Joe Wicks and Dr Chris Van Tulleken, creating the world’s most harmful protein bar in Channel 4’s Licensed to Kill last month, made headlines. The sweeteners, goo, flavouring and other industrially produced edible substances they poured into an innocent-looking and apparently extremely tasty fake chocolate bar, have been linked to diarrhoea, other gut issues, an increased risk of stroke, cancer, and what Van Tulleken describes with alarming confidence as “early death”.

A nation trembled. But who should have been trembling in a very specific way? Generation X. Snagged silently between the gobby social media hoggers of baby boomers and millennials, those of us who’d been paying attention to US medical journals (a very specific subset, admittedly) will have seen just one week previously a paper from the University of Michigan, which has discovered that this is all affected Gen X’s health has suffered in a very unique way.

It’s only the second piece of research in the US looking at the intersection between older age groups and ultra-processed food (UPF), and it points out that Generation X were the first generation to have UPF feature heavily in their diets from an early age. The results are clear. Twenty-one per cent of women and 10 per cent of men in Generation X meet criteria for addiction to UPFs, outweighing other addictions like alcoholism (1.5 per cent) and smoking (4 per cent ).

The term “ultra-processed foods”, just in case you’ve not come across it, was defined by the Nova food classification system, developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo, Brazil. It defines food in four categories depending on what’s been done to it during its production.

Unprocessed or minimally processed foods include fruit, vegetables, milk, fish, eggs and other foods with no added ingredients. Processed ingredients include salt, sugar and oils used to cook with. Processed foods combining groups one and two in a way you could do at home, like jam, pickles, tinned fruit and vegetables. Ultra-processed foods, however, have more than one ingredient that you’d never find in a kitchen, such as chemical-based preservatives, emulsifiers, sweeteners, artificial colours and flavours.

But that’s only half the story. It doesn’t explain why those Gen Xers got addicted, showing strong cravings, repeated unsuccessful attempts to cut down and withdrawal symptoms. It also doesn’t explain why some of this cohort say they even sometimes avoid social situations because of fear of overeating. Or why they over-index as UPF addicts who are overweight and are isolated and have poor mental health.

Boomers, by the way, not so much. Just 12 per cent of women and 4 per cent of men from the golden generation count as UPF addicts. In case the cheap housing, large pensions and jobs for life weren’t enough of a reward for being born in the 1950s and early 60s, they’d also been taught to cook from scratch – a habit many of them never abandoned.

“Generation X was the first to grow up surrounded by ultra-processed foods,” Dr Karen Mann, medical director for the digital health app Noom. “If you were a child in the 1970s or 1980s like I was, you probably remember being bombarded with ads for brightly packaged snacks, fast food, and “convenience” meals.

