Better get used to it. Maybe for a long time.

As a new wave of U.S. tariffs on regions and countries, including Europe and South Korea, took effect on Thursday, business executives in the United States are no longer holding out hope that the Trump administration’s global trade regime will change any time soon.

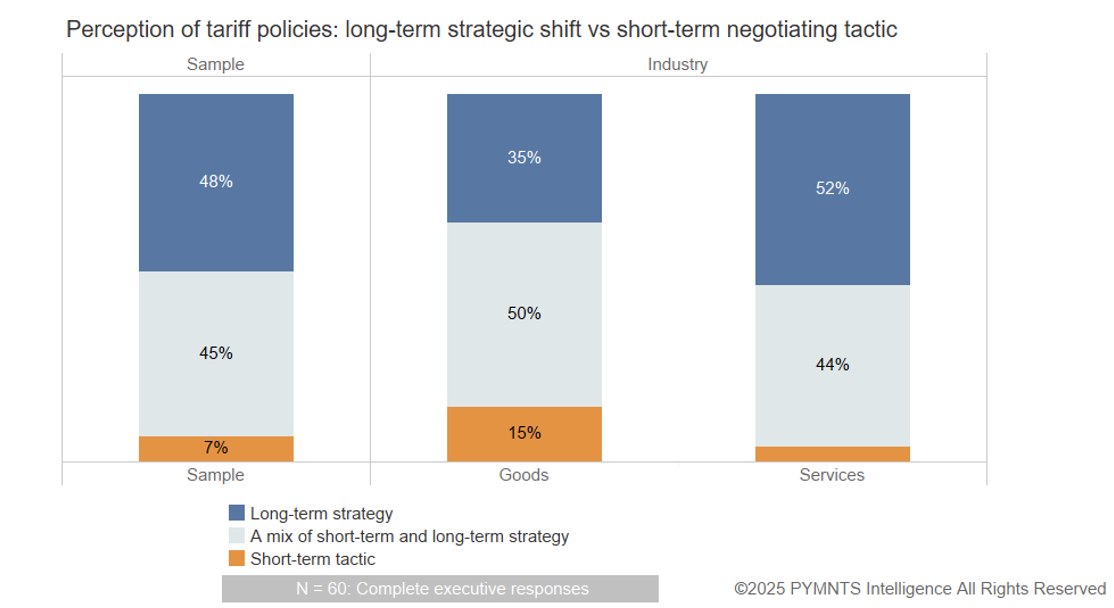

New data from a forthcoming PYMNTS Intelligence study shows that more than one in two senior product executives at U.S. firms with up to $1 billion in annual revenues regard the levies as a long-term shift by the U.S. government. Nearly half view the “reciprocal” duties as embodying a strategic policy shift that is part long-term, part short-term. Only 7% regard tariffs as a flash-in-the-plan negotiating tactic that will pass. For the majority of middle-market companies, higher costs for imports are now baked into their mindsets — and, likely, their future operations.

Corporate product leaders oversee the entire lifecycle of a product, whether it’s tangible things like shoes and sofas or intangible goods like software and financial apps. From strategy, budgeting and planning to production and measuring success, these executives have to analyze the competition, forecast consumer demand, secure imports of raw materials, components and goods — all often months, if not longer, in advance. What they think now determines what they’ll be doing down the road, impacting the economy and consumer spending trends.

PYMNTS Intelligence surveyed 60 heads of product at middle-market companies from July 21 t0 July 30. One question asked: “To what extent do you believe recent tariff policies are part of a long-term strategic shift in U.S. economic policy versus a short-term negotiation tactic?” Trump, long a proponent of tariffs, views the levies as a way to reduce America’s trade deficit — the shortfall between what America buys from abroad and what it sells abroad — and “correct longstanding imbalances in international trade and ensure fairness across the board.”

It’s true that the U.S. offers some foreign countries better trade terms than they give the U.S. But that’s often a reflection of a particular country’s strength, or comparative advantage, in making a given product, a fact first described by influential economist David Ricardo in 1807. Think Switzerland for watches and France for wine. The average U.S. tariff rate of 22.5% is the highest since 1909, according to The Budget Lab at Yale.

Strikingly, goods firms — the industry with the most to lose from levies on imports from countries including China and Vietnam, which now bear tariffs of 55% and 20%, respectively — are the least likely to view the duties as a long-term policy shift. Just over one in three see them that way. They’re also the most likely, at 15%, to view them as short-term negotiating tactic by Trump, who approaches trade agendas as deals to be sealed. The rest, or one in two, see the new tariff era as having both long-term and short-term components.

By contrast, services firms, which are indirectly impacted by tariffs because they tend not to import goods but work for companies that do, are more likely to expect tariffs to stay. More than half, or 52%, see the new tariff policy as lasting, while only 4% regard them as a short-term tactic. Some 44% are in the camp of both long term and short term.

The mixed camp that regards tariffs as both long-term strategic and short-term tactical may reflect the constantly changing nature of Trump’s tariffs agenda, with a carousel of stop-and-go negotiations and threats to levy, pause, raise or lower duties on individual countries. On Wednesday (Aug. 6), the president threatened a 100% duty on imported semiconductors, a crucial component of electronics in smart phones, computers and cars, unless their foreign manufacturers build plants in the United States or promise to do so.

Broader Impact

Tariffs could prompt goods companies to make so-called “dynamic pricing” — when that can of soda costs more on a hot day — more prevalent, a move that could alienate consumers. Many economists are watching out for higher prices on imported goods in coming months.

But their impact is wide-ranging. For bankers, payments networks and FinTech platforms, the era of tariffs affects trade‑finance credit, supply‑chain hedging and working‑capital automation. Product heads must now address new calculations for budgeting capital, currency exposure and re-routing suppliers, functions that tap into fee‑generating services, from letters of credit to cross‑border virtual accounts to receivables‑backed deals.

The tariff era also affects how card issuers and digital wallets price cross‑border commerce. If duties are here to stay, merchants will front‑load them into sticker prices rather than spring surprise “tariff surcharges” at checkout. That may force acquirers and payment platforms to revisit their fraud models and interchange.