise nutrient-dense foods with small amounts (e.g., lightly sweetened oatmeal or yogurt versus soda or desserts) would have been helpful for families navigating real-life eating.

Completely avoiding added sugar until age 10 is unrealistic for many families and could encourage overly rigid relationships with food.

5. A new graphic. The DGA replaces MyPlate with an inverted food pyramid. Protein, dairy, fats, vegetables, and fruit appear at the top, while whole grains are emphasized less.

Why does this matter? While the hierarchy is clear, the graphic lacks guidance on portion sizes or balance, a key strength of MyPlate that helped people apply recommendations in daily life.

Most individuals won’t notice much difference. But federally funded programs will.

Why does this matter? School meals, WIC food packages, and military dining must align with the DGA. Implementing stronger “real food” messaging and stricter sugar limits will require more funding, staff training, and kitchen capacity, all in systems that are already stretched thin.

For individuals, the basic and boring foundations of health don’t change much over time: nutrient-dense diets, increased physical activity, and limited substance use.

The 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines keep many familiar recommendations but introduce meaningful shifts, especially in the development process and messaging.

Moving away from a transparent, independent scientific review and toward more values-driven language raises concerns about credibility and trust. That matters because the DGA shapes nutrition policy, education, and Americans’ understanding of healthy eating.

In public health nutrition, how guidance is developed can matter just as much as what it says.

Love, Megan

PS. A lot of you had more specific questions, so rather than turning this into a long post, I’m answering them in the comments. Come join the discussion…I’ll be there!

P.S.S I’m always learning and often draw upon the work of other experts to reflect, challenge, and sharpen my thinking. If you’re interested in more detailed perspectives on the new DGA, I recommend checking out the thoughts from Kevin Klatt, Jessica Knurick, and Dariush Mozaffarian.

Megan Maisano, MS, RDN, is a registered dietitian nutritionist. During the day, Megan works at National Dairy Council, a non-profit dairy nutrition research and education organization. (She does not write about the dairy industry for YLE.) Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. YLE reaches more than 425,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade below: