(© cliplab.pro – stock.adobe.com)

In A Nutshell

Darker morning urine was linked to stronger cortisol responses during stress.

Low fluid intake (about 1.3 L/day) showed higher stress reactivity than high intake (4.4 L/day).

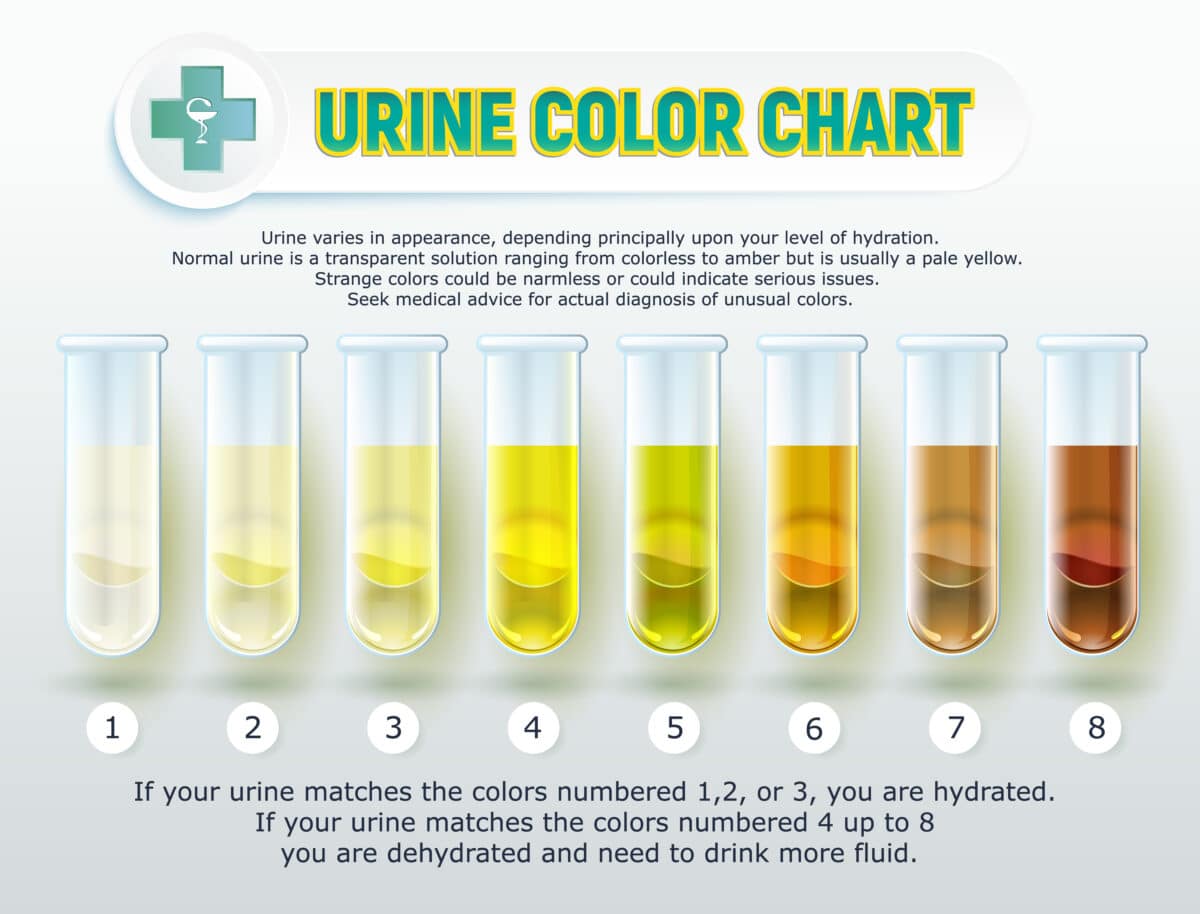

Urine color of 4 or above on the 8-point chart signaled greater cortisol reactivity.

