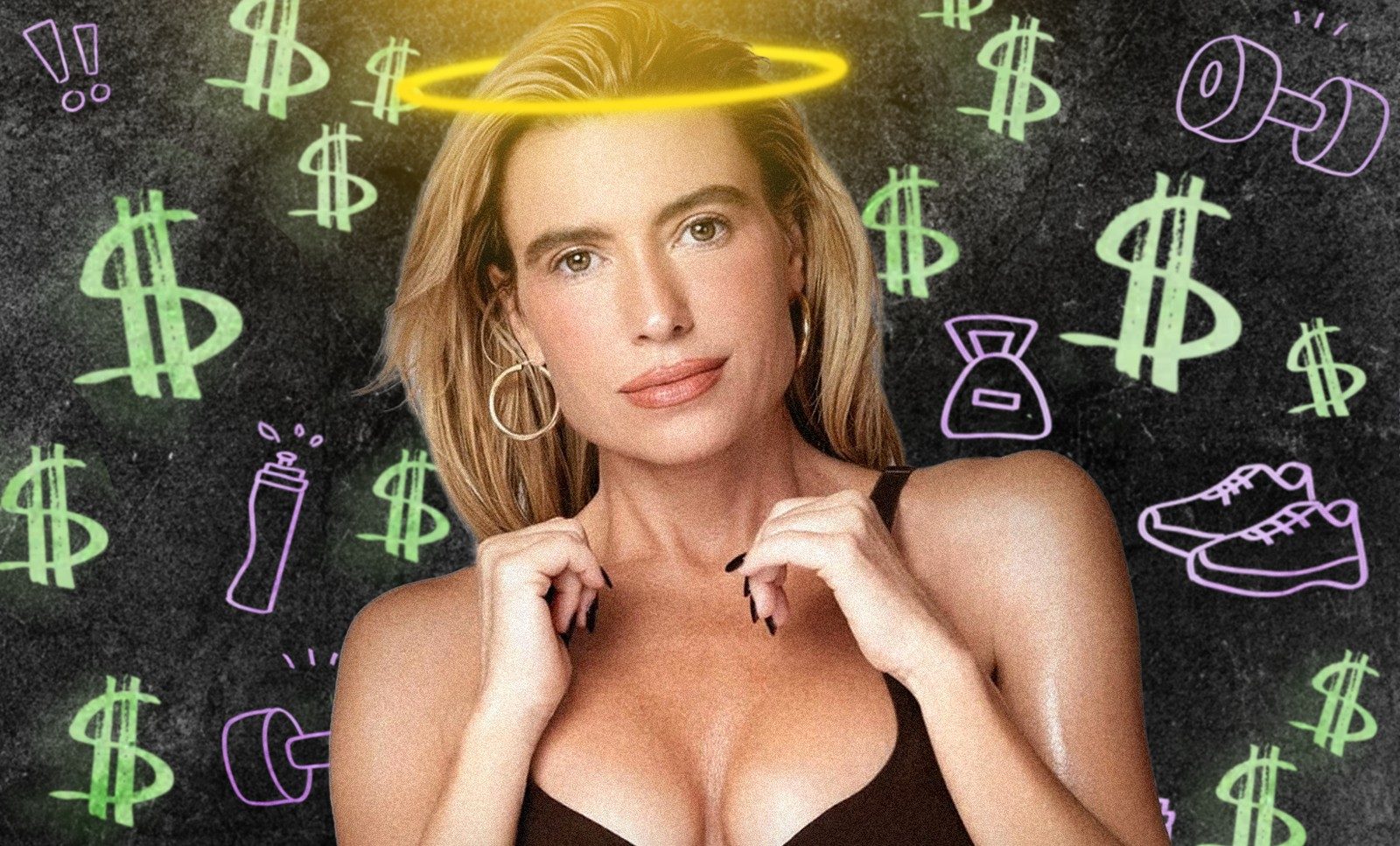

On a recent grey London morning, I arrived at Surrenne, a private members’ gym beneath the lavish Berkeley hotel, that serves as the London studio for Tracy Anderson, fitness luminary and icon of the new (and very old) female beauty standard — think carved, hollow, and busty.

