Credit: ChrisChrisW/Getty Images

Credit: ChrisChrisW/Getty Images

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen have discovered two proteins produced by gut bacteria that could offer a new therapeutic target to treat a wide range of metabolic diseases, including obesity and diabetes. In a study published in Nature Microbiology, these proteins were shown to help regulate blood sugar, reduce weight gain, and increase bone density in animal models.

“This is the first time we’ve mapped gut bacteria that alter our hormonal balance,” said Yong Fan, PhD, assistant professor at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen and first author of the study.

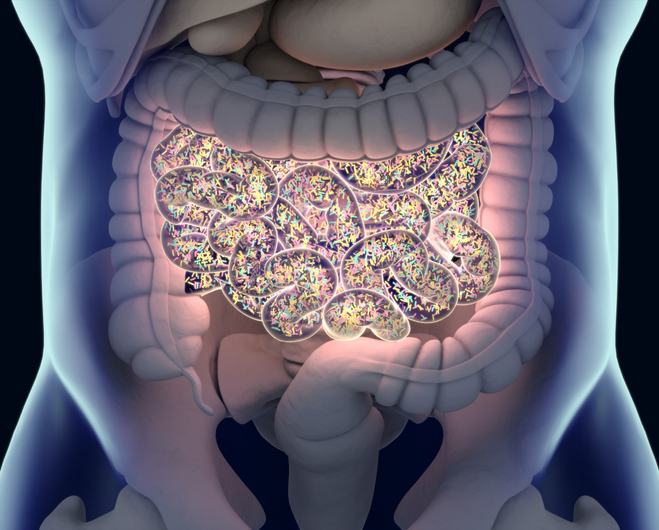

Despite the growing body of research showing the extent to which the microorganisms living in our gut can affect our health, the gut microbiome remains a largely untapped resource for the discovery of novel compounds that can regulate human physiology.

Using a public database, Fan and colleagues performed a genomic analysis to identify promising candidates by looking for protein sequences in prokaryotes that hold similarities to human proteins involved in metabolism. This led them to find two polypeptides, called RORDEP1 and RORDEP2, that share 24% and 25% sequence identity with the human hormone irisin.

Both peptides are naturally produced by specific strains of a bacteria commonly found in the gut known as Ruminococcus torques, whose role in metabolic regulation had so far remained unexplored. An analysis of 1,492 intestinal metagenomes confirmed the presence of R. torques in 93% of individuals with an average relative abundance of one percent, with high variability found between individuals.

“We found that the number of RORDEP-producing bacteria can vary by up to 100,000 times between individuals, and that people with high levels of these bacteria tend to be leaner,” said Fan. “In experiments with rats and mice that received either RORDEP-producing gut bacteria or the RORDEP proteins themselves, we observed reduced weight gain and lower blood sugar levels, along with increased bone density.”

These effects were accompanied by the upregulation of genes involved in burning fat and generating heat, while genes involved in synthesizing fat were downregulated. RORDEP1 was found to induce a rise in the plasma levels of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1), peptide YY (PYY) and insulin, three hormones that regulate appetite and blood sugar levels. The peptide also suppressed the gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) hormone, which is linked to weight gain.

Fan is the COO and co-founder of GutCRINE Pharmabiotics, a spinout of the University of Copenhagen that has undertaken the clinical development of novel therapeutics based on the discovery of RORDEP peptides. “We’re now translating our basic research into human studies to explore whether RORDEP-producing bacteria or the RORDEP proteins—either in their natural or chemically modified form—can serve as the foundation for a new class of biological drugs known as pharmabiotics,” said Oluf Pedersen, MD, DMSCi, professor at the University of Copenhagen, CSO and co-founder of GutCRINE, and senior author of the study.

“Looking 10 to 15 years ahead, our goal is to test the potential of RORDEP-producing bacteria for both prevention and treatment. We want to investigate whether they can function as a second-generation probiotic—used as a dietary supplement to prevent common chronic diseases—and whether RORDEP-proteins in modified forms can be developed into future medicines for cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and osteoporosis.”