Hydration may help support stress resilience, though more research is needed.

LIVERPOOL, England — A quick glance at the color of your urine after you wake up could reveal more about your day than you realize. New research from Liverpool John Moores University shows that individuals with darker and more concentrated urine in the morning exhibit stronger stress hormone responses when facing challenging situations.

Adults whose morning urine appeared darker yellow had stronger cortisol responses to psychological stress compared to those with a pale, diluted urine color. Researchers could identify a strong association between urine color and stress hormone reactivity using controlled laboratory analysis with a standard 8-point chart.

The discovery emerged from a controlled experiment involving 32 healthy adults aged 18-35. Each person underwent the same stressful laboratory test: a simulated job interview with public speaking and mental math performed in front of judges. While everyone reported feeling equally anxious during the ordeal, their cortisol levels told a different story.

The Link Between Stress And Urine Color In The Morning

Participants with morning urine scoring 4 or higher on the color chart (indicating dehydration) showed sustained cortisol elevation for 30 minutes after stress testing. Those with lighter urine colors did not show statistically significant cortisol increases to the same stressful experience.

The connection between urine color and stress hormone response showed a strong correlation, with researchers identifying a robust association between morning hydration assessments and cortisol reactivity.

Darker urine signals that the kidneys are concentrating waste products to conserve water, indicating suboptimal hydration. When the body operates in this water-conservation mode, it becomes linked with stronger stress responses.

Your urine color in the morning might hint how you’ll feel that day. (Photo by Richard Pinder on Shutterstock)

How Water Shortage Amplifies Your Stress Response

The biological explanation centers on interconnected pathways between water regulation and stress response systems. When fluid levels drop, the body releases arginine vasopressin (AVP) to retain water. This same hormone triggers the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which controls cortisol release during stress.

People who routinely drink less water showed patterns linked to higher stress system activity. Low fluid intake was associated with higher AVP activity, which can amplify cortisol release during stressful situations.

Researchers recruited participants based on their existing fluid intake patterns: those consuming very little daily (about 1.3 liters) and those with much higher consumption (4.4 liters daily). The low-fluid group consistently showed darker urine colors and higher stress reactivity, while well-hydrated participants maintained both pale urine and blunted cortisol responses.

Practical Stress Protection

For most adults, these results point toward a straightforward morning assessment that could predict daily stress resilience. The urine color chart used in the study ranges from 1 (very pale yellow) to 8 (dark amber). Colors of 3 or below typically indicate good hydration, while 4 and above suggest the body needs more fluids.

(Image by Sergey Shenderovsky on Shutterstock)

Many adults routinely consume less than the recommended daily water intake. Health organizations suggest about 2.5 liters for men and 2 liters for women from all sources including food, yet surveys show large portions of the population fall short.

Laboratory stress testing used in the study involved impromptu speeches and mental arithmetic under observation, mirroring many real-world scenarios people face. Job interviews, presentations, difficult conversations, and performance evaluations all trigger similar physiological responses.

Both hydrated and dehydrated participants reported identical anxiety levels and showed similar heart rate increases during testing. The key difference appeared in their hormonal responses, suggesting hydration status affects how the body processes stress internally rather than changing perceived stress levels.

Long-Term Health Consequences

Cortisol serves important functions during acute stress, helping mobilize energy and focus attention. However, consistently exaggerated responses can contribute to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, immune dysfunction, and metabolic problems over time.

Previous epidemiological studies have linked chronic low fluid intake with increased risks of kidney disease, heart problems, and diabetes. If poor hydration leads to amplified cortisol responses to daily stressors, this may help explain some associations seen in larger population studies.

Researchers noted that most studies examining stress and health outcomes haven’t considered participants’ hydration status, potentially missing a significant factor. Their work suggests that hydration might serve as a simple, modifiable buffer against the physiological toll of daily stress.