Inside, the air was thick and immaculate, heated to 90 degrees Fahrenheit (“NYC temp,” they told me, “the LA class is even hotter”). The teacher was not Anderson, but a smiling Spanish man named Javi. “No talking,” he said, citing the first rule of Tracy World. “Just music.” We began, and he adopted Anderson’s uncanny-valley grimace. Movements started with small arm pulses, before escalating into kicks and angular twists. To the uninitiated, the signature Anderson method might look something like a jacked-up combination of Pilates and dance, but from within, it is one woman’s unique and vast accomplishment, a sprawling universe of moves (more than 200,000 in Anderson’s library) and routines that comes complete with a creation myth, esoterica, and, of course, merch.

Halfway through, I was drenched. The middle-aged woman beside me, with an enviable six-pack and sparkling gold jewellery, smiled when I asked her after class how long she’d been doing it. “Three months?” she ventured. Javi laughed. “You’ve been here a year!” Time, it turns out, works differently here.

Anderson leads a cult-like empire that frames its offering as more than just a workout. To practice her method is to change your life — it is, as she proclaims, “revolutionary.” Women like me answer her siren call in droves. Hers is the lingo of gentle space, physical truth, creation, purpose, aura, passion, empowerment, and personal transformation. Those of us seeking these things — plus a closer conformity to that beauty standard — have made her $100 million dollars so far, cementing her cultural position with the liberal rich and making her rich-rich in the bargain. Men across the Hamptons wear T-shirts that say ‘MY WIFE IS AT TRACY.’

Online, Anderson reaches far beyond the 1%, connecting to more than a million followers on Instagram. She has a subscription “online studio,” a kind of mini-Netflix of fitness through which you can tune into her live classes or do them on demand. Her p.r. team wouldn’t tell me how many people take her classes — but the more than 15 million on TikTok who have posted videos doing her workouts would indicate the number is high. She first came to fame as Gwyneth Paltrow’s trainer, and offers a similar brand of aspirational wellness as the actress. But Anderson’s has an edge: exercise has become a luxury product, necessary for self-worth and available only to those who can afford it.

The cult of exercise and its promise of personal magnificence are not new. The German-born Joseph Pilates rebelliously invented the choreography that became the global Pilates industry during his internment in England during World War I. About 40 years later, across the world in California, the perverted yogi Bikram Choudhury exported his heated sequence to the West, spawning a proliferation of hot-yoga studios and a culture of sweating it out in sweltering rooms. Both promised their exercise was not just to make you look good — it was to heal you.

With the rise of a new crop of female fitness gurus, the tenor of the promises changed. After escaping the Nazis in Germany, Lotte Berk invented ballet barre and opened a studio in London in 1959, to strengthen, “without adding bulk.” In the 1960s, women — always the target audience of these fitness figures — were gaining sexual and financial freedom, and were discovering that the freedom to do with your body as you pleased meant that the practical activity of losing weight might become a kind of leisure hobby. Huge industries were born. Blond Californian Jacki Sorenson invented “aerobic dance” in the late 1960s, soon to be known everywhere as aerobics. By the 1980s, the “Jane Fonda’s Workout” videos were popularizing the term “feel the burn” and funding Fonda’s political activism by promising women they could “burn off fat” and find “energy for living.”

What’s different about Tracy is not just that she combines the promise of transcendence with weight loss, but that she has harnessed the immensity of the internet to do it. Her rise to stardom coincided with the two great forces: the flourishing of the fitness industry in the 2010s — it grew by 75% mostly driven by women — and the burgeoning world of streaming services. The medium is the message, and Anderson’s message was about to be everywhere. Women, her customers, were getting more money, too. In 2010, women controlled an estimated $5 trillion in the United States. By 2023, that figure had risen to $10 trillion by conservative estimates; McKinsey projects $30 trillion by 2030.

“In Tracy World, the body is both temple and test, a site where moral character is performed through effort.”

With women’s growing financial power came a trap: we would find ever more things to spend money on. This was the era of #GirlBoss capitalism: Dior sold a $700 We Should All Be Feminists T-shirt, and Sheryl Sandberg wanted us to “lean in.” Chelsea Clinton hosted a presidential fundraiser for Hillary at Soul Cycle, where classes run $40 a pop. Exercise studios proliferated.