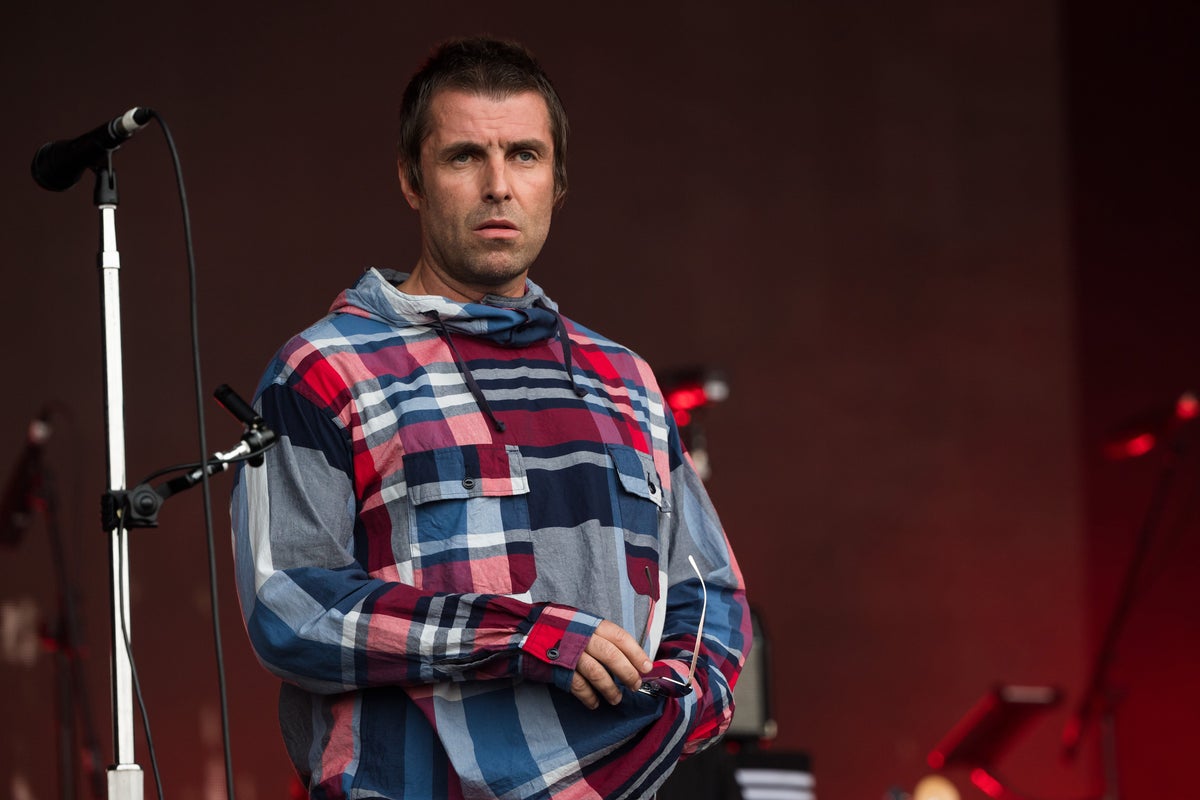

open image in gallery

Pop-Tarts, a staple in the 1970s (Getty)

“Those foods weren’t just available, they were marketed as normal, fun, and family-friendly. In a sense, Gen X was the first test case for how a diet dominated by engineered, hyperpalatable products affects long-term eating behaviour. And being young when UPF arrived shaped Generation X’s tastes and habits early on, making those foods more difficult to resist later in life.”

This was also a generation when both parents started to work too and a more educated population meant many moved away from extended family as they sought out new work opportunities.

“It created a latchkey generation, with parents leaving us food things like French bread pizzas, Findus Crispy Pancakes and Pop-Tarts to snack on when we got home from school,” adds Rob Hobson, nutritionist and author of Unprocess Your Family Life. “Our teeth have suffered, we have a mouthful of fillings, our diets suffered and now we’re reaching midlife, we have high rates of metabolic issues – weight gain, cardiovascular risk, all that kind of stuff.”

As a card-carrying member of Gen X, I look back on Findus Crispy Pancakes, Vesta Curries, Alphabetty Spaghetti, Mr Kipling Cakes, Dalepak Steaks and Bird’s Eye Potato Waffles with genuine affection. There were no health warnings for us. We were just told that Mr Kipling baked exceedingly good cakes, Bird’s Eye Potato Waffles were waffley versatile and Angel Delight was not only delicious, it was also delovely, right?

Our teeth have suffered, we have a mouthful of fillings, our diets suffered and now we’re reaching midlife, we have high rates of metabolic issues – weight gain, cardiovascular risk, all that kind of stuff

Rob Hobson, nutritionist and author

Ironically, UPF’s high calorie content and semi-industrial structure – which makes it faster to eat and faster to digest – is thanks to the American biologist Paul Ehrlich who, in 1968, predicted that the US would face widespread famines in the 1980s, with millions dying of starvation.

He wrote the then seminal Population Bomb, a grim but entirely incorrect book that saw the post-war surge in the population as unsustainable. There were so many of you, they thought we’d all starve. Instead, between 1980 and 1998, we saw the emergence of Big Food to feed us all and obesity rates treble.

open image in gallery

Alphabet spaghetti in tomato sauce (Getty)

“That famine fear gave huge financial incentives for greater food energy creation and technological advances that lead to nutrient poor industrial food products dense in calories per bite, high in too much saturated fat, high in too much added sugar, high in too much salt, far too low in fibre but very cheap,” explains Sam Dicken, research fellow at the Centre for Obesity Research at UCL

“There were tobacco companies getting into food production, using their marketing tricks and product innovations. It was really hard to avoid. We didn’t even have nutritional standards for food until the 1990s. It was an unregulated market.”

