Opioid receptors are fantastic targets for treating pain—but unfortunately, the drugs that target them can be addictive. Because the molecules suppress breathing and heart function, those drugs can also be deadly. Researchers at the University of South Florida recently announced an advance in pharmacologists’ long-term goal to make a compound that could preserve the pain relief but ditch the undesirable side effects (Nature 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09880-5).

Opioid receptors are a subset of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). These membrane proteins transmit signals into the cell through a dance of proteins coming together and splitting up, powered by binding to guanosine ligands.

When an agonist like morphine or fentanyl binds to a GPCR, the receptor recruits an effector, called a G protein, that binds to guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and triggers downstream effects. Over time, the G protein hydrolyzes GTP, rendering itself inactive.

Matthew Swanson, a graduate student who worked on the new advance, compares the consumption of GTP to a car burning gas. “When you run out of gas, your car dies,” he says.

But for almost a decade, Swanson’s supervisors, USF professors Laura M. Bohn and Edward Stahl, have been developing an argument that GPCRs have another mode of action. In certain active states, a GPCR can recapture a GTP-bound effector—which could create a more renewable activation state. “Instead of us using that gasoline, we would just be running a battery,” Swanson says.

This discussion may all sound like esoteric biochemistry. But because compounds that favor different GPCR active states can alter downstream signaling, the process could enable researchers to develop compounds that can trigger certain effects and skip others. In the case of opioid receptors, the goal is to block pain sensing without suppressing breathing and heart rate.

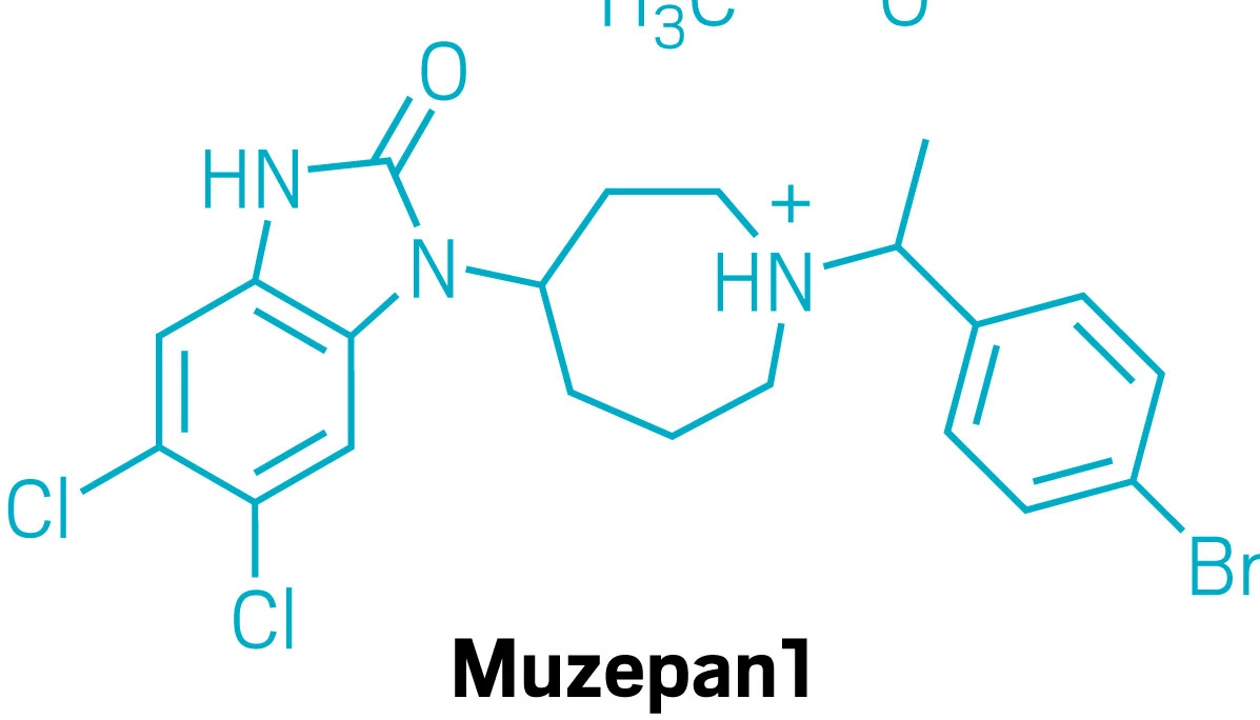

Bohn, Stahl, Swanson, and colleagues say they have found a compound that can separate out those functions because of how it interacts with the mu opioid receptor. The compound, muzepan1, favors the GPCR state that is like running a battery more than other agonists do.

The researchers found that muzepan1 works as a painkiller; it makes mice less sensitive to painful stimuli such as heat. But more importantly, combining muzepan with a more traditional opioid like fentanyl yields a dramatic increase in pain tolerance—without further slowing breathing or heart rate.

Muzepan is not a suitable compound to use as a medicine, and there are some very big unanswered questions about how, exactly, it synergizes with other receptor agonists. According to Joann Trejo, a GPCR pharmacologist at the University of California, San Diego, much more work must be done to understand how this synergistic effect works, but “the data is convincing that a unique interaction between muzepan and fentanyl is in play.”

Trejo calls the researchers’ discovery and dissection of a new mechanism of GPCR signaling “outstanding.”

Bohn and Stahl say they are excited to find that the new mechanism can separate opioids’ effects on pain relief and vital physiological functions. That ability might, eventually, make for less-dangerous pain relief.

Laurel Oldach is a senior editor and life sciences reporter at C&EN.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2025 American Chemical Society