Experts At The Table: AI/ML are driving a steep ramp in neural processing unit (NPU) design activity for everything from data centers to edge devices such as PCs and smartphones. Semiconductor Engineering sat down with Jason Lawley, director of product marketing, AI IP at Cadence; Sharad Chole, chief scientist and co-founder at Expedera; Steve Roddy, chief marketing officer at Quadric; Steven Woo, fellow and distinguished inventor at Rambus; Russell Klein, program director for the High-Level Synthesis Division at Siemens EDA; and Gordon Cooper, principal product manager at Synopsys. What follows are excerpts of that discussion. To read part one of this discussion, click here.

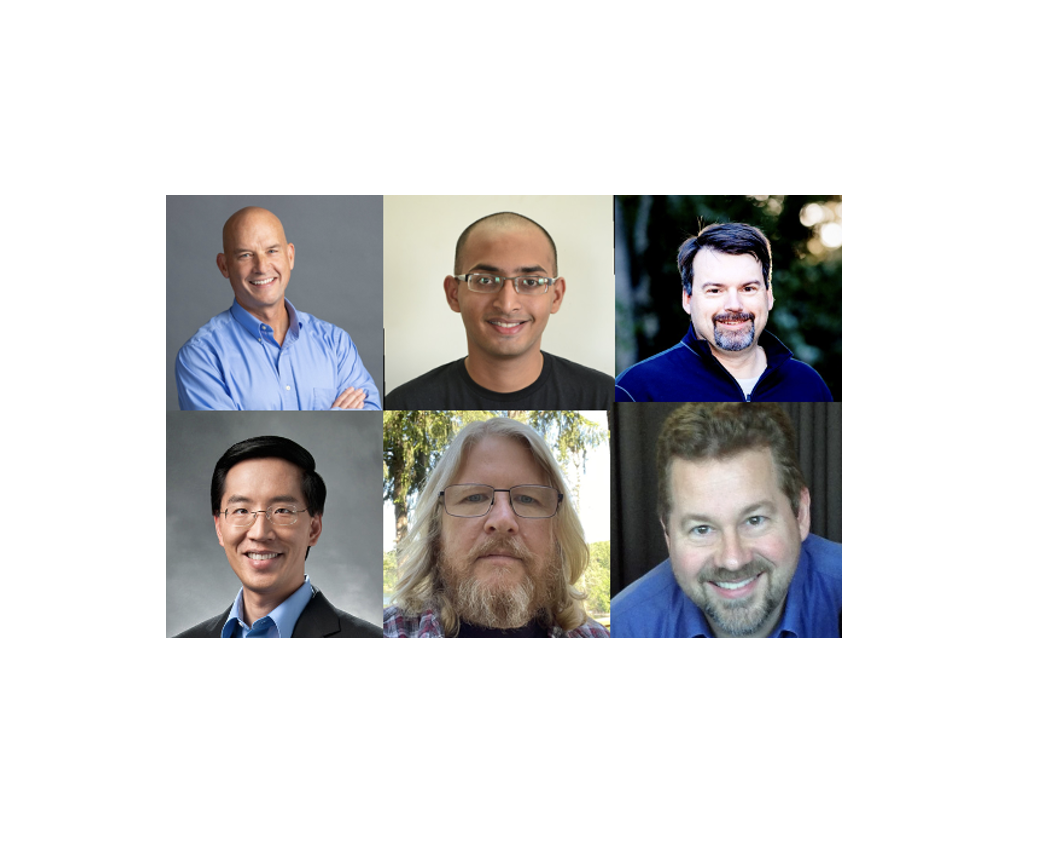

L-R: Cadence’s Lawley, Expedera’s Chole, Quadric’s Roddy, Rambus’ Woo, Siemens EDA’s Klein, and Synopsys’ Cooper.

SE: What are some of the tradeoffs around NPUs?

Cooper: I’ll offer one from the CNN days. You want to trade off area efficiency in as small an area as possible, while also ensuring future-proofing and flexibility. For example, there are activation functions, ReLU, PReLU, Swish, whatever you could design, one at a time, and hard-wire that in. And if there’s only two, three, four, or five, you can do that. But then you don’t know what’s coming out. You don’t know what the next paper will have. So now you have to do the tradeoff and say, ‘Maybe I need to create a lookup table, which is more expensive in area than one or two, but in the long run it pays off because now I can do any activation function.’ It’s these tradeoffs you need to figure out. When do I have to make a flexible engine, and when can I hard-code it, because I’m guessing that it’s not more flexible that way? And unfortunately, it’s rare that you can hard-code something and really optimize it like an ASIC, because you don’t know what the next algorithm will require. You need some level of flexibility.

Roddy: Gordon really nails it on the hardwired versus programmable tradeoff. With the design time for a complex SoC stretching 24 to 36 months, but with state-of-the-art (SOTA) AI models changing monthly, designers are faced with a daunting task of locking down a silicon architecture today that will likely need to run an unknown future workload in 3 years. Architects need to huddle closely with their product planning teams to decide, ‘Can we really be certain the workload won’t change much,’ before committing to inflexible, non-programmable solutions. For some select subset of designs – closed boxes that won’t need new algorithms – a fixed-function AI accelerator works. But a large majority of designs that we’ve encountered clearly want a general-purpose programmable NPU.