The high prices and turbo-charged clientele meant that the fitness offerings needed to promise more: it wasn’t just that working out could make you look good or feel good anymore; it was that it could make you be good. Tracy’s waist-trimming DVDs sold in the tens of thousands, and so she set up brick-and-mortar studios, which she could charge even more for. Buying into something was seen as moral participation. To pay was to believe.

Through social media, millions could now see what Tracy did, what she wore, what music she liked or didn’t. Her association with figures like Paltrow, Madonna, and J-Lo, all of whom she’d trained, boosted her own status as a quasi-celebrity. As legend would have it, her fallout with Madonna was so bad no one is allowed to play her music in any TA studio. The fact that people spread such a legend mattered. Watchers formed parasocial relationships with her, enough that when she launched her online studio in 2015, they signed up from all across the world to watch her sweat daily. A subscription allows you not just a workout, but access to the “TAMILY.” And the workouts became an ever-more-expensive commitment. Anderson added “heartstone weights,” and bands, and “premier membership,” and “summer camp.”

In 2020, as the exercise studios were shut down for the pandemic, so were the managerial-class women. Capitalist feminist figures fell down like dominoes: Glossier’s Emily Weiss, Man Repeller’s Leandra Medine, The Wing’s Audrey Gelman, all burned in the flames of cancellation. They had bred “toxic cultures” (an accusation later lobbed at Anderson by various ex-trainers). Fitness studios everywhere were going bust. The rest of us were crawling inside, too, kept away from work or school, slinking reluctantly into domestic confinement. Right where Anderson was waiting for us.

I discovered Anderson in that strange, suspended pandemic time. Anderson streamed daily workout classes from her ranch in Montana, always following her non-speaking rule, but offering comforting platitudes at the end of class about our inner and outer transformation. She told us the best way to spend these wasted days was doing exactly as we were — spending money on her. Her business grew by 120% that year, according to an article in WWD, as the work-from-home world had more time on its hands to move, and to think about how it looked. Consultations for teenage eating disorders increased threefold during the pandemic. Anderson advised we eat fruit puree for breakfast and vegetable puree for lunch.

In the decade leading up to the pandemic, wellness had already slipped its moorings from public health and become a kind of private religion. Anderson’s dialect of health (“detox,” “raw milk,” “natural healing”), once the parlance of liberal hippies and weight-loss aficionados, was consistent with the tenets of what we now know as the MAHA movement, which makes the body, once a source of human frailty, “an object of almost religious devotion,” as Barbara Ehrenreich wrote in her book Natural Causes, published in 2018. In Tracy World, the body is both temple and test, a site where moral character is performed through effort.

Capitalism is the perfect companion for such efforts. In On Immunity, a book on vaccines written years before the pandemic, the critic Eula Biss identifies in the anti-vaccine movement, “evidence of what capitalism is really taking from us.” She argues that it is understandable that such huge swathes of people would feel that the system is up to no good, because in so many other ways they are right. Now, our distrust in systems is being rechannelled into consumption, and the market sells you back the very faith it helped erode.

Anderson knows it well. Last week, she announced a one-day “TracyFest” in Labelle, Fla. She called it an “inaugural rite of realignment festival” for the “global Tracy Anderson” community. The ticket costs $500, not far off the price of a Coachella weekend. The staff that accompanies her workout costs $779. Memberships to her physical studios across America start in the tens of thousands; joining her London studio runs more than $13,400 a year. Small rocks to hold in your hands are $285. You can buy every type of clothing from her, and her new $125 perfume and candle set smells like “sweat.”

When I left Anderson’s studio I felt elated — manic even. I grinned at my fellow travellers on the bus. The world looked beyond beautiful, and the rest of the day felt ridiculously promising. But hours later, I was tired, achy, and fed-up. If I could go to that studio daily, perhaps I’d be able to maintain the euphoria. But who could ever pay that much money, when movement is the one thing the body can do for free? The fantasy of “taking health into your own hands” only works if you have hands free to begin with, if you can pay for the gym, the supplements, the time. The rest are left behind, instructed to “blame themselves” for their sickness. Slumped on the sofa later that night, watching television, my body had returned to itself, untransformed. I told myself I was “fighting capitalism” by refusing to move — and perhaps it was true.