Which, of course, was tragic for a generation of kids being brought up on this stuff in the Seventies and Eighties, and then came a cunning switcheroo, which would make things even worse. Having pumped us full of calories, UPF food companies then sold us diet foods like Diet Coke, low-fat or fat-free versions of cereals, yogurts and non-butter spreads – with sugar replaced by aspartame, which can create sugar cravings and fat replaced with sugar.

This, the University of Michigan research suggests, may account for women’s higher addiction to UPF. “One explanation may be the aggressive marketing of ‘diet’ ultra-processed food to women in the 1980s,” according to Ashley Gearhardt, professor of psychology at the university.

open image in gallery

Kate Moss, part of Generation X, would have been exposed to the likes of Angel Delight, Findus Crispy Pancakes and Pop-Tarts (Getty)

“Low-fat cookies, microwaveable meals and other carbohydrate-heavy products were sold as health foods, which can be especially problematic for those trying to reduce the number of calories they consume. Their engineered nutrient profiles may reinforce addictive eating patterns. This especially affects women, because of the societal pressure around weight.”

And to add a cultural smack in the face to the UPF injury, as poor old Gen X staggered uncertainly into the 1990s and faced a wave of insane fad diets like the detox diet (consume only water or juice); the cabbage soup diet (seven days on just low calorie cabbage soup); the food combining diet (don’t eat certain foods in the same meal because they digest at different rates) and the Atkins diet (eat as much protein and fat as you like but no carbs).

My friends tried most of these. “I nearly attacked my flatmate for eating toast while I was detoxing, it smelt so good,” one recalls, “While on the cabbage soup diet, I actually passed out using the treadmill at the gym.” Another says; “Honestly, I think I tried everything that came along. They made me angry and so hungry I’d break and just stuff my face. It was the 1990s, so I had unhealthy relationships with everything – pills, coke, food, diets and booze. Weirdly, I look back on it as a fun decade. I guess that’s because the Cold War was over and the War on Terror hadn’t arrived. The only person working hard to kill me was me.”

Caroline Buck, a health psychologist, and Dr Abigail Fisher, professor of physical activity and health, work at the Centre for Obesity Research with Sam Dicken. They’re trying to wean healthcare workers off UPF, telling me: “They’re at high risk down to shift work and lots of UPF available in hospitals,” Buck explains. “But we found that the whole diet culture is an older age thing that we just didn’t see with younger participants in our study. They had a very different mentality.”

open image in gallery

Pizza on a baguette (Getty)

For all age groups, they found that a combination of regular one-to-one online video calls, monthly support groups, setting goals, having them self-monitor, providing booklets and a website with information… It was a lot, all based on something called a behaviour change wheel, which is way more complicated than cabbage soup. And it’s taken six months so far. This is the power of UPF – it’s addictive, but it’s everywhere, and it still makes up 60 per cent of the average UK diet despite people being more aware of it than ever.

No wonder, Mounjaro and Ozempic are so popular among Gen X’s in the UK. Private-market data for Mounjaro indicate that “people aged 40-59 make up over half of Mounjaro users, and the average user age was reported as 50.2 years. And older users are also more likely to use it for chronic conditions (diabetes, heart disease) rather than solely for slimming, too.

It makes me feel a little bad about how little we noticed back in the 1980s. There’s plenty of work done on adolescents, but only now are we really understanding how the early diets of those in their fifties today have impacted their health. Gen X came home from school alone, put the UPF into the microwave and chowed down alone, and then were left to wrestle with the twisted diet culture, which came for them as they hit their twenties.

No wonder they call us the forgotten generation. Perhaps it’s time to remind people we’re here, because, if we don’t, the cost of ignoring the mounting health crisis coming down the track will.