Chole: In automotive deployments, when we are looking at actual workloads, multiple requests come in, and the cadence of the request or the latency requirement is very different. Some requests have extremely deterministic guarantee requirements. Basically, if you get a request, you must respond within 10 milliseconds. Otherwise, the system cannot really function. You must give those ASIL guarantees. In such scenarios, there is a system-level tradeoff that you need to do concerning how you are designing your runtime and how these multiple applications need to interact with each other. How can you context-switch an application completely, where you have to tell NPUs to stop running ‘this’ and start running ‘that?’ You have to save the state, load the state again. And there’s a question of priorities. There is a question of getting the determinism out of the system, because we guarantee that NPU is deterministic by itself. But as a system, to be able to give that guarantee, the bandwidth needs to be deterministic — or the allocated bandwidth needs to be deterministic to the NPUs, and the runtime also needs to be able to support that jobs can be swapped on the fly. I can make the tradeoff, and I can keep the entire SoC busy, not just the NPU. I can maybe keep the GPU part busy. The pipeline is always going on, so different application domains create different and interesting tradeoff questions. Automotive is going toward server class. Even such features as isolation guarantees that divide the NPU into multiple parts with virtualization are coming into automotive deployments.

Klein: One of the hard tradeoffs is how programmable to make this versus how much performance and efficiency we want to get. In the high-level synthesis world, I’m often working with customers who are deploying a very specific implementation in ASIC or FPGA, and we can often very significantly outperform a GPU or an NPU. But we’re putting so much into a hard-coded implementation that it’s no longer future-proof. There are applications where it’s fine to nail down parts of the architecture, where we know for our typical embedded applications, not a data center, that we’re always going to be doing these things. We know we’re going to be pre-filtering some video data coming in, and it’s always going to look like this. Well, we can put that into hardware, into ASIC or FPGA logic, and dramatically improve the performance and power characteristics, but there’s no going back if we want to. If we want to change that later on, we’ve got to build a new chip, or with an FPGA, go reprogram.

Lawley: Programmability and flexibility can mean a lot of things. In some cases, that may mean, how do you future-proof things like activation functions? In other cases, that may mean how much scalar and vector compute is added for the matrix compute allocation of the NPU. If you have too much scalar and vector compute, you have wasted area. On the other hand, if you don’t have enough scalar and vector compute, that can lead to excessive fallback or bottlenecks in the architecture, degrading performance. And then there is the flexibility of the number of MACs, the size of dedicated memory, and the interface bandwidth, just to name a few. We try to give the customer the flexibility they need to make the decisions to right-size the IP, and then we make the decisions that are more nuanced and difficult to make without understanding the architecture of the NPU.

SE: For that reprogramming, do you mean embedded FPGA, or a type of interposer, MCM, or something else?

Klein: All of the above. Embedded FPGA is particularly good because it eliminates the chip-to-chip problems, and you can get much more bandwidth and faster transfers using less power. So certainly, if we can put FPGA fabric next to our other compute units, that’s an ideal situation. But if you’ve got a lot of data reuse, using a discrete FPGA can be a viable solution.

Cooper: I agree. Certainly, it’s very use-case dependent. If you’re deeply embedded, you have a handful of graphs or models that you want to implement. That’s a great way to go. On the other hand, maybe you’re going to have 100 different people programming this, and you don’t know what models you are going to bring to it, and that has to be much more flexible. It really depends on the use case.

Woo: Here’s an example of a tradeoff that we sometimes see is at the high end. With some of these processors, where they’re spending 50% of their power budget on the PHYs and things that just move data back and forth, either to memory or chip to chip, you really have to be careful and decide whether to take those watts and spend them on moving data in and out, or do you want to possibly remove some of the external bandwidth capability and spend the watts on more compute. Then you’ve got to figure out how to keep this in balance, like Russ is mentioning, and that’s what these architectures are about. It means you have to think about, ‘Do I quantize? Do I go to different algorithms?’ Some of the tradeoffs we see are because of what we do. We see them more on the physical side, and it may mean picking a different kind of memory, or changing the way you architect the rest of the SoC, where those interconnects are outside of the chip. You’ve got so many watts, and you know there’s some fraction you want to spend on the compute, because there’s a performance level you need to get to. It’s often the case that you just can’t give them enough bandwidth. They’re either power-limited or there are not enough pins, for example, on the processor. So you give them what fits within their budget. And even that, in many cases, is not enough or not what they really want. When they’re faced with this decision of how many cores they can really put down, and how accurate the computation needs to be in each of those cores, you can go to things like more quantized representations, or fewer bits per parameter, and that extends the effective bandwidth for what you’re trying to do. But then that can be an accuracy tradeoff. So there’s this challenging thing from the physical side of it, where you are limited by what you can do on the chip, and you have to think very carefully about how many watts you really want to spend moving data in and out. Then, what’s the best way to represent the data to use those watts? What’s the best core implementation that uses the remaining watts, so everything stays in balance?

