One-third of people older than 85 in the United States are estimated to live with Alzheimer’s disease today, according to the National Institute on Aging. The condition’s characteristic long, slow decline places an enormous burden on families and on society. While the need for new treatments is urgent, Alzheimer’s is a complex disease that requires multidisciplinary research across a wide range of specialties.

In a new article led by Yale’s Amy Arnsten, researchers from across numerous disciplines share an update on the varied efforts that are driving these new treatments.

Writing in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, the group of experts – whose fields span neuropathology, fluid biomarkers, PET imaging, and proteomics/transcriptomics, as well as basic research – focus specifically on the early stages of the disease when new preventive therapies may be most effective.

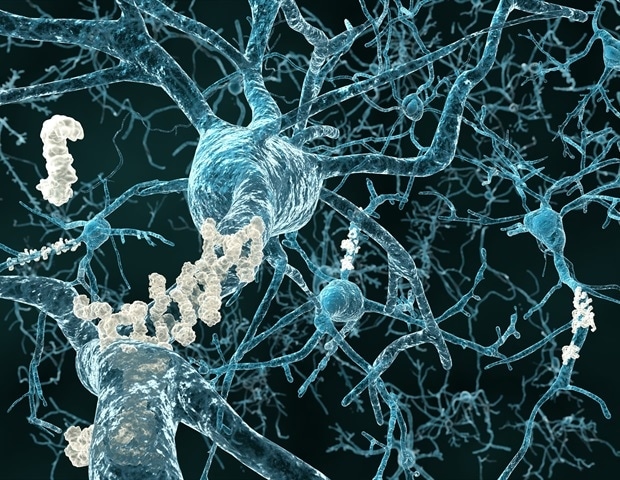

This integrated view highlights that Alzheimer’s pathology can be initiated by many different factors, including protein buildups in the brain and inflammation that appear to drive neurodegeneration in the common, late-onset form of the disease, said Arnsten, the Albert E. Kent Professor of Neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine (YSM) and professor of psychology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

“We’re at a tipping point in Alzheimer’s research today where we have begun to have the first treatments for the disease, but we still have a long way to go,” Arnsten said. “We need to keep pushing ahead to have more effective medications with fewer side effects.”

In an interview, Arnsten explains why so many more people are expected to develop Alzheimer’s in the coming decades, the opportunities for new treatments, and challenges that threaten to halt this progress.

In addition to Arnsten, the Albert E. Kent Professor of Neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine (YSM) and professor of psychology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, contributors include Christopher H. van Dyck, the Elizabeth Mears and House Jameson Professor of Psychiatry and of neurology and neuroscience at YSM, Dibyadeep Datta, assistant professor of psychiatry and of neuroscience at YSM, as well as Heiko Braak and Kelly Del Tredici from the University of Ulm in Germany; Nicolas Barthelemy from Washington University in St Louis; and Edward Lein and Mariano Gabitto from the Allen Institute for Brain Sciences and the University of Washington.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the state of Alzheimer’s disease research today?

Amy Arnsten: Alzheimer’s research has expanded tremendously over the last decade, and we are now at an extraordinary time. After decades of research, the lessons we’ve learned about the brain changes that cause the disease are beginning to translate into FDA-approved treatments.

There are currently two approved antibody treatments that remove beta amyloid, one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, from the brain, and slow the course of the disease. But they don’t stop it, and they don’t work for everyone. They can also have some pretty serious side effects.

Why is dementia so prevalent now?

Arnsten: Aging is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, and people are living so much longer, especially now with many effective treatments for diseases like cancer. Aging is also a risk factor for other causes of dementia, such as vascular dementia, and dementia related to Parkinson’s disease. Sometimes the forms overlap, which is particularly confusing for neuropathologists. These diseases place an enormous burden on patients and on their families.

What is new research focusing on?

Arnsten: There are many new approaches in the pipeline. Early intervention is one big priority. We need effective treatments with benign side effects so we can catch the disease early – maybe even before people start showing symptoms – and slow it down. My lab is researching the toxic actions caused by inflammation that contribute to Alzheimer’s. The goal would be to have a treatment you could use very early – once the test indicates risk even if the patient has no symptoms – that is also remarkably safe. You want to be able to use this with a patient who is, say, 50 years old, because the process can start when you’re still young.

Why does it take so long for discoveries in the lab to become medications people can take?

Arnsten: In many ways, Alzheimer’s researchers have had to invent the field, and innovations from disciplines such as genetics, cell biology, neuroscience, spectroscopy, and brain imaging have all been necessary to figure out what was changing in the brain and why. There appear to be multiple drivers of brain pathology, for example, where inflammation may contribute greater risk in some people than in others, which makes things more complex. But it also offers more opportunities for different kinds of treatments.

This type of translational science is necessarily slow, as it takes time to unravel the many factors that initiate and drive the pathology. And once you have discerned a possible therapeutic target, it takes great time and expense to determine that a treatment is effective and safe in patients.

What are some of the more notable new breakthroughs in the field?

Arnsten: One key recent breakthrough is a new blood biomarker that can detect the beginnings of tau pathology [accumulation of the tau protein in the brain], which is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. This signal of emerging pathology in the brain can be seen long before one can use PET imaging to see later stage tau pathology in the brain. This new blood biomarker will also allow us to track whether a new treatment is working.

There are many new, and likely better, treatment strategies also in early stages of testing that will likely not come to fruition if Congress cuts the NIH [National Institutes of Health] budget. This would be a tragedy for so many patients and their families, and would also be very short-sighted, as the financial burden of caring for patients by the federal government is enormous.

In my lab, we’ve worked for 20 years to understand some of the early changes that especially afflict the neurons that generate memory and higher cognition, and we have identified a compound that we think can stop these early, toxic effects of inflammation with few side effects. But now, due to NIH budget cuts, we can’t get the funding to continue. These cuts will be devastating to so much research, and the field can’t just bounce back from them, because they will destroy so much of the research pipeline, hurting our health and also the U.S. economy. In the past, Congress understood the importance of NIH-funded research to American strength; we hope that rational strategies can still prevail.

Source:

Journal reference:

Arnsten, A. F. T., et al. (2025). An integrated view of the relationships between amyloid, tau, and inflammatory pathophysiology in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer S & Dementia. doi.org/10.1002/alz.70404.