While the current study used laboratory-induced stress, the biological mechanisms likely apply to everyday situations. People maintaining better hydration through consistent fluid intake may experience less intense hormonal responses to work pressure, relationship conflicts, financial concerns, and other common stressors.

A Simple Daily Assessment

Urine color provides a practical way to gauge both hydration status and potential stress reactivity, though it should not be considered a medical diagnostic tool. Unlike blood tests or sophisticated measurements, this assessment can be done at home, keeping in mind that color can be affected by certain foods, vitamins, medications, and medical conditions. B-complex vitamins, for example, often create bright yellow urine regardless of hydration status.

Morning urine color provides the most reliable reading since it reflects overnight concentration patterns. People consistently showing colors of 4 or higher might benefit from increasing their daily fluid intake, potentially improving both their hydration status and stress resilience.

Research shows that hydration status may influence more than just physical comfort or kidney function. It appears to affect basic aspects of how our bodies respond to psychological challenges, potentially affecting everything from work performance to relationship dynamics.

“Cortisol is the body’s primary stress hormone and exaggerated cortisol reactivity to stress is associated with an increased risk of heart disease, diabetes and depression,” said study lead author Neil Walsh, a physiologist at Liverpool John Moores University, in a statement. “If you know you have a looming deadline or a speech to make, keeping a water bottle close could be a good habit with potential benefits for your long-term health.”

For people seeking better stress management, looking at your urine color in the morning might offer both an early warning system and a simple intervention target. Maintaining adequate hydration could serve as basic support for other stress management techniques, creating a more resilient physiological baseline for handling life’s inevitable pressures.

Disclaimer: This article is for general information only and is not a substitute for medical advice. For personal guidance on hydration or stress management, consult a qualified health professional.

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers recruited 32 healthy adults aged 18-35 and screened them based on their habitual fluid intake using validated questionnaires and week-long fluid intake monitoring. They identified 16 people with low fluid intake (averaging 1.3 L/day) and 16 with high intake (4.4 L/day). Participants maintained their usual drinking habits for seven days while researchers monitored their hydration status through urine samples. On day eight, each person underwent the Trier Social Stress Test, a standardized laboratory stress procedure involving public speaking and mental arithmetic. Researchers collected saliva samples at multiple time points to measure cortisol levels and assessed anxiety and heart rate responses throughout the testing.

Results

Both groups showed similar increases in anxiety and heart rate during stress testing, but cortisol responses differed significantly. The low fluid intake group showed meaningful cortisol increases lasting 30 minutes after stress testing, while the high fluid intake group showed no statistically significant cortisol changes. Low fluid intake participants had higher peak cortisol responses compared to well-hydrated participants. Hydration status, measured through urine concentration, strongly predicted the magnitude of cortisol response to stress. Participants with darker, more concentrated urine on the morning of testing showed greater cortisol reactivity regardless of their fluid intake group.

Limitations

The study used a cross-sectional design, so it cannot establish whether low fluid intake causes higher stress responses or whether the relationship works differently. The laboratory stress test, while well-validated, may not reflect real-world stress experiences. Researchers excluded people with moderate fluid intake, focusing only on the lowest and highest quartiles, which may limit generalizability. The study included relatively few participants and lasted only eight days of monitoring. The research also couldn’t determine long-term health consequences of the observed differences in stress hormone responses.

Funding and Disclosures

Liverpool John Moores University received funding from Danone Research & Innovation to cover salary costs for two researchers and data collection expenses. Several co-authors are current or former employees of Danone Research & Innovation, though the principal investigator received no personal compensation. One co-author works for ATLANSTAT on behalf of Danone Research & Innovation.

Publication Information

This research was published in the Journal of Applied Physiology, Volume 139, pages 698-708, September 3, 2025. The study was registered as a clinical trial (NCT05491122) and received local ethical approval. The work was conducted at Liverpool John Moores University’s Faculty of Health, Innovation, Technology and Science in collaboration with Danone Research & Innovation in France.