Cooper: The amount of internal SRAM you have on the chip is flexible. The more you have, the less external data movement you need, and therefore less power consumption on those external pins. That helps you and helps you with performance, but it kills you in area. So power, performance, and area are all tradeoffs and degrees of freedom. You don’t have unlimited area, but there’s flexibility there, and you have to decide which way your specific design needs to accommodate that tradeoff.

SE: These are all extremely nuanced tradeoffs to make. When you look out at your customers and the activity that they’re doing, what is the level of expertise needed to make these tradeoffs? Are we training the lower-level engineers to come up to speed on this, because these are issues that are only going to get more challenging?

Cooper: There’s certainly a learning curve. The first time out, you’re probably going to make some mistakes that you didn’t realize. As you iterate, there’s some level of learning from your mistakes. The problem is that those mistakes, as you go from 5nm to 3nm to the smaller design nodes, become more expensive, so you can’t afford to make them. Therefore, you need other tools to offset and pre-test, like digital twins, etc. There is that level of learning.

Chole: As we are working with customers, it’s very much a collaboration of 100 different people. It’s a collaboration between the customer’s data science team, the customer’s deployment team, and the software team, which actually has to ingest the models, and this collaboration doesn’t end at tape out. This is a continuous, ongoing collaboration. Then, on the NPU design side, we have architecture, we have hardware instructions, an ISA of that architecture, the hardware team building it, and the compiler team that is building the compiler for it. It’s a very complex problem. Given what we are doing, it’s amazing that we are able to do this, and so far away from the training. When somebody is training the model, they are not really thinking of edge deployments. There are user cases later on that optimize for edge deployment, like shrinking the model down, distillation, and the like. But the basic training that is pushing the boundaries right now is pretty much focused on the data center. The challenge is how to take that, how to shrink it down, how to make it fit for the accuracy as well as power, area, and the cost budget that we have, then going to the final deployment and actually running it. It might be running live. It might be doing 60 frames per second. That’s an amazing feat, and it is a huge collaboration. Is anybody coming up to that speed, that level? Even I’m not there, if you say, ‘Hey, guide these 100 people together,’ I don’t have that expertise. I need somebody to do the data science. I need somebody to do the physical design. I can’t do that by myself. It’s a collaboration.

Klein: What we’re doing is combining some different domains of knowledge and engineering. They really need to work together to achieve an optimal outcome. To give an example, we held a hackathon last summer where people were using high-level synthesis to implement an AI accelerator, not really an NPU, but a bespoke accelerator. What was interesting was how the winner was able to create the best implementation. The way we judged the implementation was how much energy was used per inference. We looked at all the entries and figured out which one used the least energy. The guy who created the smallest, most efficient implementation beat my reference implementation. I’ve been using this tool, and he ended up using about half the energy that my example did. The way he did it was to say, ‘You’re not training this thing well. You’ve got to take this network, and change the training,’ and that increased the accuracy. With that increased accuracy, he was able to use fewer multipliers and fewer channels within the layers, but still get the minimum accuracy. He was able to hit that with a smaller design by changing the training and changing the architecture of the network a little bit. It wasn’t just hardware design. It was neural network design, as well, and understanding how to most efficiently train this, create the highest level of accuracy, and then implement that in hardware. It’s a broad range of skills, and this one guy had both the hardware design and the neural network design, and was able to bring those together. And he won the contest. That was kind of fun.

Woo: What I’m noticing is that there is the hardware side of things and the software side of things. The industry has done a great job of making it cheaper and more available to do compute, and you see all these open-source models, lots of classes in universities, and things where you get to use some of these models. Because they’re open source, you can tweak them, and you can learn a lot of the basics about what’s going on. The bigger challenge is on the hardware side and the physical implementation, because it’s become more expensive to produce hardware. If you had asked this question about training engineers in one of the most important areas in semiconductors — advanced packaging — the packaging is really helping us get the physical capabilities that the silicon needs, which is to move data in and out quickly. Those things are tougher, more expensive, and the expertise is harder to acquire. What I see going on is that there is a growing divide in what you’re able to train people to do in college versus what goes on in the more advanced designs these days. This is true on the software side, as well. The hardware side is complicated by the fact that it’s more expensive to produce the hardware. It does seem like there needs to be, if we’re to succeed as an industry, a way to accelerate the training and broaden the training to a larger set of people.

Chole: I come from a software background, with completely zero formal education in hardware. Everything I learned, I learned [at previous companies], a previous startup, and this startup. It’s phenomenally mind-boggling coming from the software world. I cannot ever learn this unless I have access to tools, unless I have access to advanced methodologies. And companies have been building in-house technologies for so long that I don’t even know how an Intel, which might be running at 3.6 gigahertz, does that. I can’t comprehend the complexity they are dealing with. The cost of getting there is so much. At the startup, we can’t really even think about that. The training here is pretty much hands-on. I had to learn from experts in the field to be able to get here.